26 January 2022

A peanut is the seed of the legume Arachis hypogaea. The name is a compound of pea + nut, presumably because it resembles the seed pod of the pea, but the seed itself is harder, like a nut. (Botanically, it’s not technically a nut.) The plant is native to South America but is commercially grown in warmer climes throughout the globe. In addition to being the name of the legume, peanut has developed a slang sense for things and people who are physically small or socially insignificant, such as children.

The name peanut dates to the early nineteenth century, although there is at least one late eighteenth century use of the word to refer to the hickory nut. The hickory nut usage is from Henry Wansey’s 1796 Journal of an Excursion to the United States:

I brought from the United States with me, of live animals, two kinds of tortoises, and a beautiful flying squirrel; of shrubs and plants, rhododendrons, martegon lillies, tulip trees, acacias, Virginia cypresses, magnolia glaucus, sugar maple trees, &c. Of nuts, hiccory and chinquopin, or pea nuts. The latter, I find, is very common in China, as a native Chinese told me, when dining at my house, with two gentlemen of Lord Macartney’s suite, some of those nuts being on table.

The earliest known use of peanut to refer to the legume is by Washington Irving in one of the letters of Jonathan Oldstyle, first published in the New York Morning Chronicle of 1 December 1802:

The curtain rose—out walked the Queen with great majesty; she answered my ideas—she was dressed well, she looked well, and she acted well. The Queen was followed by a pretty gentleman, who, from his winking and grinning, I took to be the court fool; I soon found out my mistake. He was a courtier “high in trust,” and either general, colonel, or something of martial dignity. They talked for some time, though I could not understand the drift of their discourse, so I amused myself with eating pea-nuts.

Within a few decades, however, peanut had acquired an adjectival use meaning small, insignificant, or foolish. From William Dunlap’s 1836 Thirty Years Ago; or the Memoirs of a Water Drinker, in which the character Spiff describes an encounter with some hecklers in a theater where his wife is performing as Lady Macbeth:

“Two blackguards came into the Shakespeare box and disturbed the audience while Mrs. Spiffard was in one of her best scenes; and the scoundrels made use of insolent language respecting her—her person—her acting—and I think I can appeal to any one in favour of her Lady Macbeth at all times.”

[...]

“But you, Spiff, when they insulted Mrs. Spiffard?—What said you” asked the manager.

“‘This may be sport,” said I, ‘to you, but it is a serious injury—a wanton outrage upon the feelings of the audience and the actor or actress.’”

[...]

“Well. What said they.”

“They look’d at each other, and then at me, as much to say, ‘who are you?’—I answered that look——”

“With a look?”

“‘I am that lady’s husband.’ They look’d at each other again—appeared to feel like fools by quitting their places, for they were standing on the seats of the box, and soon after they shuffled off, as well as they could.”

“And left you ‘cock of the walk,’ as Millstone says.”

“We ought all to thank you,” said Cooper, “they were your pea-nut fellows, I suppose.”

Within a few decades this adjective meaning insignificant had morphed into a noun. From an 1864 account by Mark Twain:

I observe that that young officer of the Pacific squadron—the one with his nostrils turned up like port-holes—has become a great favorite with half the mothers in the house, by imparting to them much useful information concerning the manner of doctoring children among the South American savages. His brother is a brigadier in the Navy. The drab-complexioned youth with the Solferino mustache has corralled the other half with the Japanese treatment.—The more I think of it, the more I admire it. Now, I am no peanut. I have an idea that I could invent some little remedies that would stir up a commotion among these women, if I chose to try. I always had a good general notion of physic, I believe. It is one of my natural gifts, too, for I have never studied a single day under a regular physician. I will jot down a few items here, just to see how likely I am to succeed.

