14 June 2021

Catawampus is a protean, nonsense word. It has no specific meaning, changing to fit the circumstances. Over the years it has meant askew, total or totally, excessive or excessively, ill-tempered, a fanciful creature, and so on. Similarly, it has been used as an adjective, noun, verb, adverb, exclamation, and proper name. Its one unwavering feature is that is used in jocular or non-serious contexts. It appears in the United States by 1830 and rather quickly spreads to the rest of the English-speaking world.

The earliest use that I have found is as an adverb meaning askew or obliquely. In this sense it may have been influenced by catercorner. It appears in the 12 June 1830 Carolina Sentinel in a mention of a slang/dialect dictionary:

New Dictionary.—The Augusta Courier gives a specimen of the Cracker Dictionary, an unpublished work; the following are some of the definitions:

Bodiaciously—means corporeously.—Catawampusly, obliquely, bias.

(I’ve been unable to locate the relevant issue of the Augusta Courier or a copy of the Cracker Dictionary—if it was ever published.)

Its use as an adjective meaning askew or warped can be seen in this humor piece in the September 1852 issue of the North Carolina University Magazine:

Consequently the circle or circular figure is the most beautiful shape in nature. Young gentlemen seem to be aware of this, and by means of a material called hair they contrive to manufacture faces of all forms, from a perfect circle to a catawampus ellipse. If they want an elliptical face, they create a patch of hairs on the chin. This lengthens the transverse axis, and, as all mathematicians know, causes the face to depart from the circular form and assume the elliptical one required. If they want a circular face, they lay two equal batches of hair on, beneath each ear, this increases the conjugate axis, and causes the ellipses to approximate to the circle—thus are circular and elliptical faces constructed.

Another very early use is as an adverb meaning totally, completely. From the 11 June 1834 Gloucester Telegraph (Massachusetts):

Fates of Deserters.—Charles Green, boatswain’s mate, a deserter from the U. S. ship St. Louis, and James Medlar, a deserter from the U. S. ship Delaware, received their rations in the gangway of the U. S. Flag ship Hudson, on Friday last, at the navy yard in Brooklyn: when they were politely handed into a boat, and drummed ashore stern foremost! This is what we should term, “tee-to-tolly ramquaddled, and catawampously chawed up.” The poor fellows looked like motherless colts.—N. Y. Sun.

Catawampusly chawed up was an idiom, appearing in many other sources, such as the Weekly Ohio State Journal of 26 April 1843:

From the New York Aurora of Thursday.

“The Election.—Final Result.—The ascertained result of the election, on Tuesday, is even more glorious than we stated yesterday. Never was a poor set of devils so tetotaciously and catawampously chawed up and exflunctificated as the Whigs. Their writhings yesterday were dreadful to behold,” and so on.

And in another dozen years, catawampously chawed up had reached India, as seen in the Bombay Times and Journal of Commerce of 8 October 1845:

Our readers will not have forgotten that we lately drew attention to the undignified behaviour of the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court at Bombay, in the matter of a misunderstanding which existed between the Advocate General and himself, on the subject of some real or supposed official error committed by the former party, with reference to certain criminal cases set down for trial before the Court. They will remember also that his Lordship at the same time threatened to invoke the displeasure of the local Government against their delinquent Law Advisor, and that the learned gentleman might in short consider himself a highly favored individual, if he was not “catawampously chawed up” and made a caution to all future advocates in something less than no time.

It could also be an adjective meaning excessive. From an article about the California Gold Rush in the Newark Daily Advertiser of 2 February 1849 (and reprinted in many papers on both sides of the Atlantic):

Toted my tools to Hiram K. Doughboy’s boarding shanty and settled with him for blankets and board, at 30 dollars per diem. Catawampus prices here, that’s a fact; but every body’s got more dust than he knows what to do with.

Nineteenth-century newspaper editors loved to engage in wordplay, and catawampus was even used as an epithet for the Roman god Jupiter in the Charleston Mercury of 29 July 1844:

The thunderbolt has burst—Jupiter Catawampus has taken the matter in hand—Malvolio is honest, and there shall be no more cakes and ale!!! Let the earth tremble—let the State Rights party hang its head and body too—let Free Trade go a wool-gathering—let South Carolina, as Henry the Eighth said to the Lady Abbess, “go spin, hussy!” It is really all over with us, and what adds to the calamity is the appalling suddenness of its catastrophe. The editor of the Courier has come out for the Union and the Tariff, and is favorable to consolidation generally? and he doesn’t care who knows it.

It could be an adjective meaning ill-tempered, as seen here in Robert Carlton’s 1843 tale of the American frontier, The New Purchase:

The tother one what got most sker’d, is a sort of catawampus (spiteful) and maybe underhand wouldn’t stick to do you a mischief if he thought you made a laff on him—albeit, he’s been laffed at a powerful heap afore.

