8 March 2021

Metes and bounds is a legal term used in real property law. Black’s Law Dictionary defines it thusly:

1. The territorial limits of real property as measured by distances and angles from designated landmarks and in relation to adjoining properties. 2. The method of describing a tract by limits so measured, esp. when the descriptions of the limits are arranged as a series of instructions that, if followed, result in traveling along the tract's boundaries.

Bounds remains familiar to present-day speakers, but metes has passed into the realm of arcane legal jargon. Both terms were borrowed from Anglo-Norman French.

Bound appears in English by the late thirteenth century, at first as a noun denoting a stone property marker, later generalizing to the property line itself. It appears in the poem Laȝamon’s Brut, a poetic, fanciful history of Britain. The poem survives in two extant manuscripts, both dating to 1275–1300, but it was probably composed c. 1200. This particular instance is of note not only because it is an early appearance of a form of the word bound, but it also marks the shift from an Old English predecessor to the Anglo-Norman term in English writing. The relevant passage in the manuscript British Library, MS Cotton Caligula A 1x (from here on out “Caligula”) reads:

Þa comen heo to þan bunnen.

pa Hercules makede; mid muchelen his strengðe.

pat weoren postes longe; of marmon stane stronge.

Þat taken makede Hærcules; pat lond þe þer-abuten wes.

swiðe brod & swiðe long; al hit stod an his hand.(Then they came to the bounds

That Hercules had made, with his great strength.

It was made of long posts of strong marble.

Hercules had made that token: that the land thereabout was

very broad and very long; it all stood in his possession.)

But the other manuscript, Cotton Otho C Xiii (that is Otho), uses the word wonigge instead of bunnen. The word wunung is Old English meaning dwelling or place of habitation, and its Early Middle English use could denote land or country. The line in the Otho manuscript reads:

Þo comen hi to þan wonigge þat Hercules makede.

(Then they came to the land that Hercules founded.)

In this instance the Otho manuscript is using an older English word, while the Caligula manuscript is using a synonym recently borrowed from Anglo-Norman. One might think from this example that Otho was copied earlier, but that is not necessarily the case. In other places Otho uses a recent Anglo-Norman borrowing where the Caligula manuscript uses a word from Old English. One such case is the following passage: Caligula uses the older marmon stane where Otho uses the Anglo-Norman form with the later plural inflection marbre stones. The original version, which is lost, undoubtedly used the older Old English forms in both these cases. The two manuscripts are an example of the language changing “in real time,” and it’s a haphazard and uneven process where the scribes are not being consistent in which forms they choose.

(The names Otho and Caligula seem odd to the uninitiated. Robert Cotton, whose library formed the core of the British Library’s manuscript collection, housed his manuscripts in presses topped with busts of Roman emperors, and the manuscript shelf marks retain this designation to this day.)

The form boundary doesn’t make its appearance until the Early Modern era. Here’s an example from the appropriately named John Manwood’s 1592 A Brefe Collection of the Lawes of the Forest:

Some do make this definition of a forest, vz, a forest is a teritory of grounde, meered and bounded with vnremoueable markes, méeres and boundaries, ether knowen by matter of recorde, or else by prescription. This is no perfect definition of a Forest, neitheir, because it doth not concist Ex genere & vera differentia: for by this definition Westminster Hall may be a Forest.

Also borrowed from Anglo-Norman, mete makes its English appearance about a century later in the 1401 poem “The Reply of Friar Daw Topias,” only here it represents a metaphorical, rather than a physical, boundary:

Thou jawdewyne, thow jangeler,

how stande this togider,

by verré contradiccion

Thou concludist thi silf,

and bryngest thee to the mete

there I wolde have thee.(You jester, you idle talker,

how does this make sense?

by true contradiction

You disprove yourself

and bring you to the mete

there I would have you.)

Here mete is being used in its original sense of a point or position, a target or mark. Like the original meaning of bound, it could be used to refer to a boundary marker.

The phrasing metes and bounds is in place by 1473 when printer William Caxton uses it in his translation of Raoul Léfevre’s history of Troy:

After they had seen the batayll of kynge antheon difrenged and broken they myght not lifte vp their armes to dyffend them but were slayn a lityll and a lityll. And fynably they were brought to so strayte metes and boundes that they wiste neuer where to saue hem. And than they fledd out of the place sparklid by the feldes & champayns.

