9 February 2021

The hustings is an odd phrase that one often hears in political commentary. The hustings are the places on the campaign trail where a candidate addresses the public. To speakers of present-day English, the word has no obvious meaning except what can be gleaned from context, and it is almost always found in the plural.

Hustings is a preserved fossil from Old English. Husting, from the Old Norse hus-þing, was an assembly of household or of a noble’s retainers, as opposed to an ordinary þing, which was a more general assembly of the people. The word appears in the entry for the year 1012 in the Abingdon Chronicle II:

1012. Her on þissum geare com Eadric ealdorman & ealle þa yldestan witan, gehadode & læwede, Angelcynnes to Lundenbyrig toforan þam Eastron; þa wæs Easterdæg on þam datarum Idus Aprilis. & hi ðær þa swa lange wæron oþ þæt gafol eal gelæst wæs ofer ða Eastron; þæt wæs ehta & feowertig þusend punda. Ða on þæne Sæternesdæg wearð þa se here swyðe astyred angean þone bisceop, forþam ðe he nolde him nan feoh behaten, ac he forbead þæt man nan þing wið him syllan ne moste. Wæron hi eac swyþe druncene forðam þær wæs broht win suðan. Genamon þa ðone bisceop, læddon hine to hiora hustinge on ðone Sunnanæfen octabas Pasce—þa wæs XIII Kł. Maī—& hine þær ða bysmorlice acwylmdon, oftorfedon mid banum & mid hryþera heafdum. & sloh hine ða an hiora mid anre æxe yre on þæt heafod, þæt mid þam dynte he nyþer asah, & his halige blod on þa eorðan feol, & his haligan sawle to Godes rice asende.

(1012. Here in this year Ealdorman Eadric and all the chief counselors of England, ecclesiastical and lay, came to London before Easter—Easter Day was on the ides of April [13 April]—and they were there so long until the tribute was paid after Easter, that was 48,000 pounds. Then on the Saturday the army became roused against the bishop because he would not promise them any money, and instead he forbade that anyone pay them on his behalf. They were also very drunk because wine from the south had been brought there. The seized the bishop, took him to their husting on the Sunday evening of the octave of Easter—that was the thirteenth Kalends of May [19 April]—and shamefully put him to death there. They pelted him with bones and with the heads of oxen, and one of them struck him there with the back of an axe in the head, so that he sank down from the blow, and his holy blood fell on the earth, and his holy soul ascended to God’s kingdom.)

This sense became obsolete in the early Middle English period, except for historical references. But it continued to be used to refer to a local court of justice, especially that held in the Guildhall of London. This use is recorded c. 1100 in the Carta civibus London (Charter of the City of London), c. 1100. The text is mainly Latin, but it uses the English nomenclature for the local courts:

Et amplius non sit miskenninga in hustenge, neque in folkesmote, neque in aliis placitis infra civitatem. Et husting sedeat semel in ebdomada, videlicet die lunæ.

(And besides, there should be no mispleadings in the husting, nor in the folkesmote, nor in other pleas within the city. And the husting should sit once a week, that is on Monday.)

