14 February 2021

[This entry makes corrections regarding Charles d’Orléans and his alleged writing of the first valentine message.]

How 14 February, St. Valentine’s feast day, became associated with love and lovers is shrouded in mystery. We do, however, have a good idea of when it happened, that is some time in the late fourteenth century, and the association was firmly in place by the fifteenth. The earliest known reference to the association is by Geoffrey Chaucer, but whether he invented it or if he was just recording it is not known.

There were several saints named Valentine, and little is known about any of them. The Valentine who is celebrated on 14 February was a martyred priest of Rome, but beyond that, his life and deeds are obscure.

The earliest reference to St. Valentine’s day being a day for lovers is in Chaucer’s Parliament of Fowls, written c.1380. The poem may have been composed to celebrate the marriage contract between King Richard II of England and Anne of Bohemia. That contract was solemnized on 2 May 1381, which is the feast day of one of the Valentines—St. Valentine of Genoa. But Chaucer could have written it for another occasion. There are multiple references to Saint Valentine’s day in the poem, so Chaucer clearly meant the poem for the feast day of one of the saintly Valentines. Lines 309–15 of that poem read:

For this was on Seynt Valentynes day,

Whan every foul cometh there to chese his make,

Of every kynde that men thynke may,

And that so huge a noyse gan they make,

That erthe, and eyr, and tre, and every lake

So ful was that unethe was there space

For me to stonde, so ful was al that place.(For this was on Saint Valentine’s day, when every fowl of every kind that man can imagine comes there to chose his mate, and then so huge a noise they did make, that earth, and air, and tree, and every lake were so full that scarcely was there space for me to stand, so ful was all that place.)

Chaucer also associates that poem with the holiday in his retraction, probably written shortly before his death in 1400, that is usually included as a coda to The Canterbury Tales. The retraction is a repentance for having written his poetry and mentions most of his works:

the book of Seint Valentynes day of the Parliament of Briddes

Chaucer again mentioned avian mating practices on Saint Valentine’s day in his Legend of Good Women, written c. 1386. Lines 143–52 read:

Upon the braunches ful of blosmes softe,

In hire delyt, they turned hem ful ofte,

And songen, “blessed be Seynt Valentyn,

For on this day I chees yow to be myne,

Withouten repentyng, my herte swete!”

And therwithalle hire bekes gonnen meete,

Yeldyng honour and humble obeysaunces

To love, and diden hire other observaunces

That longeth unto love and to nature;

Construeth that as yow list, I do no cure.(Upon the branches full of soft blossoms, in their delight, they turned to each other very often, and sang: “blessed be Saint Valentine, for on this day I choose you to be mine, without regret, my sweetheart!” And with that their beaks did meet, bestowing honor and humble services due to love, and did their other observances that conform to love and to nature; construe that as you wish, I don’t care.)

And c. 1445, poet and monk John Lydgate wrote of St. Valentine’s day too. The entry for February in a poetic Calendar of his reads in part:

Be of good comfort and ioye now, hert[e] myne,

Wel mayst þu glade and verray lusty be,

For as I hope truly, Seynt Valentyne

Wil schewe us loue, and daunsyng be with me.

O virgyn Iulyan, I chese now the

To my valentyne, both with hert and mouth,

To be true to þe, would God þat I couth.(Be of good comfort and joy now, heart of mine,

Well may you glad and very lusty be,

For as I truly hope, Saint Valentine

Will show us love, and dancing be with me.

O virgin Julian, I now choose thee

As my valentine, with both heart and mouth,

To be true to you, would God that I could.)

And a February 1477 letter from Margery Brews, to her fiancé, John Paston III opens with:

Ryght wurschypffull and welebelouyd Volentyne, in my moste vmble wyse I recommande me vn-to yowe.

So, it is clear that by the latter half of the fifteenth century the traditions of St. Valentine’s day, including sending love poetry to one’s lover was well established.

It is often claimed that the first valentine poem or message written to a lover is one by Charles, Duke of Orléans, allegedly penned while he was imprisoned in the Tower of London following his capture at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415. Charles remained a prisoner of the English until 1440. (As a member of the French royal family he was treated rather well, and only a portion of this captivity was spent in the Tower. Most of it was as a “guest” at various noble estates..)

The poem in question, which is indeed by Charles, reads:

Je suis desja d'amour tanné,

Ma tres doulce Valentinée,

Car pour moi fustes trop tart née,

Et moy pour vous fus trop tost né.

Dieu lui pardoint qui estrené

M'a de vous, pour toute l'année.

Je suis desja d'amour tanné,

Ma tres doulce Valentinée.Bien m'estoye suspeconné,

Qu'auroye telle destinée,

Ains que passast ceste journée,

Combien qu'Amours l'eust ordonné.

Je suis desja d'amour tanné,

Ma tres doulce Valentinée.(I am already sick of love,

My very gentle Valentine,

Since for me you were born too late,

And I for you was born too soon.

God forgives him who has estranged

Me from you for the whole year.

I am already sick of love,

My very gentle Valentine.Well might I have suspected

That such a destiny,

Thus would have happened this day,

How much that Love would have commanded.

I am already sick of love,

My very gentle Valentine.)

The problem is that the poem was not written in England, but rather after he had returned to France, sometime during 1443–60. And many other poets, such as the aforementioned Chaucer and Lydgate, as well as Christine de Pizan had written Valentine’s Day poetry before this. Not to mention that Charles himself wrote some fourteen other poems, in both French and English, with Valentine’s Day as the theme.