(After they had seen the battalions of King Antheon destroyed and broken they would not lift up their arms to defend themselves but were slain little by little. And finally, they were brought to such constricted metes and bounds that did not now where to go to save themselves. And then they fled out of that place, scattered about the fields and plains.)

What we have here is a very old term that survives, in fossilized form, in legal jargon. This is not at all unusual; jargon of various professions often contains words or senses of words that are otherwise obsolete.

Sources:

Anglo-Norman Dictionary, AND2 phase 3, 2008–12, s.v. mete1; AND2 phase 2, 2000–06, bounde1.

Brook, G. L. and Roy Francis Leslie, eds. Laȝamon: Brut. Early English Text Society 250. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1963, lines 658–62, 34–35. London, British Library, MS Cotton Caligula A 1x and Cotton Otho C Xiii. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Garner, Bryan, ed. Black’s Law Dictionary, 11th edition, 2019, s.v. metes and bounds. Thomson Reuters: Westlaw.

Léfevre, Raoul. Here Begynneth the Volume Intituled and Named the Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye. William Caxton, trans. Bruges: William Caxton, 1473, leaf 181r-v. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Manwood, John. A Brefe Collection of the Lawes of the Forest. London: 1592, 138. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Middle English Dictionary, 2019, s.v. mete, n.(2), bound(e, n., woning(e ger.(1), marble, n.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, December 2001, s.v. mete, n.1; second edition, 1989, s.v. bound, n.1, boundary, n.

Wright, Thomas. “The Reply of Friar Daw Topias, With Jack Upland’s Rejoinder” (1401). Political Poems and Songs Relating to English History, vol. 2 of 2. London: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts, 1861, 86–87. Oxford, Bodleian MS Digby 41, fol. 2r. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

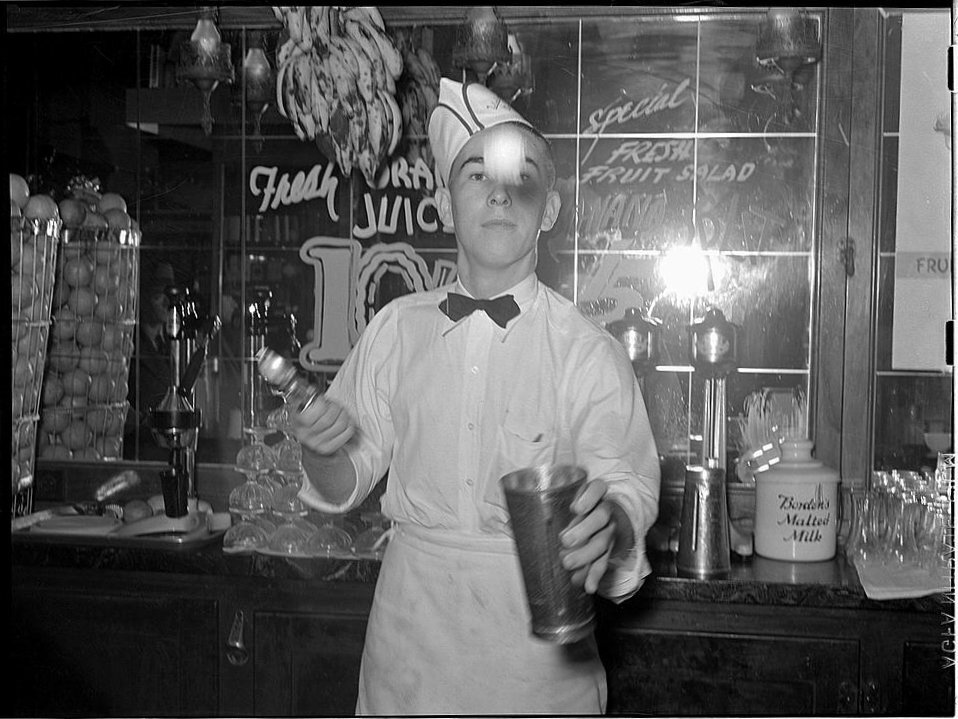

Photo credit: Unknown photographer, 1913. Public domain image.