18 August 2020

The dollar is the standard unit of monetary currency in the United States and several other countries, including Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, and Fiji. But where does the word come from?

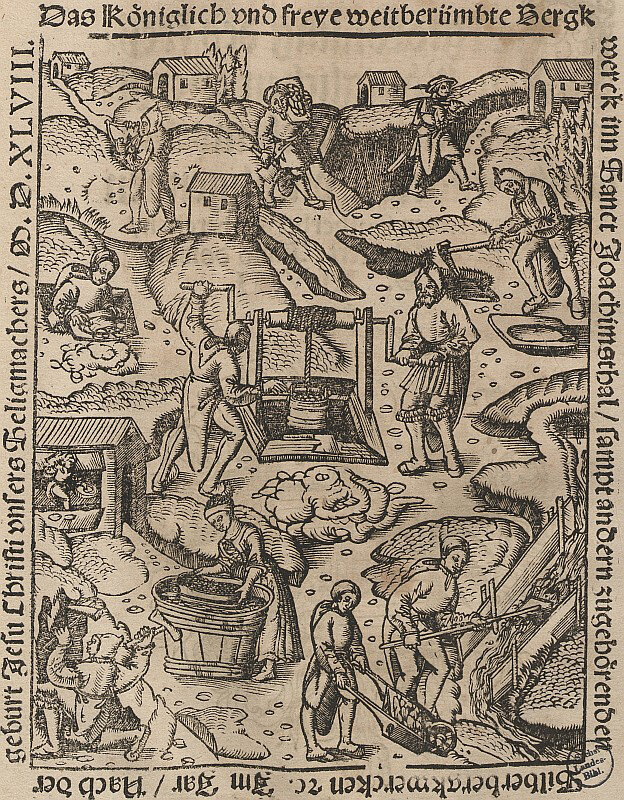

Dollar is a clipping of Joachimstaler, which in turn is from Joachimstal (literally Joachim’s valley) in Bohemia, now Jáchymov in the Czech Republic. In 1519, a silver mine there started minting coins called Joachimstalers or simply Talers. The name taler was soon applied to a variety of coins minted throughout Europe.

The word makes its English appearance in a 1553 letter by Richard Morysin and Thomas Chamberlayne, in which they refer to the European coin:

The Duke of Wirtemberg is agreed w[ith] Magister Teutonici Ordinis, so that the Duke shall have for his charges 66000 dalers; but the King of Rome will not as yet agree w[ith] Wirtemberg: The sute is now seaven years old; thes Princes wold fain end it.

But of the various coins that took the name taler or dollar, the most significant for our purposes was the Spanish peso, also known as a piece of eight, because it was worth eight reals. Here is an early English language reference to this coin as a dollar in Barnabe Rich’s 1583 Riche His Farewell to Militarie Profession. Phillip refers to Phillip II of Spain:

Many of our yong Gentlemenne vseth now adaies, in the wearyng of their apparell, whiche is rather to followe a fashion that is newe (be it neuer so foolishe) then to bee tied to a more decent custome, that is cleane out of vse: Sometime wearyng their haire freeseled so long, that makes them looke like a water Spaniell: Sometymes so shorte like a newe shorne Sheepe: Their Beardes sometimes cutte rounde like a Philippes Daler: Somtimes square like the Kinges hedde in Fishestreate: Sometymes so nere the skinne, that a man might iudge by his face, the Gentleman had had verie pilde lucke

The Spanish coin circulated widely throughout both North and South America for several centuries, and by the time of the American War of Independence was the most common coin in circulation in the English North American colonies. As a result, in 1778 Thomas Jefferson drafted legislation authorizing the new government of the United States to issue banknotes based on the Spanish peso:

Be it enacted by the General assembly that it shall be lawful for the Treasurer to issue treasury notes in dollars or parts of a dollar for any sum which may be requisite for the purposes aforesaid in addition to the sums issuable by former acts of assembly.

Six years later, in April 1784, Jefferson would suggest dollar as the name for the country’s own coinage:

The Unit, or Dollar, is a known coin, and the most familiar of all, to the minds of the people. It is already adopted from South to North? has identified our currency, and therefore happily offers itself as a Unit already introduced.

(The Oxford English Dictionary gives 1782 as the date for this note by Jefferson, and it also has a different volume and page number of Jefferson’s Works. There is clearly an error somewhere, but whether it is by the OED or by Ford, the compiler of the edition of Jefferson’s Works that I consulted, I cannot tell. In any case, there is no disputing the text or authorship of the quotation, only the exact date.)

So, the almighty dollar gets its name from a sixteenth-century silver mine in an obscure valley in what is now the Czech Republic, via the Spanish colonial empire.

Sources:

Jefferson, Thomas. “Draft of a Bill for Providing a Supply for the Public Exigencies,” 20 May 1778. In Paul Leicester Ford, ed., The Works of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 2 of 12, New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904, 327. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

———. “Notes on the Establishment of a Money Unit, and of a Coinage for the United States,” April 1784. In Paul Leicester Ford, ed., The Works of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 4 of 12, New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904, 300. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Morysin, Richard and Thomas Chamberlayne. “Letter to the Privy Council” (1553). In Edmund Lodge, Illustrations of British History, Biography, and Manners, vol. 1 of 3, London: C. Nicol, 1791, 166. Google Books.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. dollar, n.

Rich, Barnabe. Riche His Farewell to Militarie Profession. London: J. Kingston for Robart Walley, 1583. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

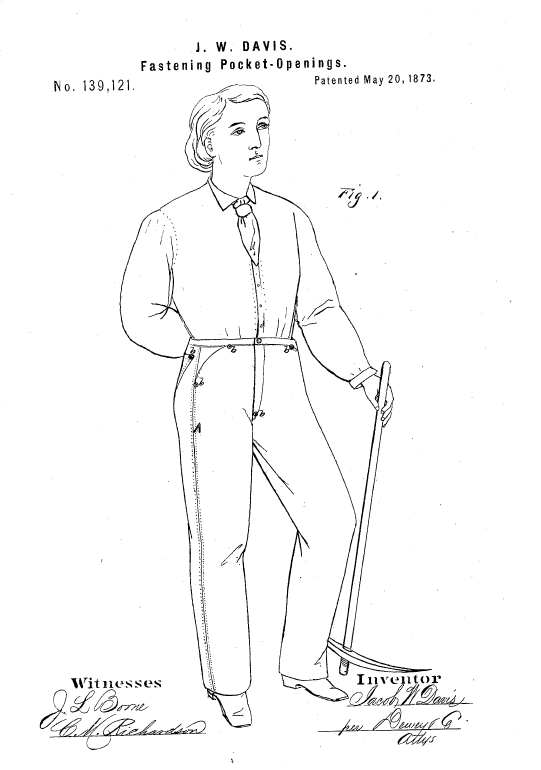

Image credits: “Bergwerk Sankt Joachimsthal,” Wikimedia Commons, public domain; U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing, 2003.