14 July 2021

Like many other North American place names derived from Indigenous names, the exact origin of Manitoba and its original meaning are uncertain. The early European explorers, fur trappers, and settler-colonists were generally not very good at recording Indigenous languages. But the name most likely comes from an Algonquian language, either the Ojibwa Manito-Bah or Cree Manito-Wapow, both meaning “strait of the spirit,” a reference to the sound of the water on the shores along the narrows of what is now called Lake Manitoba. A less likely possibility is that it is from the Assiniboine (Western Siouan) Mini-Tobow, meaning “lake of the prairie.”

The name was first applied to Lake Manitoba, and only later to the surrounding territory. The earliest English-language reference to the name I have found is from Alexander MacKenzie’s 1801 A General History of Fur Trade from Canada to the North-West:

The next river of magnitude is the river Dauphin, which empties itself at the head of St. Martin's Bay, on the West side of the Lake Winipic, latitude nearly 52. 15. North, taking its source in the same mountains as the last-mentioned river, as well as the Swan and Red-Deer River, the latter passing through the lake of the same name, as well as the former, and both continuing their course through the Manitoba Lake, which, from thence, runs parallel with Lake Winipic, to within nine miles of the Red River, and by what is called the river Dauphin, disembogues its waters, as already described, into that Lake.

From the English perspective, the territory that makes up present-day Manitoba was administered by the Hudson’s Bay Company starting in the seventeenth-century. The French started trading in the area in the 1730s, and in 1779 the Montreal-based North-West Company was formed, which competed with Hudson’s Bay, sometimes violently. The two companies would merge in 1821, but the following account of events from 1816, published in 1819, describes the origin of one such violent incident between the competing companies. The account is written by Frederick Damien Heurter, an employee of the North-West Company. The use of half-breed is a derogatory reference to the Métis people of the region. (The Métis are one of the three major Indigenous groups in Canada, originating from the intermarriage of European and Indigenous people, but maintaining a distinct culture. The other two groups are the First Nations and the Inuit.) Heurter wrote:

Alexander McDonell, partner of the North-West Company, arrived at Fort Douglas the 3rd of September, when he was received with discharges of artillery, and treated the half-breeds with a ball and plenty to drink, the same evening. Next day news arrived, that Peter Fidler, a trader in the service of the Hudson's Bay Company had arrived, with an assortment of goods at Lake Manitoba, having sent word to the freemen to go and receive some payments due to them; when this was reported to Alexander McDonell, he said “Que Diable qu'est-ce qu'il a à faire là, il faut aller le piller" [What the Devil is he doing here? We have to go and loot him]. The sarne day he told me to hold myself in readiness to go next morning with a party of half-breeds to pillage the said Petet Fidler, to which I made no answer.

