27 October 2021

The origin of the word shark is a mystery. It was in use by sailors in the fifteenth century and entered into the general vocabulary by the mid sixteenth century, but where and from what language the sailors acquired the word is just not known.

Thomas Beckington, secretary to King Henry VI and Bishop of Bath and Wells, was the first known Englishman to record the word shark. He used it in the 11 July 1442 entry in his journal, which is written in Latin:

In mare contigebat le calm, et circiter horam vijam in sero per æstimationem navem sequebatur piscis vocatus le Shark, qui quidem piscis percutiebatur bis cum uno harpingyren et recessit; quibus vero percussionibus non obstantibus incessanter navem sequebatur; et tunc magister navis cum dicto ferro latera ejus penetravit.

(It happened in a calm sea, and late in the day, at about the seventh hour by estimation, a fish called the shark gave chase to the ship, which indeed was struck twice with one harpoon and it retreated; which truly, notwithstanding the blows, incessantly pursued the ship, until the master of the ship pierced its sides with the said iron.)

Since the definite article le does not exist in classical Latin and given that Beckington was crossing to Bordeaux, one might think the word has a French origin. But le is common in medieval Anglo-Latin. There is nothing here that tells us of the word’s origin, except that the fish was being called that by sailors in 1442. And since sailors on board a ship might come from an assortment of countries, we can’t even draw a conclusion about their nationality or native language.

The Beckington use, however, is an isolated appearance. Shark does not start to be used in print with any frequency until more than a century later, indicating that it was sailor jargon that had not yet penetrated into the general vocabulary.

The next appearance of shark in English is in a broadside advertisement for a large specimen of the fish that was on display in London in June 1559:

