27 September 2021

Ring Around the Rosie (or Ring a Ring o’ Roses, or other variant spellings) is a children’s song and game where the children join hands, dance in a circle, sing, and at the end they all fall to the ground. Or at least that’s how the game is commonly played nowadays. The origin of the rhyme is rather straightforward; the phrase comes from May Day or Whitsunday (Pentecost) traditions of dancing and gathering garlands or wreathes of flowers, traditions that date to the medieval era. Versions of the song, and they are myriad, are found in a number of European languages, and at the end the children usually either fall down, curtsy, or choose a sweetheart.

While the flower-gathering tradition dates to the medieval era, the song itself is not nearly that old. The earliest recorded versions date to the late eighteenth century but are likely older in oral use. (Efforts to record folklore and culture of children did not begin in earnest until the nineteenth century.) In his 1883 Games and Songs of American Children, William Wells Newell claims this version was in use in New Bedford, Massachusetts in 1790:

Ring a ring a rosie,

A bottle full of posie,

All the girls in our town,

Ring for little Josie.

Unfortunately, Newell does not give any evidence to support his claim of a 1790 date, but the date is a plausible one, and there is no particular reason to doubt it. For we do have a version from Germany that is recorded in a 1796 collection of folklore:

Ringe, Ringe, Reihe!

Sind der Kinder Dreie,

Sitzen auf dem Holderbusch,

Rufen alle: musch, musch, musch!

Setzt euch nieder!(Ring-a, ring-a, row!

There are three children

Sitting in the holderbush,

All call out: musch, musch, musch!

Sit down!)

The earliest appearance in English with solid evidence is from 1855 in Ann S. Stephens’s novel The Old Homestead. The rhyme appears as the epigraph for a chapter titled, “The Festival of Roses”:

A ring—a ring of roses,

Laps full of posies;

Awake—awake!

Now come and make

A ring—a ring of roses.

And the text of that chapter explains the reason why Stephens chose the rhyme to introduce the chapter:

Among the first and the busiest were Mary Fuller and Isabel. They sat beneath a great elm tree back of the Hospital, with a heap of flowers between them, out of which they twined a world of bouquets, fairy garlands, and pretty crowns. Half-a-dozen little girls, lame, or among the convalescent sick, volunteered to gather the flowers, and some of the larger boys were up among the branches of the elm tree, garlanding them with ropes of the coarser blossoms.

[...]

Then the little girls began to seek their own amusements. They played “hide and seek,” “ring, ring a rosy," and a thousand wild and pretty games; for the place was so beautiful, and the day so bright, the little rogues quite forgot that they were in the Poor House, or had ever been sick in the whole course of their lives.

Another German version is recorded in 1857, this one from Switzerland, in Ernst Rochholz’s Alemannisches Kinderlied und Kinderspiel aus der Schweiz:

Ringel, Ringeli, Reihe,

d’ Chinde gönt i d’Maie.

sie tanzet um die Rosestöck

Und machet alle Bode-Bodehöck(Ring-a, ring-a, row,

The babes go into the greenwood.

They dance around the rosebush

And all squat down.)

An Italian version from Venice is recorded in 1874 by Giuseppe Bernoni:

Gira, gira, rosa,

Co la più bela in mezo;

Gira un bel giardino,

Un altro pochetino;

Un salterelo,

Un alto de più belo;

Una riverenza,

Un’altra per penitenza;

Un baso a chi ti vol.(Ring a ring a roses,

With the most beautiful in the middle;

Ring a pretty garden,

Another circle round,

A little skip,

Another even better,

A curtsy,

Another for penitence:

A kiss for the one you like.)

