29 September 2021

In radio communications worldwide, the word roger is used to acknowledge receipt of a transmission. Roger stands for “received,” but why this particular word? Especially since the word in the standard spelling alphabet uses romeo for the letter < r >.

It turns out the choice is an arbitrary one that was made back in the 1920s, with the advent of voice transmissions over radio. When pronouncing letters, as when you spell out a word, the radio transmission can be garbled or indistinct. So various groups adopted spelling alphabets (often called phonetic alphabets, although that’s something of a misnomer) for use over radio. And in 1927, the US Navy adopted a spelling alphabet that used roger for the letter < r >:

Affirmative / Baker / Cast / Dog / Easy / Fox / George / Hypo / Interrogatory / Jig / King / Love / Mike / Negative / Option / Preparatory / Quack / Roger / Sail / Tare / Unit / Vice / William / X-ray / Yoke / Zed

This particular spelling alphabet was printed the Navy’s 1927 Bluejackets’ Manual alongside the corresponding flag and Morse code symbols for the letters, a neat moment in history when the three systems—flags, Morse code, and radio—were all in widespread use for communicating at sea.

By 1939, the US Army and Navy had developed a joint spelling alphabet for use by all the branches of service:

Affirm / Baker / Cast / Dog / Easy / Fox / George / Hypo / Inter / Jig / King / Love / Move / Negat / Option / Prep / Queen / Roger / Sail / Tare / Unit / Victor / William / Xray / Yoke / Zed

Use of roger in acknowledging receipt of a transmission is recorded by 1941, when it appeared in a list of such terms prepared by the US Army’s public relations division and reprinted in the journal American Speech:

ROGER! Expression used instead of okay or right. (Air Corps)

And roger as a verb meaning to acknowledge a transmission was recorded in civil aviation by August 1946 in a story about the airline business in Fortune magazine:

A pilot, bringing a ship into a major airport recently, checked with traffic control, reported his position at a range station, flying at 7,000 feet. Control told him: “Cleared to descend to 1,500 feet.” He rogered, descended, checked in again at 1,500 feet. This time ATC ordered: “Descend to 5,000 feet.” The hair rising on his neck, the pilot said he was already at 1,500 and why did they want him to hold at 5,000. ATC told him: “Other aircraft at 4,000 feet.” He had somehow descended safely through the other traffic in the fog.

In 1956, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and the military North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) adopted a spelling alphabet that dropped roger in favor of romeo. That alphabet is still in use:

Alfa / Bravo / Charlie / Delta / Echo / Foxtrot / Golf / Hotel / India / Juliet / Kilo / Lima / Mike / November / Oscar / Papa / Quebec / Romeo / Sierra / Tango / Uniform / Victor / Whiskey / X-ray / Yankee / Zulu

But despite the change, roger stayed on as the term for acknowledging messages.

Sources:

“Glossary of Army Slang.” American Speech, 16.3, October 1941, 168. JSTOR.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, November 2010, modified December 2020, s.v. roger, int. (and n.3); modified December 2019, s.v. roger, v.2.

US Army. FM 24-5, Basic Field Manual Signal Communication, 1 November 1939. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office 1939, § 181. Internet Archive.

US Navy. The Bluejackets’ Manual, seventh edition, revised (May 1927). Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office 1928, plates 4–6. ProQuest Congressional.

“What’s Wrong with the Airlines.” Fortune, August 1946, 192. EBSCOhost Fortune Archive.

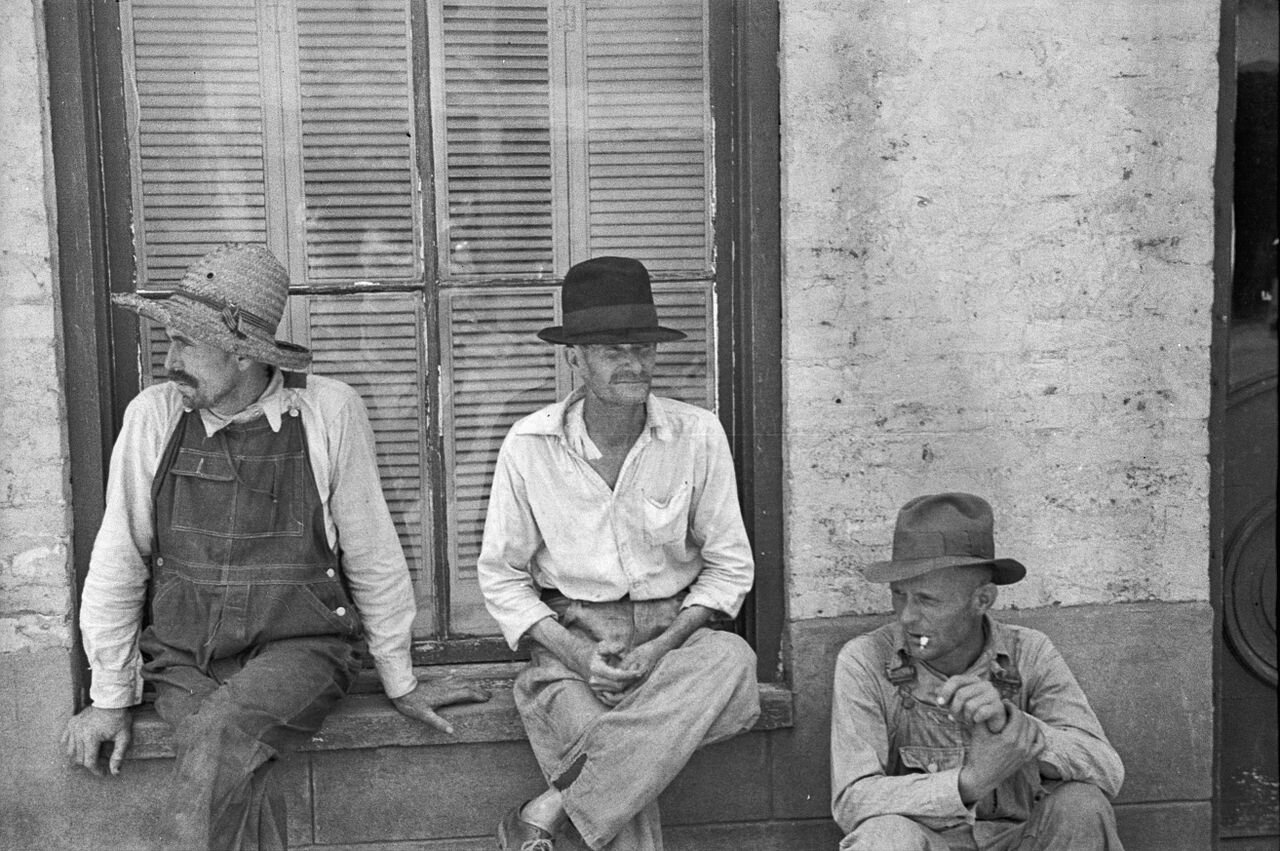

Image credit: Unknown artist, Office of War Information, July–August 1943. Library of Congress. Public domain Image.