27 January 2021

Charlie has many slang meanings, but perhaps the best-known today is the American Vietnam War slang for the Vietcong, the enemy. But this sense is rooted in an older, racist term for Asians in general.

Charlie has long been a slang term for an unnamed or non-specific man, often used in informally addressing a man whose name one does not know. This sense dates to the early nineteenth century. From the New-York Mirror of 2 April 1825:

A few days ago, a gentleman being rather fatigued, called a coachee—“What will you take me about the distance of a mile for?”—“Twenty-five cents,sir.”—“Well open the door,” and in he got. In a few minutes they arrived at the place proposed.—Having alighted, the twenty-five cents was tendered—“This is not enough, sir.”—“Why, it was your price.”—“Yes, sir, but it is not enough, and I won’t take it.”—“How much is enough?”—“Half a dollar, sir”—“Well, rather than dispute with such an infernal pickpocket, I’ll pay you”—and the gentleman left Charley turning over the silver, quite satisfied with his success in making, as he expressed himself, “the flats pay for their experience.[“] Now we would seriously inquire, whether such conduct ought not to be severely punished by the proper authorities?—A law should be made to bring all such fellows to a proper sense of their duty.

About a century later, a Black English slang sense of Mr. Charlie appears in print, meaning a White person, often used contemptuously. From the glossary of Black slang terms that appears at the end of Rudolph Fisher’s 1928 Harlem Renaissance novel The Walls of Jericho:

MISS ANNE

MR. CHARLIE

Non-specific designation of “swell” whites. Ex. “Boy, bootlegging pays. That boogy’s got a straight-eight just like Mr. Charlie’s.”

This slang sense of Mr. Charlie continues up to the present day.

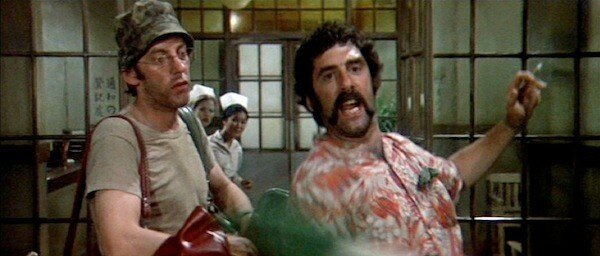

Use of Charlie to refer to an Asian, in particular a Chinese man, appears about the same time, probably influenced by the fictional Chinese-American detective Charlie Chan, who makes his literary debut in 1925 in the novel The House Without a Key by Earl Derr Biggers. The use of Charlie referring to a generic Chinese man is in place by 1938 in A.I. Bezzerides novel The Long Haul (adapted for the screen in 1940 with the title They Drive by Night, starring Humphrey Bogart and George Raft):

He walked to the Chinaman, “Hey, Charlie, what you know?”

But as with many racial slurs, the use of Charlie was not precise and could be applied to any Asian man. During World War II, the Japanese were often dubbed Charlie. From Time magazine of 9 February 1942, reporting on the fighting on the Bataan Peninsula in the Philippines:

The Jap, who is variously “Mr. Moto,” “Tojo,” “Charlie,” or “the Japanzy” to U.S. troops, was beginning to show a heavy preference for night movement, when concealment is best.

And Bedcheck Charley (also Washing-Machine Charlie) was the nickname applied to solitary, Japanese planes that harassed U.S. troops at night. From an Associated Press story of 12 January 1944 reporting from the Gilbert Islands:

First it was the snipers. Then it was trigger-happy Americans who thought they heard snipers.

But now it’s “Bedcheck Charley,” a Japanese bomber that comes over this base just as hard-working GIs settle down for a night’s sleep.

