12 October 2021

[Update, 13 October 2021: paragraph about Ode to a Scab added.]

A scab is the growth that covers a wound to the skin. It is also a slang term for a strikebreaker in a labor dispute. But how did the word develop such different meanings?

Scab is from the Old English sceabb, which referred to a variety of skin diseases, including but not exclusively leprosy. In two old entries, the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) splits the word into two, with shab coming from the Old English, and scab coming from an unattested Old Norse root, *skabbr. But the OED immediately calls this etymology into question. Not only is the Old Norse root unattested, but the earliest citation of the scab form is in a thirteenth-century Kentish dialect, and that dialect did not have significant Old Norse influence. It seems more likely the older OED entries are incorrect, and scab and shab are different forms of the same word, with the later scab form being influenced by the Latin scabies.

An example of the Old English is from the translation of Gregory the Great’s Pastoral Care, written in the late ninth century:

Soðlice se hæfð singalne sceabb se þe næfre ne blinð ungestæððignesse. Ðonne bi ðæm sceabbe swiðe ryhte sio hreofl getacnað ðæt wohhæmed. And ðonne bið se lichoma hreof, ðonne se bryne þe on ðæm innoðe bið utaflihð to ðære hyde. Swæ bið sio costung ærest on ðæm mode, & ðonne færeð utweardes to ðære hyde, oððæt hio utascieð on weorc.

(Truly, he has chronic scabbiness who never desists from sin. Then by the scabs very directly the scurf symbolizes that fornication. And when the body is scurfy, then the inflammation that is inside spreads to the skin. So is the temptation first in the mind, and then travels outward to the skin, until it bursts forth in action.)

The aforementioned thirteenth-century Kentish source is from a sermon:

Se leprus signefiez þo senuulle men. si lepre þo sennen. Þet scab bi tokned þo litle sennen. si lepre be tokned þo grete sennen þet biedh diadliche. Ase so is lecherie. spusbreche. Gauelinge. Roberie. þefte. Glutunie. drunkenesse. and alle þo sennen þurch wiche me liest þo luue of gode almichti and of alle his haleghen.

(The leprous signify the sinful men. The leprosy is their sins. That scab symbolizes their little sins. The leprosy symbolized their great sins that are deadly. So, leprosy is spouse-breaking, usury, robbery, theft, gluttony, drunkenness, and all those sins through which one loses the love of God almighty and all his saints.)

Note that in both these early uses, scab refers to a skin disease, and it’s metaphorically associated with sinfulness and bad action. The sense of scab referring to the growth that covers a wound to the skin appears by the late fourteenth century. It appears in a c.1380 translation of Lanfranc of Milan’s treatise on surgery in a section about how to heal ulcers of leprosy and ringworm:

If þere ben pustulis þat ben hote & ful of blood, & þe skyn be ful of humouris & neische, þanne it is good for to garce þat skyn, & þanne waische al his heed with þat blood hoot, & þanne hile his heed wiþ caule leuis. þanne aftirward anoynte al his heed wiþ oile of notis ouþer of camomil hoot, til al þe scabbis þerof be wel tobroke. & þanne bigynne for to drie with þese driynge medicyns.

(If there are pustules that are hot and full of blood, and the skin is full of humors and tender, then it is good to cut that skin and then wash all his head with that hot blood, and then heal his head with kale leaves. Then afterward anoint all his head with oil of nuts or hot camomile, till all the scabs thereof are well broken open. And then begin to dry with these drying medicines.)

By the late sixteenth century, a slang sense of scab had developed, meaning a scoundrel or low person. Skin diseases are not pleasant, and as we have seen, have been associated with bad behavior from the beginning, so it’s easy to see how the leap was made from the medical conditions to low character. We see this slang sense in Robert Wilson’s 1590 play The Three Lords and Three Ladies of London. In the play, three lords and their pages, Policy (page Wit), Pomp (page Wealth), and Pleasure (page Will) debate which of three London women is the right match for Policy:

Pom[pe]. Whom louest thou pleasure?

Plea[sure]. Hearke ye. Whisper in his eare.

Pom[pe]. Lush, ye lie.

Wil. If my maister were a souldier, that word wold haue the stab.

Wit. Wel Wil, stil you'll be a saucie Scab.

This use was likely preceded by John Lyly’s use of the slang sense of scab in his play Endymion. The play was probably written in the 1580s, but was not published until 1591. Furthermore, the 1591 printing omits the portion that includes scab. The word appears in a song that ends Act 4, Scene 2, but the song is mentioned as a stage direction, but the words are not reproduced in that early printing. The song isn’t printed until a 1632 edition:

Watch[men]. Stand! Who goes there?

We charge you appeare

Fore our Constable here.

(In the name of the Man in the Moon)

To vs Bilmen relate,

Why you stagger so late.

And how you come drunke so soone.Pages. What are yee (scabs?)

Watch. The Watch:

This the Constable.Pages. A Patch.

Const. Knockʼem down unlesse they all stand

If any run away,

Tis the old Watchmans play,

To reach him a Bill of his hand.

