The song Dixie is traditionally credited to Daniel Emmett, a member of and chief composer for Bryant’s Minstrels, a blackface minstrel troupe. But the famous song was not Emmett’s first use of Dixie to refer the South. He used it in an earlier song of his, Johnny Roach, which was first performed in March 1859. The song is about a slave escaping to Canada via the Underground Railroad who still longs for his homeland of the South:

Gib me de place called Dixie’s Land,

Wid hoe and shubble in my hand;

Whar fiddles ring and bangos play,

I’de dance all night and work all day.

For his part, Emmett never claimed to have coined the word. He said that he learned the term during his travels as an itinerant musician. Dixie was also the name of a character in the minstrel skit United States Mail and Dixie in Difficulties, which was first performed in 1850. The appearance of the personal name in minstrelsy may also have influenced Emmett’s use of the word.

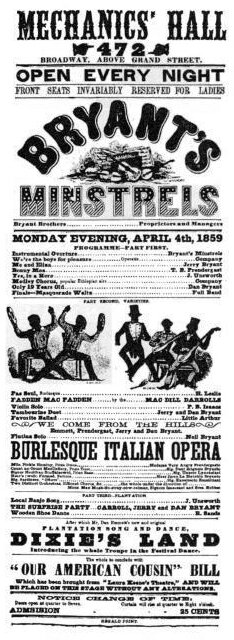

As for his more famous song, Emmett composed and first performed it about a month after Johnny Roach, on 4 April 1859. This ad from the New York Herald documents the song’s premiere:

BRYANT’S MINSTRELS

Mechanic’s Hall, 472 Broadway, above Grand

Monday April 4, and every night of the week.

BRYANT’S MINSTRELS,

the star troupe in their inimitable Soiree d’Ethiope.

BURLESQUE IRISH-ITALIAN OPERA

DIXIE’S LAND, another new Plantation Festival.

JERRY AND DAN BRYANT,

the Ethiopian Dromios, in their comicalities. Concluding with

OUR AMERICAN COUSIN “BILL.”

Doors open at 7; curtain rises at 7 ¾. Tickets 25 cents.

(Dromio is the name of one of the twins in Shakespeare’s Comedy of Errors.)

Emmett would go on to publish the song in 1860. The lyrics of the first verse and chorus of Emmett’s song, as first published, are:

I wish I was in de land ob cotton,

Old times dar am not forgotten;

Look! away! Look away! Look away!

Dixie Land.

In Dixie Land whar I was born in,

Early on one frosty mornin,

Look! away! Look away! Look away!

Dixie Land.

Chorus

Den I wish I was in Dixie, Hooray! Hooray!

In Dixie Land, I’ll took my stand, To lib and die in Dixie,

Away, Away, Away down south in Dixie,

Away, Away, Away down south in Dixie.

The song was an instant hit and was performed by many other troupes, many of whom produced versions with alternative lyrics.

While Emmett’s authorship of the song has generally been accepted, it has been disputed by some over the years. During Emmett’s lifetime, songwriter Will S. Hays claimed to have written it. (Hays also comes into the world of etymology with the history of the word gay.)

More compellingly, the Snowden family of Knox County, Ohio claim that their ancestors, freed Blacks who performed on the minstrel circuit, performed it and that it was a commonly sung by Black performers. The fact that Emmett grew up near the Snowden farm and undoubtedly knew the family, lends some credence to the claim. But while the Snowden claim is certainly possible—the history of White composers cribbing from Black musicians is a long and continuing one—I know of no firm evidence that an earlier version of the song existed. In this case, however, the absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, as we would not necessarily expect Black music from this era to be documented. So, it would seem the Snowden claim is at least plausible. At the very least, Emmett wrote and arranged the song that we know today.

But the term Dixie, or more fully Dixie’s Land or Dixey’s Land, did exist long before Emmett first performed the song or the ad appeared in the Newburyport newspaper. The writer Lincoln Ramble makes two references to a children’s game called Dixey’s Land in 1844. The first appears in New York’s The New World on 20 July 1844:

The open doors and windows exhibit old Gentlemen with very light clothing sleepily winking to the evening breeze; the boisterous children scream and throng about the pumps, or play at “Dixey’s Land” on the newly washed pavement.

The next appears in the same publication on 28 December 1844:

Doesn’t Old Fezziwig figure here like some planets in his system, crossing and recrossing their orbits, playing, “Dixey’s Land,” in the regions of space?

This last sounds like a reference to a song, but given Ramble’s use of Dixey’s Land five months earlier, it instead would indicate that he is comparing Fezziwig’s dance to the children’s game. Ramble’s use of “crossing and recrossing” also points to the game, as we can see from this description of it in the San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin of 30 July 1861:

That the philosopher and antiquarian, who seeks to discover the origin of “Dixie’s Land,” may be placed upon the track of discovery, the writer submits a few remarks upon a sport of his early childhood—often indulged in—many decades past, in the city of New York.