And Bedcheck Charlie would also appear on the European front late in the war, referring to solitary, harassing German planes, the term evidently having made its way there from the Pacific. From a story by a correspondent who was hospitalized on the night they received news of Franklin Roosevelt’s death in the Black newspaper the Chicago Defender:

It was the quietest night I ever experienced there for nobody talked any more and the only sounds were muffled sniffles from all of us at this blow that made us all oblivious to our wounds. When “Bedcheck Charlie,” the German plane, who strafes and bombs night convoys, came over at his usual hour, everyone was awake, but this time nobody commented on the machine-like staccato booms that every one of us knew would send in more wounded from that strafed convoy travelling up front.

In this last, the sense of solitary night raider had overridden the racist connotation of the term.

During the Korean war, the term was again applied by American servicemen referring to enemy combatants. In the cases I have found, the appellation is to Chinese soldiers, but I would think it was applied to North Koreans too. (Charlie is a difficult term to search for since there are so many uses of it as a nickname for Charles.)

Two of these refer back to the Charlie Chan origin, one obliquely and one directly. From the Austin Statesman of 17 January 1951, about soldiers on the front lines publishing a regimental newspaper:

Their paper has been put out by candlelight, Korean gaslight and flashlight. It has gone to press in bombed out buildings, abandoned factories, in the open fields, in tents and in creek beds.

Its editors sometimes have to melt the frozen ink on the stove to publish, but no difficulty yet has stopped them.

“We were busy cranking out copies six hours before Charlie Chang kicked us out of Pyongyang,” said Sgt. Fulcher, smiling. “But we made our deadline.”

And the Chicago Defender of 10 February 1951:

When Charlie Chan’s hordes struck UN forces last November, 25th Division had to high-tail it out of Chongchon River area after destroying thousands of dollars worth of equipment.

And Bed-check Charley made his appearance in Korea too. From an Associated Press piece of 20 June 1951:

“Bed-check Charley,” a single-engined Communist nuisance raider, was out again early today. The plane bombed and strafed the Uijongu area about 10 miles north of Seoul.

Having been applied to Asian enemy combatants in the last two wars, when U.S. troops entered the Vietnam War, Charlie was used there as well. From Newsweek magazine of 9 August 1965:

The American GI’s whose mission is to kill him, call the enemy simply, “Old Charley”—an elusive, slippery fellow out there somewhere, beyond the next paddy field, or lurking in the next clump of bush.

It’s commonly claimed that the Vietnam use of Charlie stems from the use of the military phonetic alphabet letters Victor Charlie to refer to the Vietcong or VC, the communist insurgents in South Vietnam. But as we have seen, this is not the origin of this use of Charlie. Rather it reinforces the existing use. And in so doing, it served two purposes that benefited the U.S. military: it served to obscure the racist origin of the term, and it helped distinguish the South Vietnamese allies from the enemy.

Sources:

Associated Press. “‘Bedcheck Charley’ Keeps GIs Awake.” Christian Science Monitor, 12 January 1944, 6. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Associated Press. “Reds Again Lose Big Jet Battle; Fight in Hills.” The Morning Call (Allentown, Pennsylvania), 20 June 1951, 1. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Boyle, Hal (Associated Press). “Regiment’s ‘Daily’ Meets Frontline Need for News.” Austin Statesman, 17 January 1951, 7. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Fisher, Rudolph. The Walls of Jericho (1928). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994, 303. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, 2021, s.v. Charlie, n., charlie, n.2, charlie, n.6, Mr. Charlie, n.

Lighter, J.E., Random House Historical Dictionary of American Slang, vol. 1. New York: Random House, 1994, s.v. Charlie or Charley, n.

New-York Mirror, and Ladies’ Literary Gazette, 2 April 1825, 287. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989 and draft additions, June 2014, s.v. Charlie | Charley, n.

“A Small Plot of U.S. Soil.” Time, 9 February 1942, 23. Time Magazine Archive.

“The War No One Wants—Or Can End.” Newsweek, 9 August 1965, 17. ProQuest Magazines.

Wilson, L. Alex. “Chatter About GIs in Korea.” Chicago Defender, 10 February 1951, 14. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Image credit: Fox Film Corporation, 1931. Public domain image.