13 July 2022

(Updated 14 July 2022 with a reference to the 1899 play of Tale of Two Cities)

Like most slang terms, the origin of twenty-three skidoo is not known for certain, but we do have some clues that give us a probable answer. Twenty-three skidoo, which appears in the opening years of the twentieth century, can be a noun, exclamation, or verb referring to leaving, departure, or making an exit, particularly a rapid one. The phrase is actually a combination of two other slang terms, both of them meaning the same as the combined phrase.

The phrase has engendered a number of mythical explanations, but here is what we actually know. Twenty-three skidoo makes its appearance in the opening years of the twentieth century, first seeing print in 1906, but being somewhat older in speech. The individual elements, twenty-three and skidoo, are older still. Skidoo is probably a variation on skedaddle, but the twenty-three element is more uncertain. The most likely, but by no means certain, origin is in a particular con game, as explained in Will Irwin’s 1909 Confessions of a Con Man:

We had two shell games, a “cloth” and a “roll-out” team. I don’t have to explain the shell game, I guess. “Cloth” is an easy-money dice game. The operator has before him a sheet of green felt, marked off into figured squares—eight to forty-eight. The player throws eight dice, and the dealer compares the sum of the spots he has thrown with the numbers on the cloth. Certain spaces are marked for prizes, five or six are marked “conditional,” and one, number twenty-three, is marked “lose.” The dealer keeps his stack of coins over the twenty-three space, so that it isn't noticed until the time to show it.

WHY TWENTY-THREE MEANS DOWN AND OUT

These spaces marked “conditional” are used in a great many gambling games, such as spindle; they're the most useful thing in the world for leading the sucker on. For when he throws “conditional,” the dealer tells him that he is in great luck. He has thrown better than a winning number. He has only to double his bet, and on the next throw he will get four times the indicated prize, or if he throws a blank number, the equivalent of his money. He is kept throwing “conditionals” until his whole pile is down; and then made to throw twenty-three—the space which he failed to notice, and which is marked “lose.”

You may ask how the dealer makes the sucker throw just what he wants. Simplest thing in the world. The man is counted out. The table is crowded with boosters, all jostling and reaching for the box, eager to play. The assistant dealer grabs up the dice, adds them hurriedly, announces the number that he wants to announce, and sweeps them back into the box. If the sucker kicks, a booster reaches over next time the dice are counted, says “my play,” and musses them up. The player never knows what he has thrown. I don’t need to say that “twenty-three,” as slang, comes from this game. The circus used it for years before it was ever heard on Broadway.

While there is no direct evidence to support this story, all the elements ring true. One well-established route for slang is bubbling up from the criminal element, and many other slang terms had circulated for several decades in a particular underworld class before becoming known to the general public.

Twenty-three, used to indicate a departure, is recorded at the end of the nineteenth century. It appears in an article in Lexington, Kentucky’s Morning Herald on 17 March 1899, and the includes the first of our mythical explanations:

TWENTY-THREE

Did the Slang Phrase Originate in Dickens’ “Tale of Two Cities?”

For some time past there has been going the rounds of the men about town the slang phrase “Twenty-three.” The meaning attached to it is to “move on,” “get out,” “goody-bye, glad you are gone,” “your move” and so on. To the initiated it is used with effect in a jocular manner.

It has only a significance to local men and is not in vogue elsewhere. Such expressions often obtain a national use, as instanced by “rats!” “cheese it,” etc., which were once in use throughout the length and breadth of the land.

Such phrases originated, no one can say when. It is ventured that this expression originated with Charles Dickens in the “Tale of two [sic] Cities.” Though the significance is distorted from its first use, it may be traced. The phrase “Twenty-three” is in a sentence in the close of that powerful novel. Sidney Carton, the hero of the novel, goes to the guillotine in place of Charles Darnay, the husband of the woman he loves. The time is during the French Revolution, when prisoners were guillotined by the hundred. The prisoners are beheaded according to their number. Twenty-two has gone and Sidney Carton answers to—Twenty-three. His career is ended and he passes from view.

This origin is plausible on its face but seems unlikely. Slang terms rarely spring from decades-old literary works. Yet, the number does feature in the closing chapters of Dickens’s novel. After the protagonist, Sydney Carton, masquerading as Charles Darney, is sentenced to the guillotine, he is assigned to be the twenty-third person executed on that day:

There were twenty-three names, but only twenty were responded to; for one of the prisoners so summoned had died in gaol and been forgotten, and two had already been guillotined and forgotten. The list was read, in the vaulted chamber where Darnay had seen the associated prisoners on the night of his arrival. Every one of those had perished in the massacre; every human creature he had since cared for and parted with, had died on the scaffold.

And as he goes to the gallows:

She kisses his lips; he kisses hers; they solemnly bless each other. The spare hand does not tremble as he releases it; nothing worse than a sweet, bright constancy is in the patient face. She goes next before him—is gone; the knitting-women count Twenty-Two.

