5 August 2020

Sometimes the fiercest debates are over the smallest stakes. Such is the case with the battle between pork roll and Taylor Ham. If you’re not from New Jersey, you’re probably unfamiliar with pork roll, a pork-based, processed meat product that looks like Canadian bacon (a.k.a. back bacon or pea meal bacon), but tastes nothing like that product. The debate is over what the proper name is.

From a linguist’s point of view, both names are perfectly valid. Pork roll is a generic name for the product, while Taylor is a brand name for the product made by Taylor Provisions of Trenton, but one that is often used by the public as a generic term. Technically, the brand name is Original Taylor Pork Roll, but it is commonly referred to as Taylor Ham. There are other manufacturers of pork roll, the most famous being the Case company, also of Trenton, which has been making the product since 1870. Common wisdom, confirmed by unscientific surveys (there are no scientific ones; pork roll studies is a sadly underfunded field), is that the name Taylor Ham predominates in the northern and northwestern counties of the state, and pork roll is the more common term in central and south Jersey. (Full disclosure: having been born and bred in south Jersey, I grew up knowing it as pork roll.)

According to the Taylor company, pork roll as we know it was created in 1856 by John Taylor of Hamilton Square, near Trenton. I have found references to Taylor as a Trenton-based seller of provisions from that period, but earliest use of the term pork roll that I have found is from an advertisement in the Montreal Gazette of 7 November 1878:

Daily Supplies

Fresh Oysters!

Campbell’s Beef Hams!

Pork Rolls! Tongues!

Breakfast Bacon!

Of course, it’s impossible to say if this refers to the New Jersey delicacy or to some other meat product.

But there is an unambiguous reference to Taylor Prepared Ham being sold in Baltimore in 1896. From an ad in the Sun on 31 October 1896:

To the Trade.

We are now receiving daily shipments of TAYLOR’S PREPARED HAM. If you cannot have your orders filled by jobbers, send to us direct for prompt attention.

JNO. SCHOENKWOLF & CO., 104 S. Howard st.

A 1910 trademark dispute between Taylor Provisions and a competitor outlines the history of the product name. In the case, Taylor Provisions tried to get an injunction against the competitor for trademark violations; they lost:

The complainant is successor to one John Taylor, who conducted a provision business for a considerable time and placed upon the market a food article made of pork, packed in a cylindrical cotton sack or bag in such form that it could be quickly prepared for cooking by slicing without removal from the bag. This preparation was known as “Taylor’s Prepared Ham,” but with the passage of the pure food law by the Congress of the United States it became necessary to change the label of this article in order to avoid a violation of the statute, as it did not consist of ham. The complainant therefore adopted the name “Pork Roll,” and has had large sales of the article under the name of “Taylor’s Pork Roll,” or “Trenton Pork Roll.”

As the court noted, the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act forced the Taylor company to drop the ham from the name of the product and call it pork roll. But the public, undeterred by government edict, continues to refer to it as Taylor Ham to this day. An 18 October 1906 advertisement in the Trenton Evening Times reflects this change in the official name of Taylor’s product:

Pork Roll

Taylor’s Sugar Cured. Similar to the prepared ham sold last year under this brand. Yet much improved in every way. First of the season. Per lb. ... 17c.

And two weeks later, another ad in the same paper on 1 November 1906 touts a competing product:

Our own make pork roll (formerly called prep. ham); lb. ... 16c.

If you’re not from New Jersey, it’s impossible to fathom the ardor that is generated over whether pork roll or Taylor Ham is the proper name. Perhaps the only fiercer debate is over whether or not Central Jersey exists.

Sources:

Advertisement. The Gazette (Montreal), 7 November 1878, 2. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Advertisement. The Sun (Baltimore), 31 October 1896, 1. NewsBank: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Advertisement. Trenton Evening Times, 18 October 1906, 8, NewsBank: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Advertisement. Trenton Evening Times, 1 November 1906, 4, NewsBank: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Hyman, Vicki. “How New Jersey Saved Civilization: Taylor Ham.” NJ.com, 2 April 2019.

Stirling, Stephen. “The Results of Our Great Pork Roll vs. Taylor Ham Battle Divide N.J.” NJ.com, 16 January 2019.

“Taylor Provision Co. v. Gobel.” (Circuit Court, E. D. New York. 15 August 1910). The Federal Reporter, vol. 180. St. Paul: West Publishing Co., 1910, 939. Google Books.

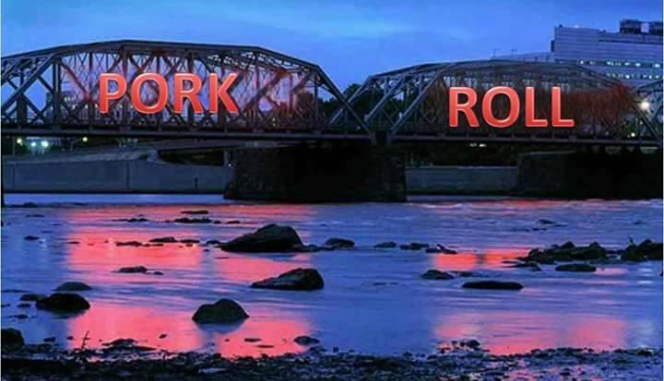

Photo credit: Pork roll, egg, & cheese sandwich, Austin Murphy, 2009, used under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license; Trenton bridge, The Pork Roll Store, Allentown, NJ.