9 April 2021

To live the life of Riley (or Reilly) is to have a carefree and luxurious existence. But the Riley to which the phrase refers is a bit of mystery. We don’t know who he was or if it even refers to a specific person. There is one candidate who stands out from the rest, but his connection to the phrase is tenuous.

What we know for sure is that the phrase was well established by December 1911, the first time it appears in print, or that’s at least the earliest anyone has found as of this writing. It appears in the pages of the Hartford Courant on 6 December 1911 in a story about a stray cow who had been living it up on the produce in farmers’ fields for a year before it met an untimely demise:

The famous wild cow of Cromwell is no more. After “living the life of Riley” for over a year, successfully evading the pitchforks and the bullets of the farmers, whose fields were ravaged in all four seasons, the cow today fell a victim to a masterfully arranged trap, and tonight lies skinned and torn into quarters at the home of Jesse Canfield in Rocky Hill.

Poor cow, but it’s better to die free than live as slaves, I guess.

There are a number of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century candidates for the position of Riley, both real and fictional. The name appears in any number of music-hall ballads, but only one has any evidence linking him to the phrase. A few years before the Cromwell cow went renegade, the phrase living the life of Willie Reilly appears in a letter sent to the Bridgemen’s Magazine, a journal of a labor union of bridge and iron workers, which was published in August 1909:

Paddy O’Malley is living the life of Willie Reilly. He has his Colleen Bawn out on a farm, half of which is planted with potatoes, the other half acre with cabbage, and in the left corner is a little sty, with two runts in it. This little crop, Paddy says, will last until next summer, and if he has any left he will give it to the steel car manufacturers, as the poor fellows have a hard struggle trying to lick the dagoes.

Of course, you can’t have an early twentieth century phrase without some racism.

But who was Willie Reilly? He is a pseudo-historical figure who supposedly lived in Ireland c. 1790. There are various versions of his story, but he is generally supposed to have been a minor, Catholic landowner who eloped with a Helen Ffolliott, the daughter of a local, Anglo-Irish squire. He was tried for abducting Helen but acquitted after she professed her love for him. In some versions the woman is named Caillin ban or Colleen Bawn, which simply means young girl, white.

Whether or not any of this actually transpired doesn’t matter as far as the phrase is concerned because the story was immortalized in a number of ballads, the earliest being titled Riley and Colinband and published c. 1795. But that ballad, as well as most of the others, does not use the phrase life of Riley.

One version of the story, however, does use the phrase, or at least that co-location of words, for in the song the phrase doesn’t denote a life of leisure. In this passage, Riley is on trial, facing execution if convicted, and the speakers are his defense counsel, Fox, and Squire Ffolliott, Helen’s father. The ballad is published as the preface to William Carleton’s 1855 telling of Reilly’s story:

Then out bespoke the noble Fox, at the table he stood by,

“Oh, gentlemen, consider on this extremity,

To hang a man for love is murder you may see,

So spare the life of Reilly, let him leave this countrie.”“Good my lord, he stole from her her diamonds and her rings,

Gold watch and silver buckles, and many precious things,

Which cost me in bright guineas more than five hundred pounds,

I’ll have the life of Reilly should I lose ten thousand pounds.”

Here the life of Reilly refers to his execution, and the ballad says nothing about his living happily ever after, although one may presume he did by the ballad’s silence on the matter.

The story was still familiar to Americans in the opening years of the twentieth century. The following exchange of letters appears in the Jersey Journal in December 1912, just over a year after the Cromwell cow incident. The letters show that both the phrase and the story of William Reilly were well known at the time. First from a letter printed in the journal on 13 December:

“LIFE OF REILLY”

Editor Jersey Journal:

Sir:—Am in this country nearly fifteen years and many things puzzle me. I hear very often about the “Life of Reilly.” Who was Reilly, and kind of life did he lead? Please tell me if they have the “Life of Reilly” at the Free Public Library, and oblige,

Your constant reader,

Arthur Gilson.

The editor responded:

Many men named Reilly have become famous, and the query is one sure to provoke discussion from the intelligent readers of this column. We recall now three heroes named Reilly, and perhaps one of them is responsible for the rattling in Mr. Gilson’s knowledge box. There was Willie Reilly who, when his troubles were ended, lived happy ever with the Colleen Bawn. Then there was the famous gentleman asked about in the song, “Is That Mr. Reilly That Keeps the Hotel.” The third Reilly was also celebrated in song by his chum, who no matter what he had, “Handed It Over to Reilly.” We do not think they have the “Life of Reilly” at the Public Library, but if there is such a life J. Pierpont Morgan must have it.

—Ed.

And the next week, on 17 December 1912, the following letter appeared:

Dear Sir—Your very clever answer to Mr. Gilson’s inquiry about the “Life of Riley” nearly caused a riot in our hitherto peaceful home. To your three famous Reillys, allow me to add an entry. I refer to the famous Reilly we used to sing about in the ditty, “I Won’t Go Out With Reilly Any More.” If Mr. J. P. Morgan has not the life of Reilly, Andrew Carnegie surely has—and he can be induced to part with it.

Tom Gannon.

The reference to J. Pierpont Morgan is undoubtedly to the Morgan Library in New York City, and Andrew Carnegie’s philanthropy funded public libraries around the world.

So, Willie Reilly is the leading contender for being the inspiration for the life of Riley, at least people at the turn of the twentieth century thought he was. But the evidence is too thin for us to declare it so with confidence.

Sources:

“Bullet Ends Life of Famous Wild Cow” (5 December 1911). Hartford Courant (Connecticut), 6 December 1911, 1. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Carleton, William. Willy Reilly and His Dear Coleen Bawn. New York: George Munro’s Sons, 1855, 5. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Kelley, J. L. Letter. The Bridgemen’s Magazine, 9.8, August 1909, 486. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, December 2020, s. v. Riley, n.

“Queries and Letters Sent to the Editor.” Jersey Journal (Jersey City, New Jersey), 13 December 1912, 20; 17 December 1912, 14. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Riley and Colinband. c. 1795. Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO).

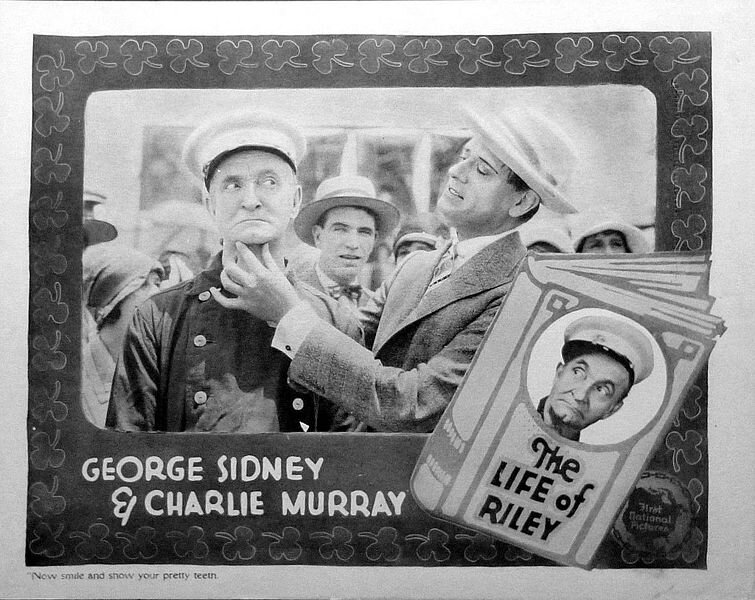

Image credit: First National Pictures, 1927, public domain image.