We cannot know if scab appeared in the Lyly’s original version of the play. The song lyrics may have changed between the 1580s and 1632.

The sense of a low, disreputable person is applied to strikebreakers in labor disputes by the latter half of the eighteenth century. The OED has this citation from Bonner & Middleton’s Bristol Journal of 5 July 1777:

To the Public. Whereas the Master Cordwainers have gloried, that there has been a Demur amongst the Men's and Women's Men;—we have the Pleasure to inform them, that Matters are amicably settled. [...] The Conflict would not been [sic] so sharp had not there been so many dirty Scabs; no Doubt but timely Notice will be taken of them.

And another early use of the strikebreaker sense appears in the Articles of the Friendly and United Society of Cordwainers (shoemakers) of 4 June 1792:

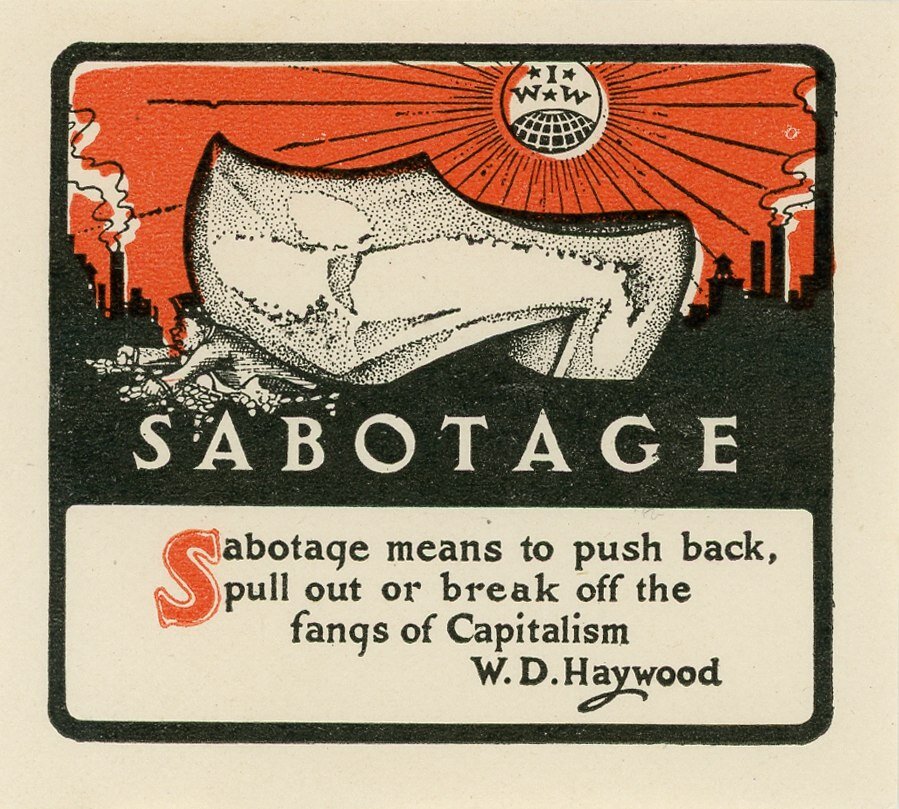

Some of the Articles make mention of scabs. And what is a scab? He is to his trade what a traitor is to his country; though both may be useful to one party in troublesome times, when peace returns they are detested alike by all. When help is wanted, he is the last to contribute assistance, and the first to grasp a benefit he never laboured to procure. He cares but for himself, but he sees not beyond the extent of a day, and for a momentary and worthless approbation, would betray friends, family and country. In short, he is a traitor on a small scale. He first sells the journeymen, and is himself afterwards sold in his turn by the masters, till at last he is despised by both and deserted by all. He is an enemy to himself, to the present age and to posterity.

That’s how pustules on the skin were transformed into strikebreakers.

Note: a piece titled Ode to a Scab, about strikebreakers, is frequently credited to Jack London, but there is no evidence that he wrote it. The piece dates to at least 1912, when it is circulated anonymously in a number of trade-union journals. London’s name becomes attached to it by 1950, long after the writer’s death.

Sources:

Aspinall, A., ed. “Articles of the Friendly and United Society of Cordwainers” (4 June 1792). Early English Trade Unions. London: Batchworth Press, 1949, 84. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Fleischhaker, Robert, ed. Lanfrank’s “Science of Cirurgie.” Early English Text Society OS 102. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, 1894, 185. HathiTrust Digital Archive. Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ashmole MS 1396.

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, 2021, s.v. scab, n.1.

Hall, Joseph. “Dominica tercia post octavam epiphanie” (The Third Sunday After the Eighth Epiphany). Selections from Early Middle English 1130–1250, vol. 1 of 2. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1920, 218. HathiTrust Digital Archive. Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Laud Misc. 471.

Latham, R.E., D.R. Howlett, and R.K. Ashdowne. Dictionary of Medieval Latin from British Sources. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2013, s.v. scabies. Brepols: Database of Latin Dictionaries.