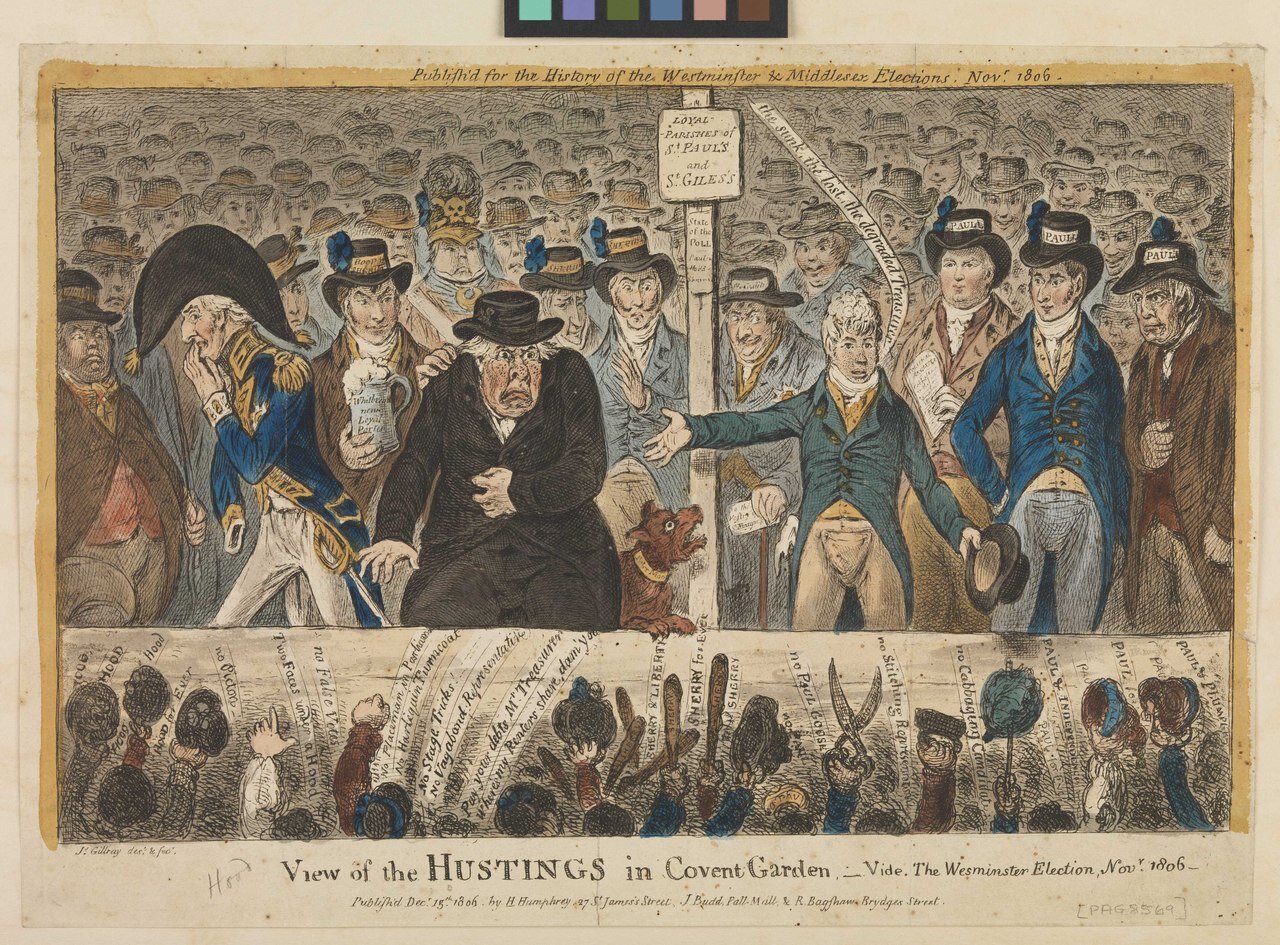

Over time, the word came to mean the raised platform on which such a court was held, particularly on those occasions when elections were held. From the London Gazette of 13–17 July 1682 regarding just such an election:

London, July 15. Yesterday the Common-Hall met, pursuant to the Adjournment made that day Sevennight, where the Lord Mayor and Aldermen being come down to the hustings, the following Order of His Majesty in Council was read.

And in Roger North’s Examen of 1740:

At Midsummer-Day, when the Common-Hall meets for the Election of Sheriffs, and the Lord-Mayor and the Court of Aldermen are come upon the Suggestum, called the Hustings, the Common Serjeant, by the Common Crier, puts to the Hall the Question for confirming the Lord-Mayor’s Sherriff, which used to pass affirmatively by the Court.

And humorist Thomas d’Urfey uses it in his 1719 collection of songs titled Wit and Mirth:

No matter pass’d in Common-Councel, of weight,

So private in th’ Morn, but I knew it at Night;

At the Pricking of Sheriffs, I could tell who would Sign,

To the chargeable Office, or else pay the Fine:

Of chusing Lord Mayors too, I found the Intrigue,

And knew which would carry’t, the Tory or Whigg;

What Tricks on the Hustings Fanaticks would play,

And how the Church Party were still kept at Bay:

With Bribery Cheats and perverting the Law,

From the First of King JAMES to the 12th of Nassau.

But by the late eighteenth century, hustings was being used to refer to electoral platforms in other cities. Edmund Burke uses it in a speech during his election to parliament for the city of Bristol:

I stood on the hustings (except when I gave my thanks to those who favored me with their votes) less like a candidate than an unconcerned spectator of a public proceeding.

And it is this sense that continues in use today.

Sources:

Burke, Edmund. “Speech to the Electors of Bristol” (3 November 1774). The Works of the Right Honorable Edmund Burke, revised edition, vol. 2 of 4. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1865, 91. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Dictionary of Old English: A to I, 2018, s.v. husting.

d’Urfey, Thomas. Wit and Mirth or Pills to Purge Melancholy, vol. 2 of 6. London: W. Pearson for J. Tonson, 1719, 242. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

The London Gazette, no. 1738, 13–17 July 1682, Gale Primary Sources: Nichols Newspapers Collection.

North, Roger. Examen. London: Fletcher Gyles, 1740, 3.8.22, 598. Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO).

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. husting, n.

Schmid, Reinhold. “Leges Henri Primi.” Die Gesetze der Angelsachsen. Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus, 1858, 435. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Whitelock, Dorothy, David C. Douglas, and Susie I Tucker. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: A Revised Translation. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1961, 91–92. London, British Library, Cotton Tiberius MS A.vi. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Image credit: James Gillray, 15 December 1806, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, England. Public domain image.