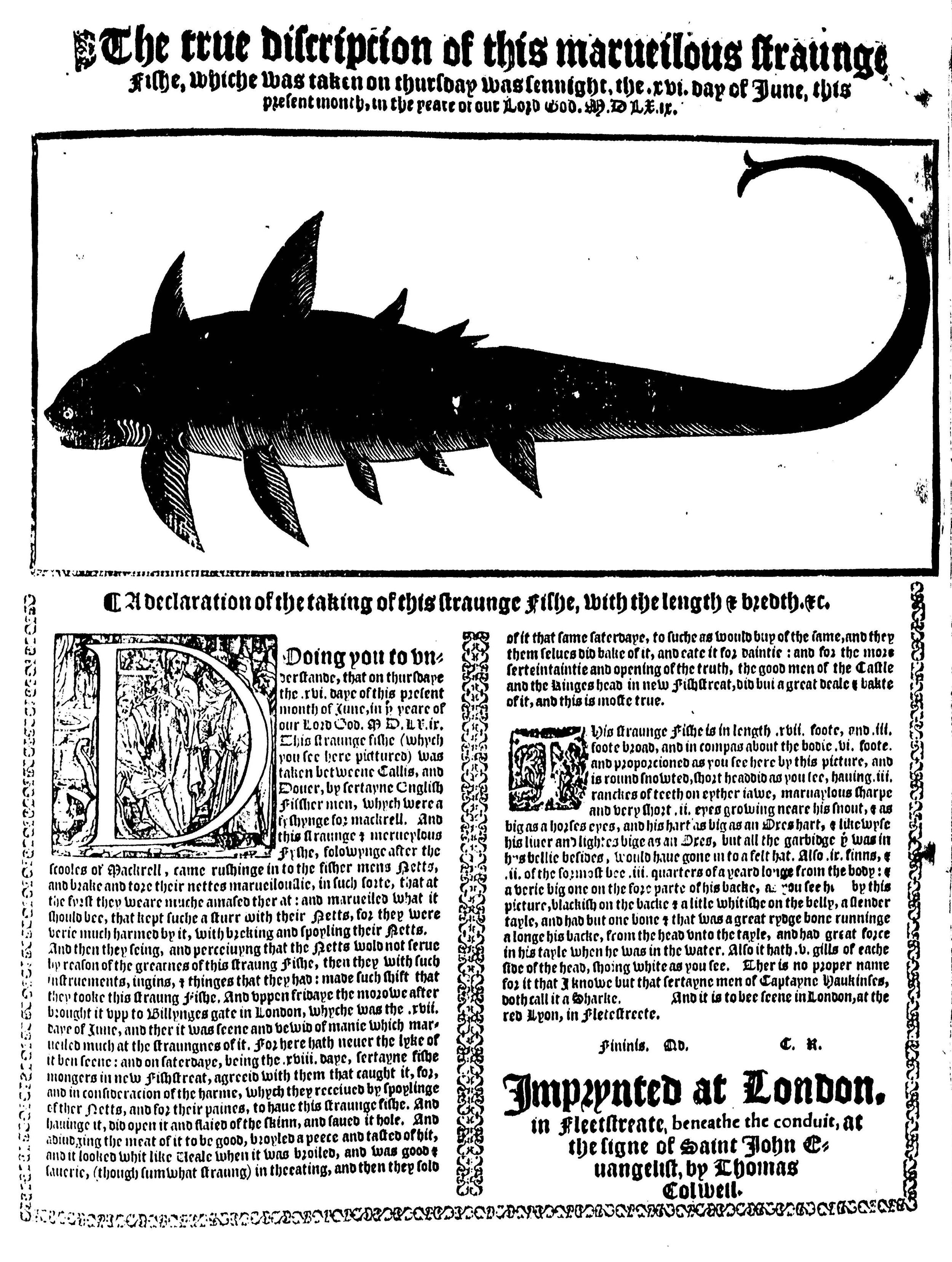

The True Discription of this Marueilous Straunge Fishe, whiche was taken on Thursday was sennight, the xvj. day of June, this present month, in the yeare of our Lord God, M.D.lxix.

A declaration of the taking of this straunge Fishe, with the lengthe and bredth, &c.

DOOING you to vnderstande that on Thursdaye, the xyj. daye of this present month of June, in the yeare of our Lord God M.D.lxix. this straunge fishe was taken betweene Callis and Douer, by sertayne English fissher-men whych were a fyshynge for mackrell. And this straunge and merueylous fyshe, folowynge after the scooles of mackrell, came rushinge in to the fisher-mens netts, and brake and tore their nettes marueilouslie, in such sorte, that at the fyrst they weare muche amased therat, and marueiled what it should bee that kept suche a sturr with their netts, for they were verie much harmed by it with breking and spoyling their netts.

And then they, seing and perceiuyng that the netts wold not serue, by reason of the greatnes of this straung fishe, then they with such instruements, ingins, and thinges that they had, made such shift that they tooke this straung fishe. And vppon Fridaye, the morowe after, brought it vpp to Billyngesgate in London, whyche was the xvij. daye of June, and ther it was seene and vewid of manie, which marueiled much at the straungnes of it; for here hath neuer the lyke of it ben seene: and on Saterdaye, being the xviij. daye, sertayne fishe-mongers in New Fishstreat agreeid with them that caught it, for and in consideracion of the harme whych they receiued by spoylinge of ther netts, and for their paines, to haue this straunge ; fishe. And hauinge it, did open it and flaied of the skinn, and saued it hole. And, adiudging the meat of it to be good, broyled a peece and tafted of hit, and it looked whit like veale when it was broiled, and was good and sauerie (though sumwhat straung) in the eating, and then they sold of it that same Saterdaye to suche as would buy of the same, and they themselues did bake of it, and eate it for daintie ; and for the more sertaintie and opening of the truth, the good men of the Castle and the Kinges Head in new Fishstreat did bui a great deale and bakte of it, and this is moste true.

The straunge fishe is in length xvij. foote and iij. foote broad, and in compas about the bodie vj. foote; and is round snowted, short headdid, hauing iij. ranckes of teeth on eyther iawe, maruaylous sharpe and very short, ij. eyes growing neare his shout, and as big as a horses eyes, and his hart as big as an oxes hart, and likewyse his liuer and lightes bige as an oxes; but all the garbidge that was in hys bellie besides would haue gone into a felt hat. Also ix. finns, and ij. of the formost bee iij. quarters of a yeard longe from the body, and a verie big one on the fore parte of his backe, blackish on the backe, and a litle whitishe on the belly, a slender tayle, and had but one bone, and that was a great rydge-bone, runninge a-longe his backe from the head vnto the tayle, and had great force in his tayle when he was in the water. Also it hath v. gills of eache side of the head, shoing white. There is no proper name for it that I knowe, but that sertayne men of Captain Haukinses doth call it a sharke. And it is to bee seene in London, at the Red Lyon in Fletestreete.