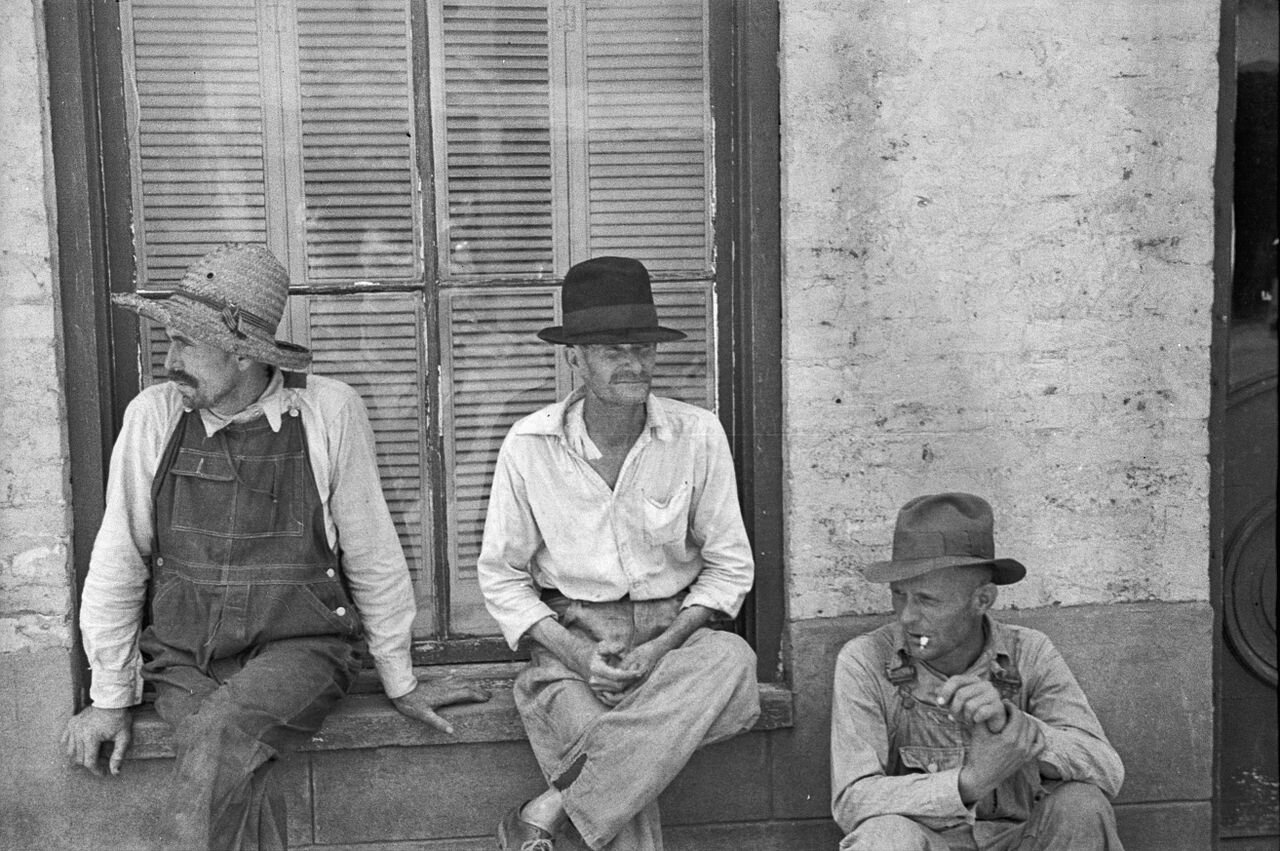

Kate Greenaway’s 1881 Mother Goose has this English version:

Ring-a-ring-a roses,

A pocket full of posies;

Hush! hush! hush! hush!

We’re all tumbled down.

Other English versions recorded by Newell in 1883 are:

Round the ring of roses,

Pots full of posies,

The one who stoops last

Shall tell whom she loves best.Ring around the rosie,

Squat among the posies.

Ring around the roses,

Pocket full of posies,

One, two, three—squat!A ring, a ring, a ransy,

Buttermilk and tansy,

Flower here and flower there,

And all—squat!

And there is this Parisian version also recorded in 1883 by E. Rolland:

A la main droite j’ai un rosier

Qui fleurira

Au mois de mai,

Au mois de mai,

Qui fleurira.

Entrez, entrez, charmante rose;

Embrassez celle que vous voudrez,

La rose

Ou bien le rosier(In my right hand I have a rosebush

Who will bloom

In May,

In May,

Who will bloom.

Come in, come in, lovely rose;

Kiss the one you want,

The rose

Or the rosebush)

Finally, we get this version from 1886, recorded in Charlotte Burne’s Shropshire Folk-Lore. It is one of the first to incorporate sneezing into the song. Burne’ writes:

Ring o’ roses. A ring, moving around, till the last line, when they stand and imitate sneezing.

Chorus. ‘A ring, a ring o’ roses,

A pocket-full o’ posies;

One for Jack and one for Jim and one for little Moses!

A-tisha! a-tisha! a-tisha!” COMMONAt Edgmond, where this game is a favorite with very little children, the last line runs, “A curchey in, and a curchey out, and curchey all together,” curtseying accordingly.

The reason for my including so many versions in different languages is because of the persistent false etymology that has attached to the rhyme. According to this tale, the nursery rhyme is a cultural memory of the plague—either the one of 1660 or even the Black Death of the fourteenth century. The tale is based on the canonical present-day version of the rhyme, which reads:

Ring around the rosie

A pocket full of posies

Ashes, ashes

We all fall down

Supposedly, ring around the rosie refers to buboes on the skin, a symptom of the bubonic plague. A pocket full of posies refers to flowers kept in the pocket to ward off the disease. Ashes, ashes is a reference to death, as in “ashes to ashes, dust to dust.” The common variant of the third line, Atishoo, atishoo, is a reference to sneezing and sickness. Finally, falling down is a representation of death.

But as we can see, this explanation does not work for the earliest known versions of the rhyme, which are clearly about picking flowers. And by focusing on one English version, the explanation ignores all the others, in all the other languages. Furthermore, the plague explanation itself doesn’t appear until the second half of the twentieth century. It is clearly an attempt to rationalize a rhyme that doesn’t make sense in our present-day culture, one where circular May Day dances are a thing of the past.

Sources:

Bernoni, Giuseppe. Giuochi Poplari Veneziani (Popular Venetian Games). Venice: Tipografia Melchiorre Fontana, 1874, 30. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Burne, Charlotte Sophia, ed. Shropshire Folk-Lore: A Sheaf of Gleanings, part 3. London: Trübner, 1886, 511–512. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Greenaway, Kate, illus. Mother Goose. London: Frederick Warne, 1881, 52. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Newell, William Wells, ed. Games and Songs of American Children. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1883, 127–28. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Opie, Iona and Peter. The Singing Game. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1988, 219–27. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, June 2010, modified June 2021, s.v. ring-a-ring o’ roses, n.

Rochholz, Ernst Ludwig. Alemannisches Kinderlied und Kinderspiel aus der Schweiz (German Children’s Songs and Games from Switzerland). Leipzig: J.J. Weber, 1857, 183. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Rolland, E. Rimes et Jeux de l’Enfance (Rhymes and Childhood Games). Les Littératures Populaires 14. Paris: Maisonneuve, 1883, 71–72. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Stephens, Ann S. The Old Homestead. New York: Bunce and Brother, 1855, 213–16. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Image credit: Kate Greenaway, 1881. Public domain image.