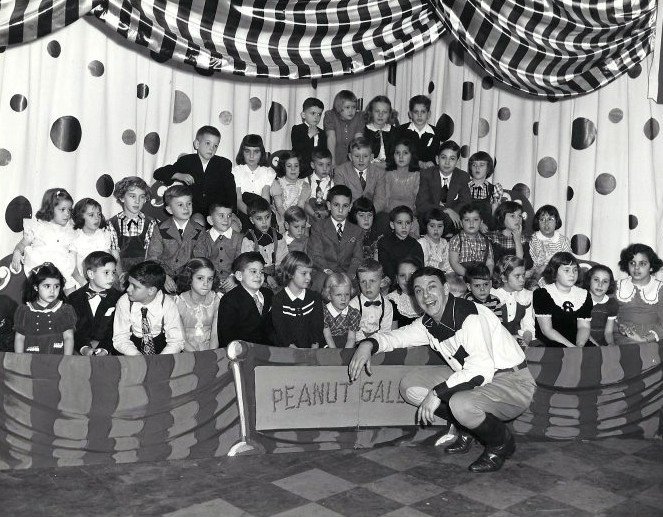

This nominal use to mean a small or insignificant person would evolve into a sense of peanut meaning a child, a sense that would often be used affectionately. This last is, perhaps, most famously exemplified by Charles Schulz’s long-running comic strip Peanuts.

And around the same time that Twain was writing the above piece, the term peanut gallery came into use, referring to the cheap seats in a theater, usually the highest balcony. Because the seats were inexpensive, they were often occupied by a rowdy and boisterous crowd. In the American South, however, peanut gallery referred to the segregated seats occupied by Blacks. Here is an 1867 example from the New Orleans Times Picayune in a review of a performance by blackface minstrels:

It is useless for us to repeat our praises of Johnny Thompson, Billy Reeves, and others of the company, as negro delineators; they “out Herod Herod,” and put the darkies in the “peanut gallery” fairly to the blush.

An early, non-racialized use of peanut gallery can be found the Placerville, California Mountain Democrat of 10 June 1876. Republican senator and presidential candidate James G. Blaine had been accused of selling worthless land to the Union Pacific Railroad, a laundering of bribe money. This passage details Blaine’s attempt to divert attention away from the scandal. Blaine would lose the nomination fight to Rutherford B. Hayes:

The emergency demanded a bold and prompt diversion. So this modern Scipio for the second time this session “carried the war into Africa,” sprang into the House with his bundle of letters, read them in an excited manner to an excited audience, giving plausible explanations as he went along, winding up with a savage assault upon J. Proctor Knott, Democratic Chairman of the Judiciary Committee. There was a great deal of Beecherism in all this. It was bold, brilliant, adroit, audacious. As a bid for applause from the political pit and peanut gallery it was a masterpiece.

Some sources contend that peanut gallery comes from the practice of people in the cheap seats eating peanuts, but it is more likely that it is simply an outgrowth of the small, insignificant sense. Those in the cheap seats, whether they be Black people; children; or boisterous, white adults didn’t matter.

And for an extensive review of the names for the peanut in different languages, see the Polyglot Vegetarian: “Peanut” and “Peanut, Continued.”

Sources:

Dunlap, William. Thirty Years Ago; or the Memoirs of a Water Drinker, vol. 2 of 2. New York: Bancroft and Holley, 1836, 25.

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, 2021, s.v. peanut, n., peanut, adj.

Irving, Washington. “Letter 2” (1 December 1802). Letters of Jonathan Oldstyle. New York: William H. Clayton, 1824, 11–12. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

“The Modern Scipio.” Mountain Democrat (Placerville, California), 10 June 1876, 2. NewspaperArchive.com.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, September 2005, modified December 2021, s.v. peanut, n. and adj.

Times-Picayune (New Orleans), 16 January 1867, 2. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Twain, Mark (Samuel Clemens). “Those Blasted Children” (1864). Mark Twain’s San Francisco, Bernard Taper, ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1963, 31. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Wansey, Henry. The Journal of an Excursion to the United States of North America in the Summer of 1794. Salisbury: J. Easton, 1796, 250. Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO).

Photo credit. Unknown photographer, 1940s–50s, NBC Television. Public domain image in the United States as it was published in the United States between 1926–77 without a copyright notice.