29 July 2022

To gaslight someone is to manipulate them by making them question their own senses or sanity. The verb was coined as a result of George Cukor’s 1944 film Gaslight. Cukor’s film was based on a 1940 British film by Thorold Dickinson, which in turn was based on a 1938 stage play by Patrick Hamilton. But it was Cukor’s film that was a critical and box-office hit, garnering three Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Actress for Ingrid Bergman.

The plot of the film concerns a husband (played by Charles Boyer) who tries to convince his wife (Bergman) that she is going mad in order to cover up a murder he has committed. One of the tricks he uses to convince her that she is hallucinating is to make the gas lamps in their house flicker at random intervals. The verb gaslight, however, does not appear in either film or in the original play. It is simply a plot device and title.

A few years after the film’s debut, however, we get the phrase gaslight treatment. From the Miami Daily News of 16 September 1948:

GASLIGHT—Divorce petitions filed in Dade circuit court in recent weeks reveal an influence traceable to the current run of movies dealing with psychiatric plots, especially those in which the husband tries to convince the wife she is crazy. Several complainants have charged husbands with actions designed to produce fear of mental unbalance, and one suit, filed the other day, claimed the husband “gave her the Gaslight treatment.”

So, by 1948 the concept was in the zeitgeist, even if the verb wasn’t yet.

The Historical Dictionary of American Slang includes an oral attestation of the verb from 1956. We have no particular reason to doubt the date, but the usual caveats apply in regard to memories of usage (reminiscences of exact wording are often inaccurate):

N.Y.C. woman, age 41: To gaslight someone is to play tricks on them to make them think they’re crazy. It comes from the movie Gaslight.

But we do get a print attestation of the verb by 1962. From a television listing for the series Surfside 6 in the Jersey Journal of 12 February 1962:

“Who Is Sylvia?” is a bit more logical and a good deal more interesting than is usual for this series. Sylvia is a beautiful woman whose business-partner husband is “gaslighting” her. (That means he’s trying to drive her crazy.)

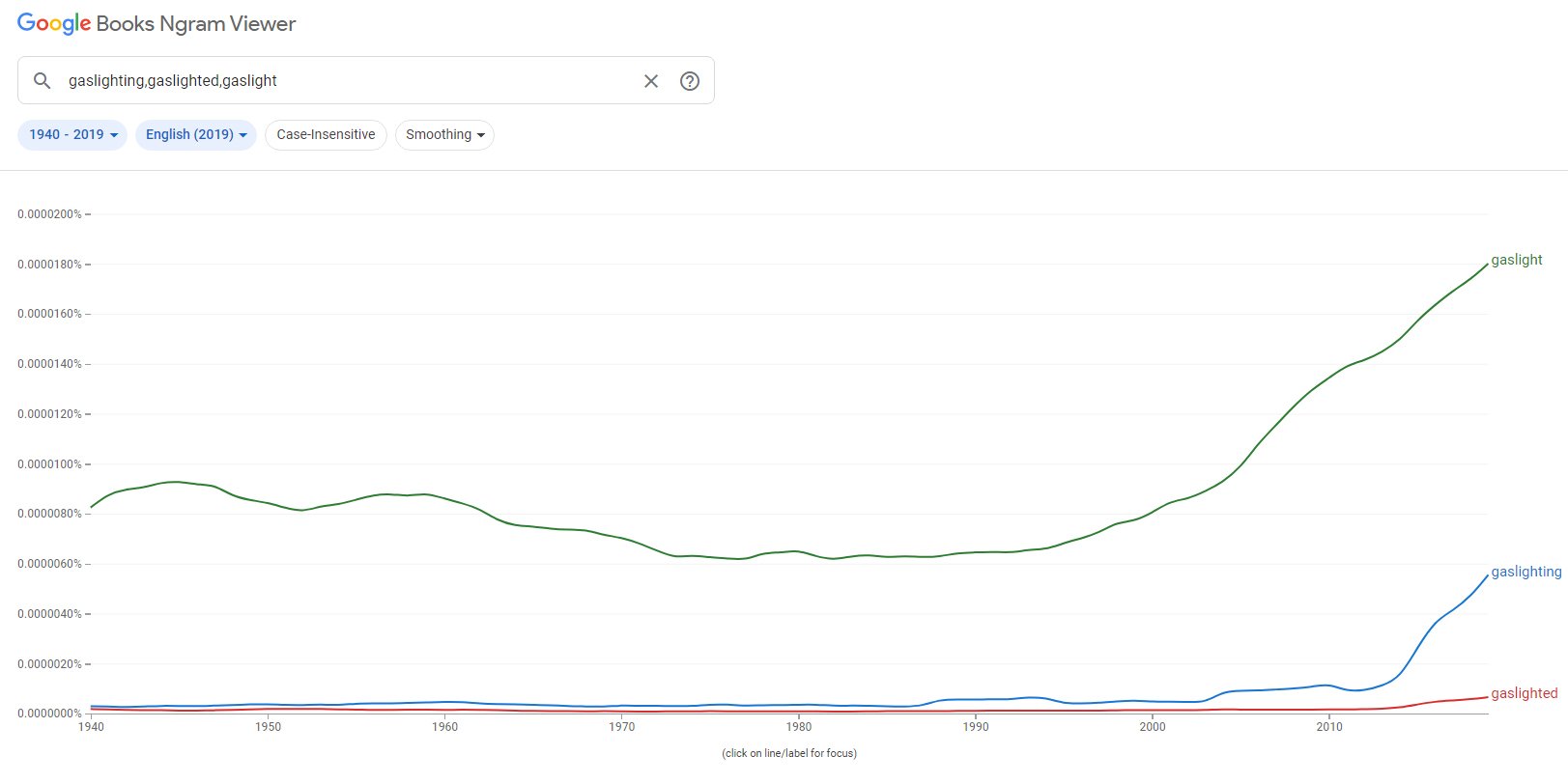

The verb has had a surge in usage in recent years, as shown in the Google Ngram graph. It has also broadened in meaning somewhat, at times referring more generally to deception, as opposed to making someone question their sanity, but still, it often appears in the context of a man deceiving a woman.

Sources:

Google Books Ngram Viewer, accessed 10 July 2022.

“The Journal Pre-Views Tonight’s TV.” Jersey Journal (Jersey City, New Jersey), 12 February 1962, 12. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Lighter, J.E. Historical Dictionary of American Slang, vol. 1 of 2. New York: Random House, 1994, s.v. gaslight, v.

“Miami’s Own Whirligig.” Miami Daily News (Florida), 16 September 1948, 7-B. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, March 2012, s.v. gaslight, v.

Yagoda, Ben. “Gaslighting, Again.” Benyagoda.com, 24 December 2021.

Image credit: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and Loew’s, Inc., 1944. The poster is a public domain image (original copyright not renewed).