In reviving a recollection of the play, it is a pity that children of a larger growth cannot now settle the issues of the day upon same basis as those who in the sport of childhood held Dixie’s Land in happiness and peace. But here is the game:

On some sidewalk having a handsome stoop—such for illustration, as Lady Barken in Clinton street near Col. Rutger’s; or in Bond street, at Sam Ward’s; or Dr. Francis’s, or Philip Hone’s—a boy and girl would establish themselves as Dixie and Dixie’s wife. Imaginary lines would form the boundaries on the North and South, and the opposite party would attempt crossing the sacred domain, shouting as they entered upon it, “I am on Dixie’s Land, and Dixie isn’t home.” Soon, to their surprise, Dixie and his wife would rush to capture them, and as their position was in the centre they would soon succeed. As each one was caught he aided Dixie, and soon the whole opposing force was brought within the fold to share whatever had been united by them as the reward of entering Dixie’s Land. OLD MAN

[A game similar to the one above described has been played by the boys, from time immemorial, in Scotland. The usual cry there used, however, is: “I am on Toddy’s ground—Toddy cannot catch me.”—ED. BULLETIN.

Another reference to the game, a decidedly odd one, appears in The Opal, a journal of miscellany published by the New York State Lunatic Asylum in Utica for 1855. In a piece titled “Parlor Scene, No. 3,” two women are discussing the Mormon church over a game of chess, alluding to Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels:

Miss C.—“Joe Smith was a Brobdignag, women his Lilliputs!”

Miss J.—“Joe may be the Brobdignag of this 19th century; but our States are not Lilliputians for his rule. Yet Mr. Q——— had to be a Lilliput in Joe’s house.

Miss C.—“Those who go to Dixey’s land must be Dixey’s men.”

Miss J.—“But when Dixey comes to our land, Dixey’s not at home. Ah! Home—here woman reigns as mother, daughter, wife, and her kings submit. They keep the crown.”

(In Swift’s novel, the Brobdignags are a race of giants, while the more familiar Lilliputians are tiny people.)

Again, if one is not familiar with the children’s game, one could easily mistake this for a reference to the South and the growing political strife that would lead to war five years later.

William Wells Newell also records the game in his 1884 Games and Songs of American Children, but in this later version the children have incorporated Emmett’s 1860 lyrics:

Dixie’s Land.

This is a variety of the last game, in which a monarch instead of a fairy is the owner of the ground trespassed upon. A line having been drawn, to bound “Dixie’s Land,” the players cross the frontier with the challenge:

On Dixie’s land I’ll take my stand,

And live and die in Dixie.

The king of Dixie’s land endeavors to seize an invader, whom he must hold long enough to repeat the words,

Ten times one are ten,

You are one of my men.

All so captured must assist the king in taking the rest.

We can speculate that this New York City children’s game may have been a partial inspiration for Emmett. After all, he was living in New York at the time, and listening to the children play may have reminded him of hearing Dixie used to refer to the South and, just possibly, of an older Black song. Also of significance in the game is crossing of boundaries, which points to the Mason-Dixon line as the origin for its name.

What we have so far is that Dixey’s Land appears as a name of a boundary-crossing, children’s game in 1840s and later New York City, and perhaps this game led, in part, to Emmett’s version of the song which cemented the word’s place in the American consciousness. So it seems likely, but by no means certain, that the Mason-Dixon line is the ultimate inspiration for the terms.

But another origin story pops up in the early 1860s, shortly after Emmett’s song became a hit and a wartime anthem. The story is questionable in many regards, but it cannot be completely dismissed. Also, were this to be the actual origin for an anthem that extols the South and the slave-holding Confederacy, its origin would make the song’s use as an icon deeply ironic.

William Howard Russell, an Irish war correspondent for the Times of London, assigned to cover the U. S. Civil War, recorded this on 18 June 1861 from near Memphis, Tennessee:

On landing, the band had played “God Save the Queen” and “Dixie’s Land”; on returning, we had the “Marseillaise” and the national anthem of the Southern Confederation; and by way of parenthesis, it may be added, if you do not already know the fact, that “Dixie’s Land” is a synonym for heaven. It appears that there was once a good planter, named “Dixie,” who died at some period unknown, to the intense grief of his animated property. They found expression for their sorrow in song, and consoled themselves by clamoring in verse for their removal to the land to which Dixie had departed, and where, probably, the revered spirit would be greatly surprised to find himself in their company. Whether they were ill-treated after he died, and thus had reason to deplore his removal, or merely desired heaven in the abstract, nothing known enables me to assert. But Dixie’s Land is now generally taken to mean the seceded states, where Mr. Dixie certainly is not, at this present writing. The song and air are the composition of the organized African association, for the advancement of music at their own profit, which sings in New York, and it may be as well to add, that in all my tour in the South, I heard little melody from lips black or white, and only once heard negroes singing in the fields.