Lewis, Charlton T. and Charles Short. A Latin Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1879, s.v. scabies. Brepols: Database of Latin Dictionaries.

Lyly, John. Endimion, The Man in the Moone. London: I. Charlewood for the Widow Broome, 1591, sig. G2r. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

———. “Endimion.” Sixe Court Comedies. London: William Stansby for Edward Blount, 1632, sig. E2r–v. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Middle English Dictionary, 2019, s.v. scab(be n.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. scab, n., shab, n.

Sweet, Henry, ed. King Alfred’s West-Saxon Version of Gregory’s Pastoral Care, vol. 1 of 2. Early English Text Society OS 45. London: N. Trübner, 1871, 70. HathiTrust Digital Archive. London, British Library, MS Cotton Tiberius B.11.

Wilson, Robert. The Pleasant and Stately Morall, of the Three Lordes and Three Ladies of London. London: R. Jhones, 1590, sig. Bv. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

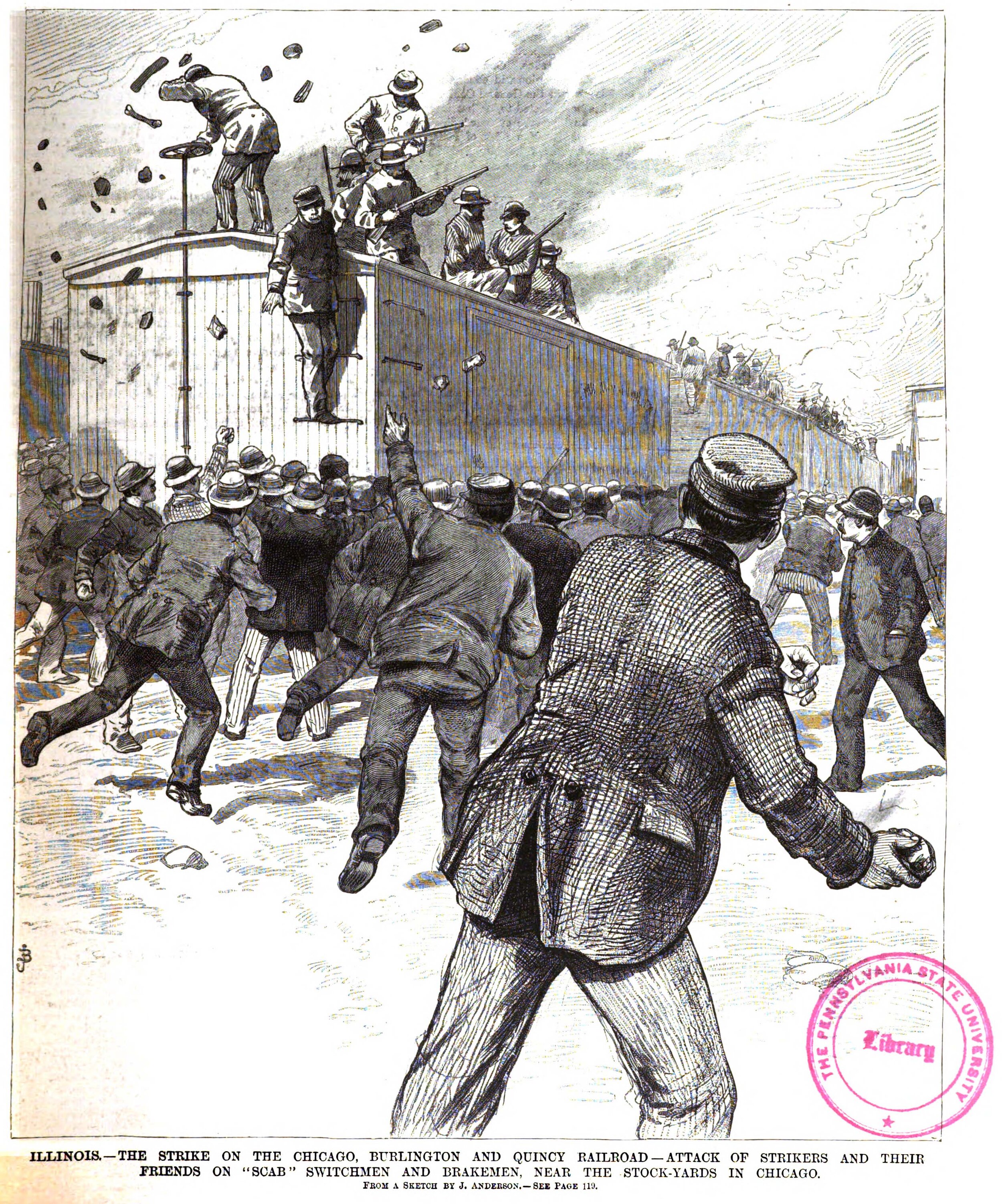

Image credit: J. Anderson, 1888. In Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 7 April 1888. HathiTrust Digital Archive. Public Domain Image.