“I am the Resurrection and the Life, saith the Lord: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live: and whosoever liveth and believeth in me shall never die.”

The murmuring of many voices, the upturning of many faces, the pressing on of many footsteps in the outskirts of the crowd, so that it swells forward in a mass, like one great heave of water, all flashes away. Twenty-Three.

Some cite a production of a play based on the novel that opened in New York City in September 1899. The production’s final scene used a prominent the counting of the number of those sent to the guillotine to add suspense to the show. But as the Kentucky Morning Herald article predates the production by several months, it’s clear that the play is not the origin of twenty-three or even of the myth that it is connected to Dickens’s novel. We can’t, therefore, declare this explanation to be impossible, just improbable.

A few months later, an article in the 22 October edition of the Washington Post postulates a different, equally unlikely origin. In the article, writer George Ade, who had recently published his Fables in Slang has this to say about twenty-three:

By the way, I have come upon a new piece of slang within the past two months and it has puzzled me. I just heard it from a big newsboy who had a “stand” on a corner. A small boy with several papers under his arm had edged up until he was trespassing on the territory of the other. When the big boy saw the small one he went at him in a threatening manner and said: “Here! Here! Twenty-three! Twenty-three!” The small boy scowled and talked under his breath, but he moved away. A few days after that I saw a street beggar approach a well-dressed man, who might have been a bookmaker or horseman, and try for the unusual “touch.”

This man looked at the beggar in cold disgust and said: “Aw, twenty-three!” I could see that the beggar didn’t understand it any better than I did. I happened to meet a man who tries to “keep up” on slang and I asked the meaning of “Twenty-three!” He said it was a signal to clear out, run, get away. In his opinion it came from the English race tracks, twenty-three being the limit on the number of horses allowed to start in one race. This was his explanation. I don't know that twenty-three is the limit. But his theory was that “twenty-three” means that there was no longer any reason for waiting at the post. It was a signal to run, a synonym for the Bowery boys’ “On your way!” Another student of slang said the expression originated in New Orleans at the time that an attempt was made to rescue a Mexican embezzler who had been arrested there and was to be taken back to his own country. Several of his friends planned to close in upon the officer and prisoner as they were passing in front of a business block which had a wide corridor running through to another block. They were to separate the officer from the prisoner and then, when one of them shouted “Twenty-three,” the crowd was to scatter in all directions, and the prisoner was to run back through the corridor, on the chance that the officer would be too confused to follow the right man. The plan was tried and it failed, but “twenty-three” came into local use as meaning “Get away, quick!” and in time it spread to other cities. I don't vouch for either of these explanations. But I do know that “twenty-three” is now a part of the slangy boys’ vocabulary.

In this case, however, we can safely discount English horseracing as being the origin. Not only is the term distinctly American slang, a perusal of late nineteenth-century British racing papers shows that there was no set number of entrants in a race; the number varied greatly from race to race, not infrequently exceeding twenty-three. Nor does the New Orleans story have any evidence to support it. Besides being so vague on the details that one cannot verify it, it is deeply unsatisfying because it doesn’t explain why that number was chosen. If the incident did occur, it would seem the ruffians were using a term that was already in use and known to the criminal element, which would hint at the con game origin.

As for skidoo, that word is first recorded in 1904. From the Los Angeles Times of 25 December 1904:

A pair of touts wearily leaned against one of the deserted betting boxes in the big Ascot betting ring just before yesterday’s third race. One was lazily blowing cigarette wreaths. Both were knocking the game like a pair of pile drivers. Quoth the first:

“Aw go on. These guys are all wise. I start to squeak at some rummy-looking duck, an’ he turns on me, squints, and says: ‘Skidoo for you, pal—get a live one.’”

As for the combined phrase, that starts appearing in print like gangbusters in 1906 in papers across the United States. The two elements are collocated in a poem published by the Charleston, South Carolina Sunday News on 4 February 1906:

They ain’t no bitter tears to shed;

They ain’t no farewell song to glee;

They won’t be anybody dead

Of grief when I have “twenty-three.”

Skidoo, skidoo, for me and mine;

The great big world has tipped the sign,

Done got to go and look at it—

So—I done quit.

This isn’t a use of the phrase, per se, but it does place the words next to one another and in the right order. By collocating the words, the poet may be alluding to the combined phrase because a few months later we see the combined phrase used in an advertisement for moth balls in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle of 1 April 1906:

Moths, 23.Skidoo!

Moth Balls 3 lbs. for 10c

And two days later this mysterious one-line notice appears in Indiana’s Muncie Morning Star:

Dowie in case he returns to Zion City will have to reside at No. 23 Skidoo street.

Evidently, Zion City is an old nickname for Muncie.

And a few weeks after that there is another appearance in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, this time in the sports pages. A 19 April 1906 article about the Brooklyn baseball team, then known officially as the Superbas (the Dodgers nickname was unofficial at the time) has this to say:

It looks as if the privilege of having “World’s Champions” printed across their chests gives to the Giants the right to question every decision, surround the umpires and otherwise boss things to suit themselves. And the poor tailenders, with nothing on them but a modest little “B,” probably meaning “Beaten,” “Beat it,” or “Big loser,” get “23, Skidoo,” for theirs if they even peep or throw a glove in the dirt. And all teams are supposed to be equal.