Finis, quod C.R.

Imprynted at London, in Fleetstreate, beneathe the Conduit, at the signe of Saint John Euangelist, by Thomas Colwell.

The Oxford English Dictionary, in an older entry, errs in stating the fish was captured and brought back by John Hawkins’s expedition. The broadside clearly states that the shark had been captured by mackerel fishermen that very June. Hawkins’s third voyage had ended several months earlier, in January 1568/69. The only connection to Hawkins is that a sailor from his expedition had identified the fish caught by the mackerel-men as a shark.

This display of the shark was quite famous in its day. In The Tempest (1611), Shakespeare apparently alludes to it and to the exhibition of Indigenous people captured in the Americas and brought back to England for profit. In scene 2.2, Trinculo comes upon the sleeping Caliban and discusses taking him back to London and exhibiting him for money:

What haue we here, a man or a fish? dead or aliue? a fish, hee smels like a fish: a very ancient and fish-like smell: a kinde of, not of the newest poore-John: a strange fish: were I in England now (as I once was) and had but this fish painted; not a holiday-foole there but would giue a peece of siluer: there, would this Monster, make a man: any strange beast there makes a man: when they will not giue a doit to relieue a lame Beggar, they will lay out ten to see a dead Indian.

The application of shark to predatory humans comes first as a verb. The verb to shark appears in Sir Thomas More, an Elizabethan play. The play is from c.1592, with later revisions. In the past mistakenly attributed to Shakespeare, the play is the product of a collaborative effort. The manuscript is composed by six different hands, and attribution of authorship is contentious. It may, however, been originally composed by Anthony Munday and Henry Chettle, and later, after 1600, revised by Thomas Heywood and Thomas Dekker. The fifth hand is that of a theater scribe who seems to have supervised the revision process but was apparently not a substantial contributor to original text. The sixth hand, contributing a single scene, has tenuously been identified as Shakespeare’s, but if it is his, it’s unclear whether the scene he contributed was to the original text or the revision. The passage with shark, which is not in the scene thought to be by Shakespeare, is as follows:

What had you gott? I’le tell you: you had taught

How insolence and strong hand shoold prevayle,

How ordere shoold be quelld; and by this patterne

Not on of you shoold lyve an aged man,

For other ruffians, as their fancies wrought,

With sealf same hand, sealf resons, and sealf right,

Woold shark on you, and men lyke ravenous fishes

Woold feed on on another.

The use of the noun shark to refer to a predatory human is from the same period and also from the stage. This sense first appears in the dramatis personae of Ben Jonson’s 1600 play The Comicall Satyre of Euery Man Out of his Humour. Jonson uses the phrase thredbare shark to describe a character named Shift:

SHIFT.

A Thredbare Sharke. One that neuer was Soldior, yet liues vpon lendings. His profession is skeldring and odling, his Banke Poules, and his Ware-house Pict-hatch. Takes vp single Testons vpon Oths till dooms day. Fals vnder Executions of three shillings, & enters into fiue groat Bonds. He way-layes the reports of seruices, and cons them without booke, damming himselfe be came new from them, when all the while hee was taking the diet in a bawdie house, or lay pawn'd in his chamber for rent and victuals. Hee is of that admirable and happie Memorie, that hee will salute one for an old acquaintance, that hee neuer saw in his life before. Hee vsurps vpon Cheats, Quarrels, & Robberies, which he neuer did, only to get him a name. His cheef exercises are taking the Whiffe, squiring a Cocatrice, and making priuie searches for Imparters.

The use of the shark to refer to people was also probably influenced by the German Schurke, meaning a cheat or scoundrel. The passage in Sir Thomas More clearly refers to the fish, but this appearance could be a double entendre, combining both the predatory fish and scoundrel meanings.

Discuss this post