(The “organized African association” is undoubtedly a reference to Emmett and the blackface Bryant’s Minstrels.)

And there is this account, published a bit more than a week after Russell wrote the above. From the New Hampshire Sentinel of 27 June 1861:

DIXIE IS NOT A SOUTHERN SONG.—The secessionists have made “I wish I was in Dixie” their campaign song, but it does not belong to them. It is a northern production, stolen like all their other means of war. A correspondent of the New Orleans Delta tells the history of it. “I do not wish to spoil a pretty allusion, but the truth is that Dixie is an indigenous northern negro refrain, as common to the writer as the lamp-posts in New York city seventy or seventy-five years ago. It was one of the every-day allusion of boys at that time in all their out-door sports. And no one ever heard of Dixie’s land being other than Manhattan Island until recently, when it has been erroneously supposed to refer to the South from its connection with pathetic negro allegory. When slavery existed in New York, one ‘Dixy’ owned a large tract of land on Manhattan Island and a large number of slaves, and the increase of abolition sentiment caused an emigration of the slaves to more thorough and secure slave sections, and the negroes who were then sent off (many being born there) naturally looked back to their old homes, where they had lived in clover, with feelings of regret, as they could not imagine any place like Dixy’s. Hence it became synonymous with an ideal locality, combining ease, combining comfort, and material happiness of every description. In those days negro singing and minstrelsy were in their infancy, and any subject that could be wrought into a ballad was eagerly picked up. This was the case with ‘Dixie.’ It originated in New York and assumed the proportions of a song there. In its travels it has been enlarged, and has ‘gathered moss.’ It has picked up a ‘note’ here and there. A ‘chorus’ has been added to it, and from an indistinct ‘chant’ of two or three notes it has become an elaborate melody. But the fact that it is not a southern song ‘cannot be rubbed out.’ The fallacy is so popular to the contrary that I have thus been at pains to state the real origin of it.”

One needs to approach these accounts with skepticism. The one in the New Hampshire Sentinel reads like wartime propaganda designed to discredit the Confederacy and its anthem. And the idea that any slave owner, North or South, provided some sort of Elysium for his slaves is absurd, although it’s certainly possible that a northern slave owner treated his slaves relatively well compared to those in the South. And even if they hadn’t “lived in clover,” the impulse to credit the good old days is a strong one, remembering the good and forgetting the bad. So it wouldn’t be a stretch for a slave to remember his last master as better than his current one.

As to the New York connection, that state started the gradual emancipation of slaves in 1799, and slavery officially ended in 1827. But after that some born into slavery were still working off their term of service, and slaves and slave ships could visit and transit New York. So, on the surface it is plausible that a New York slave owner at the turn of the nineteenth century would want to sell off his slaves before they were emancipated and he lost those “assets.” Although, doing so would not accord with him being very kindly.

Unfortunately, for this tale, the New York Slavery Records Index does not turn up a likely candidate for the slave owner. There is a John Dixey of Manhattan who, according to the 1810 U. S. Census owned two slaves, and there are a few other Manhattan slave owners named Dixon from that period who owned one slave each. But these low numbers indicate that these were household slaves and that the men did not own large numbers of slaves or operate some kind of plantation.

Could Dixie be some slave fantasy of a better place? Could Dixie originally have referred to New York City? As much as we might want to revel in the irony, it is not likely. The evidence we have is tantalizing, but fractured and inconclusive. The Mason-Dixon line remains the most likely origin for the term.

[Update, 24 June: I deleted a reference to an alleged 1858 use of Dixie that was misdated.]

[Update, 26 June:

Barry Popik has turned up this 1841 song that is, in certain respects, the polar opposite of Emmett’s Dixie. The version I quote here is anonymous, but an 1857 version, with slightly different lyrics and set to the tune of “Betsy Baker” gives authorial credit to a Pete Morris.

“I Wish I Was in Yankee Land.” Georgetown Advocate (Washington, DC), 18 September 1841, 1. NewsBank: America’s Historical Newspapers.

I wish I was in Yankee Land,

Where once I used to be—

The land of porridge, beans and milk,

And strict sobriet—e;

The land where all the comforts that

The can yield are found—

Where piety and pumpkin pies,

And pretty girls abound.

This song, of course, tells us nothing about the origin of the word Dixie, but its reprinting in 1857 indicates that it remained popular, and it’s no stretch to think Emmett was familiar with it. Perhaps, and this is just speculation, Emmett wrote his song as a Southern response to this one.]

Discuss this post