Catawampus could also be a disease, something of a dreadful lurgy. In this case, it refers to seasickness, from the New Orleans Weekly Delta of 21 September 1846:

Night came on, and I—“Young Maryland,” as I was styled—just as I was engaged in the humane task of pouring a brandy toddy down the throat of “Old Kentuck,” was taken with an awful fit of the catawampus. Oh, Delta—beloved Delta, were you ever sea-sick? Think of it, and weep—yea, shed about fourteen gallons of tears. The vessel, like some Titan’s cradle, rocking at the rate of two miles per minute—the sea in an “orful skuirl”—twenty-seven unhappy wretches extended on the wet cabin floor, and each of them attended by a large——wash basin!

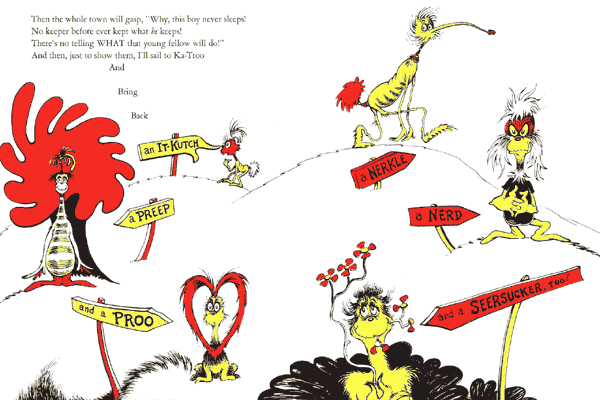

And catawampus could mean some mysterious or fearsome creature. This sense may have been influenced by catamount, another name for the North American mountain lion. From Bill Arp’s fictitious 1866 memoir of his time in the Confederate congress:

My opinion is, that some other Bill might have been found that would have done better or worse. One might have been discovered on the coast of Africa, or in the Lake of Good Hope, or somewhere in the Mediterranean Mountains, but Congress was, I suppose, afraid to run the blockade after it. If they had applied to your distinguished and humble fellow-citizen, I would have undertaken the job. But, alas! they didn't. On the contrary, they barred the doors, and shut the window blinds, and let down the curtains, and stopped up the keyholes, and went into a place called SECRET SESSION, which is perhaps a little the closest communion ever established in a well-watered country. A grand jury or a Masonic Lodge, or a Know-Nothing convention, isn't a circumstance to it. It is a thing that plots, and plans, and schemes for a few weeks, and then suddenly pokes its head out like a catawampus and says, Booh! Then all the pop-eyed folks run about and say, Booh! Booh!! And the peaceable, anti-bullet citizens begin to tremble in the knees, and say, Booh! Booh!! Booh!!! And it keeps travelling faster and faster, and growing bigger and bigger, until it reaches the Governor, and he is constrained to get on a fodder-stack pole and say in a loud voice, Booh! Booh!! Booh!!! Booh!!!! B-o-o-o-o-o-o-h!!!!!

With no fixed origin or literal meaning, catawampus can, and has been used, to mean a wide variety of things. It means whatever the context demands it mean.

Sources:

Arp, Bill (pseudonym of Charles Henry Smith). Bill Arp, So Called. A Side Show of the Southern Side of the War. New York: Metropolitan Record Office, 1866. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

“The Bombay Supreme Court Quarrel.” Bombay Times and Journal of Commerce, 8 October 1845, 662. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Times of India.

Carlton, Robert (pseudonym of Baynard Rush Hall). The New Purchase: Or, Seven and a Half Years in the Far West, vol. 1 of 2. New York: D. Appleton, 1843, 265. .

“Charleston.” Charleston Mercury (South Carolina), 29 July 1844, 2. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Dictionary of American Regional English, 2013, s.v. catawampus, n., catawampus, adj., catawampus, adv., catawampus, v.

“Fates of Deserters.” Gloucester Telegraph (Massachusetts), 11 June 1834, 1. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

“A Few Days in the Diggings.” Newark Daily Advertiser (New Jersey), 2 February 1849, 2. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, 2021, s.v., catawampus, n., catawampus, adj., catawampus, v., catawampus!, excl., and catawampusly, adv.

“Odds and Ends.” Carolina Sentinel (Newbern, South Carolina), 12 June 1830, 1. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. catawampous, adj.

“The Policy of the Administration and Its Men.” Weekly Ohio State Journal (Columbus), 26 April 1843, 3. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

“Sketches of Travel.—No. 1.” New Orleans Weekly Delta, 21 September 1846, 8. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

“Something About Beauty and Ugliness.” North Carolina University Magazine, 1.7, September 1852, 283–84. HathiTrust Digital Archive.