But this poem is not a message to a lover, but rather part of a Valentine’s Day practice of holding a lottery which would pair male and female members of the court. The man would serve as the woman’s valentine for the coming year, a ritual enactment of courtly love. In the poem, Charles is telling the much-younger woman he is paired with that he is too old and tired for such nonsense. Rather than writing the first valentine poem, Charles may have written the first anti-Valentine.

Sources:

Charles, d’ Orléans. Poesies. Paris: C. Gosselin, 1842, 245–46. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Chaucer, Geoffrey. The Riverside Chaucer. Larry D. Benson, ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1987.

Davis, Norman, ed. Paston Letters and Papers of the Fifteenth Century, vol. 1 of 3. Early English Text Society, S.S. 20. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2006, Item #416, 663. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Jackson, Eleanor. “Charles d'Orléans, earliest known Valentine?” Medieval Manuscripts Blog, British Library, 14 February 2021.

Lydgate, John. “A Kalendare.” The Minor Poems of John Lydgate. Henry N. MacCracken, ed. Early English Text Society, extra series 107. London: Kegan, Paul, Trench, Trübner, and Co., 1911. 364. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Middle English Dictionary, 2019, s.v. valentin(e, n.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. Valentine, n.

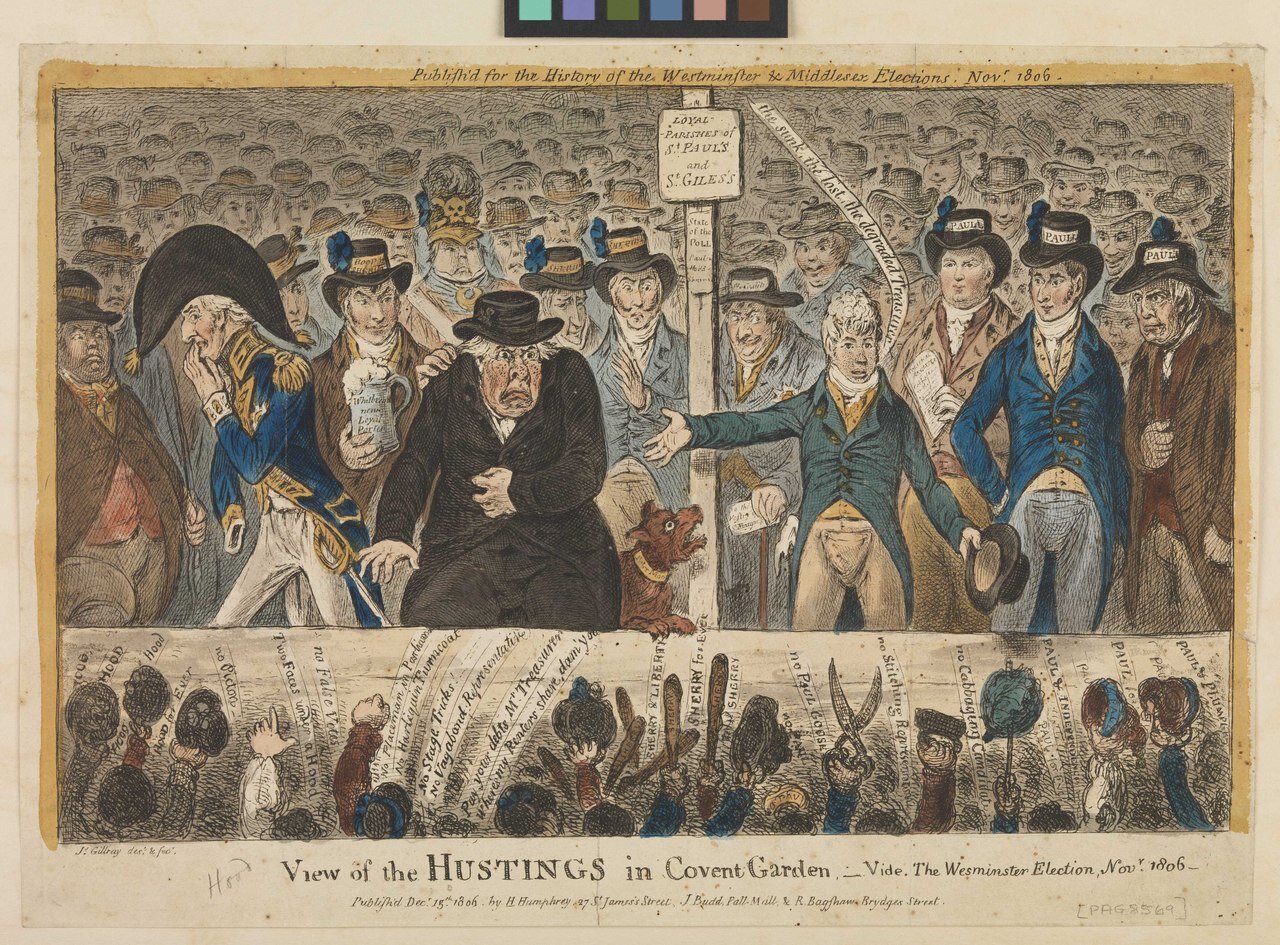

Image credit: Oxford Bodleian Library MS Bodl. 264, fol. 59r. In public domain as a mechanical reproduction of a work created before 1925.