1 June 2020

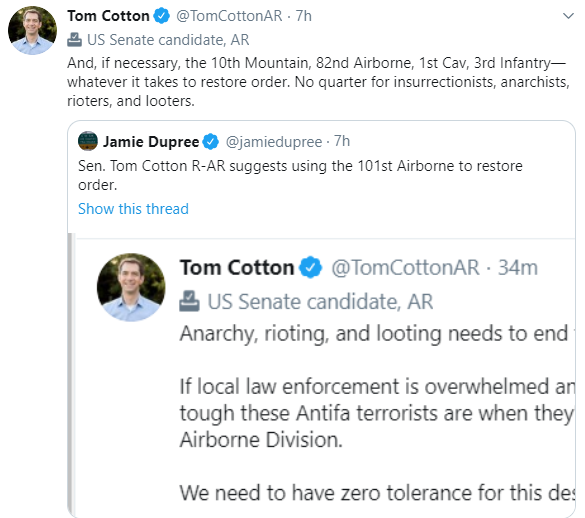

On 1 June 2020, U.S. Senator Tom Cotton, Republican from Arkansas, recommended sending in the U.S. military to quell the riots that had erupted across the nation as a result of the killing of George Floyd by the Minneapolis police. He tweeted that the troops should do:

whatever it takes to restore order. No quarter for insurrectionists, anarchists, rioters, and looters.

When it was pointed out to him that no quarter meant the summary execution of prisoners, Cotton tweeted links to Merriam-Webster and Collins dictionaries. Merriam-Webster defines no quarter as:

No pity or mercy —used to say that an enemy, opponent, etc., is treated in a very harsh way

And Collins defines it thusly:

If you say that someone was given no quarter, you mean that they were not treated kindly by someone who had power or control over them.

And the American Heritage Dictionary, which Cotton did not cite, defines it as:

Mercy or clemency, especially when displayed or given to an enemy

But the situation is more nuanced. There are two operative definitions of quarter, one that is literal and regards the military, and one that is figurative. The Oxford English Dictionary defines the literal sense of quarter as:

Exemption from being immediately put to death granted to a vanquished opponent by the victor in a battle or fight; clemency or mercy shown in sparing the life of a person who surrenders.

Under this definition, an order of no quarter is indeed a horrific crime.

But the OED also outlines a separate, figurative sense. It is this figurative sense that Collins refers to. And Merriam-Webster and American Heritage pack both the literal and figurative senses into one definition.

Now, we can’t get inside Cotton’s head and know what he intended when he tweeted the phrase, but that doesn’t matter. What matters is how the phrase is understood, and it will be understood in the context of the long history of police brutality against people of color. Cotton, intentionally or not, is playing it both ways. He is sending out a dogwhistle of when the looting starts, the shooting starts that has a long, racist history, and then hiding behind the milder, “not treated kindly,” definition when others call him on it.

But this sense of quarter is, to our present-day ears, a rather strange usage. It doesn’t seem related to the sense of one fourth of something or an area or neighborhood. Most uses of quarter in English come from the Anglo-Norman quartier. The sense of military clemency also comes from this French word, but it is a later development, a re-borrowing of the French word during the early modern era. It comes out of the phrase quartier de sauveté, referring to a place of refuge allowed to retreating forces after a battle. So, to say no quarter is to deny the enemy a retreat or surrender and force them to fight to the death.

This military sense of quarter appears in Randle Cotgrave’s 1611 French-English dictionary, which defines the French quartier as

quarter, or faire war, wherein souldiers are taken prisoners and ransomed at a certaine rate.

An early use of no quarter is in a letter by James Howell to the Earl of Bristol, written after 1631 and published in 1645. Howell refers to the sack of the Protestant town of Magdeburg in 1631 during the Thirty Years War by Catholic forces of the Holy Roman Empire:

But passing neer Magdenburg, being diffident of his own strength he suffer’d Tilly to take that great town with so much effusion of bloud, because they wold receave no quarter.

Some 20,000 people died in the massacre.

Figurative use of no quarter is in place by the eighteenth century. Daniel Defoe uses it in his 1725 The Complete English Tradesman:

What shall we say to the peace and satisfaction of mind in breaking, which the tradesman will always have when he acts the honest part, and breaks betimes; compared to the guilt and chagrin of the mind, occasioned by a running on, as I said, to the last gasp, when they have little to pay? Then indeed the tradesman can expect no quarter from his creditors, and will have no quiet in himself.

No quarter can refer to either summary executions or to the lighter “not treated kindly,” which is intended depends on the context. And in the context of deploying troops, an order of no quarter should mean only one thing: a horrific crime.

Sources:

American Heritage Dictionary, fifth edition, 2020, s.v. quarter n.

Collins Dictionary, no date, s.v. no quarter.

Cotgrave, Randle. A Dictionarie of the French and English Tongues. London: Adam Islip, 1611, s.v. quartier. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Defoe, Daniel. The Complete English Tradesman. London: Charles Rivington, 1725, 96. Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO).

Howell, James. “Letter to the Earle of Bristol.” Epistolæ Ho-Eleinanæ. Familiar Letters. London: Humphrey Moseley, 1645, 5.37.41. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, accessed 1 June 2020, s.v. no quarter.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, December 2007, s.v. quarter, n.