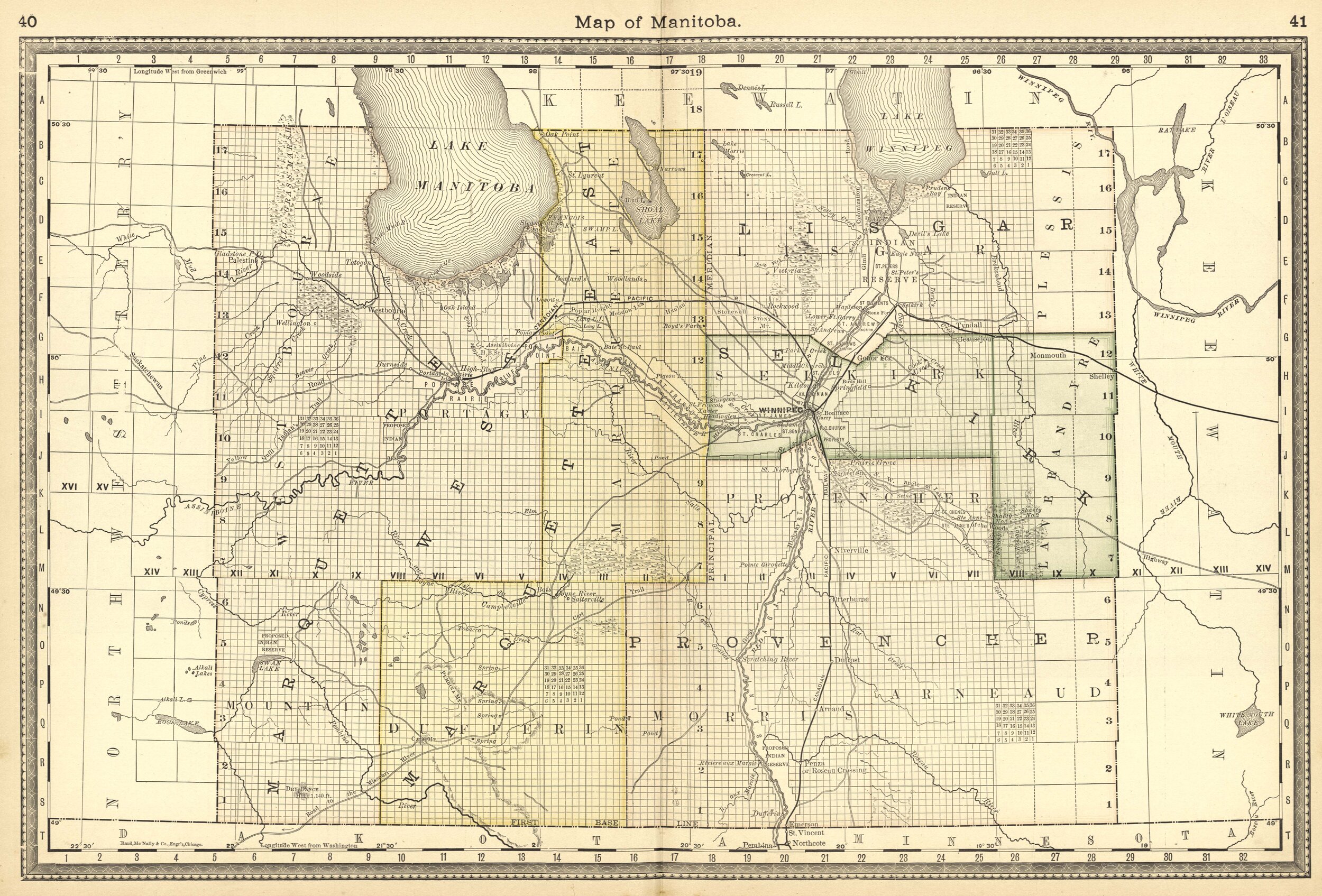

The Hudson’s Bay Company ceded its land to Canada in 1869, and the province of Manitoba was formed in 1870. But this original “postage-stamp” province was only one-eighteenth of the province’s current size. The province gradually grew, taking land from the Northwest Territories, until 1912, when it reached its current size.

Sources:

Everett-Heath, John. Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Place Names, sixth ed. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2020, s.v. Manitoba. Oxfordreference.com.

Heurter, Frederick Damien. “Narrative of Frederick Damien Heurter, late Acting Serjeant-Major, and Clerk in the Regiment of De Meuron.” Narratives of John Pritchard, Pierre Chrysologue Pambrun, and Frederick Damien Heurter, Respecting the Aggressions of the North-West Company, Against the Earl of Selkirk’s Settlement Upon Red River. London: John Murray, 1819, 76. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

MacKenzie, Alexander. A General History of Fur Trade from Canada to the North-West. 1801, 80. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Rayburn, Alan. Oxford Dictionary of Canadian Place Names. Don Mills, Ontario: Oxford UP Canada, 1999.

Image Credit: Historical Hand-Atlas. Chicago: H.H. Hardesty, 1882, 40–41. Library of Congress.