Another advertisement, this time for shoes in the Trenton Times of 15 May 1906, reads:

No. 23

SKIDOO

Put your trousers over our new model

OXFORD

(Just in)

Known as No. 23 Skidoo

Last—All Leathers

Blucher and Button

Four Dollars.

And this classified ad ran in the Dallas Morning News on 17 June 1906, an attempt to capitalize on the faddish popularity of the phrase:

AGENTS—23 for yours. Show it by wearing a 23 skidoo badge, America’s craze saying, very neat and attractive, made of gold and German silver, can be worn on coat lapels or a scarfpin: send stamp for sample; agents wanted; faster seller out. DEFIANCE CO., 65 West Broadway, New York.

On 30 June 1906, Montana’s Anaconda Standard ran an ad for an everything-must-go sale in a local clothing store that read, “23 ‘Skidoo’ for the Cheap Kinds of Clothes.”

Finally, there is this very meta item from the Harrisburg, Pennsylvania Patriot of 30 June 1906 that comments on the ubiquity of false origins for the phrase:

A former jockey the other day over-estimated his drinking capacity, and when arrested in Cleveland claimed that he had originated the expression “Twenty-three, skidoo for yours.” The magistrate gave him several months in prison, chiefly, let us hope, for claiming the paternity of an expression, that has been given as many different origins and remains as uncertain as the authorship of the letters of Junius, “Beautiful Snow” or The Bread-Winners.

That’s what we know. Both twenty-three and skidoo preceded the combined phrase by some years. Skidoo probably is a variant of skedaddle, and the likely, but by no means certain, explanation for twenty-three is that it comes from a type of con game. The combined twenty-three skidoo first appears in print in 1906 but is likely a few years older in speech.

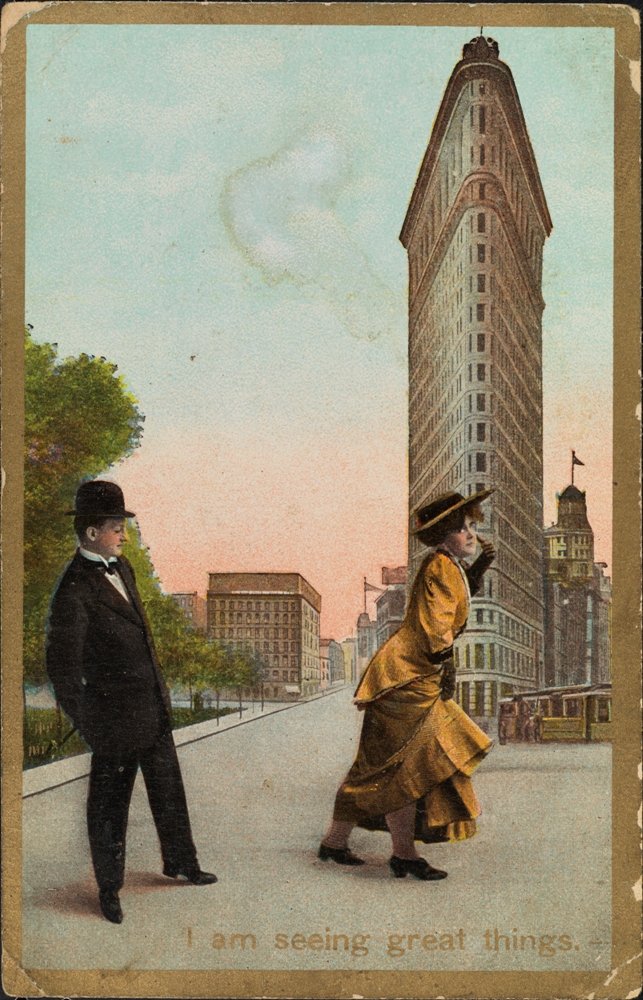

One more popular, but unlikely, explanation for the phrase is that it comes from the wind tunnel effect created by the Flatiron Building in New York City. The building is triangular and sits between Broadway, Fifth Avenue, and Twenty-Third Streets. At twenty-two stories tall, it was one of the first skyscrapers in the city when it was constructed in 1902 and had the effect of channeling winds that were strong enough to lift the skirts of women passing by. Evidently, men would gather on Twenty-Third Street to catch a glimpse of ankle as the skirts were raised. And, legend would have it, that policemen would chase them off with cries of “Twenty-three skidoo!”

The bit about winds raising the skirts of women is true; there are numerous postcards and other ephemera of the era testifying to it. But as we have seen, the slang use of twenty-three predates the building’s construction. If police ever chased men away with twenty-three skidoo, they were using a slang phrase that had nothing to do with Twenty-Third Street. That was merely coincidence and an explanation created after the fact.

Discuss this post