17 August 2022

A husband is a male partner in a marriage or long-term relationship, but it can also be a verb meaning to judiciously manage resources, and husbandry is just such judicious management. Today, these two senses seem unrelated, but the history of the word makes the relationship clear.

Our present-day husband comes from the Old English husbonda. That word was modeled on the Old Norse husbondi but formed from common Germanic roots already present in English, hus + bonda. And in Old English the most common meaning of husbonda was that of a householder, a landowner. We see this sense in an Old English translation of the Gospels. It appears in a bit of commentary that follows Matthew 20:28 and the parable of the workers in the vineyard:

Witodlice þon[ne] ge to gereorde gelaþode beoð ne sitte ge on þam fyrmestan setlu[m] þe læs þe arwurðre wer æfter þe cume & se husbonda hate þe arisan & ryman þam oðron & þu beo gescynd

(Certainly, when you are invited to a feast, you do not sit in the first place lest a more honored man arrives later, and the husband says to rise and make room for the other, and you are embarrassed.)

But bonda itself carried the sense of householder and even that of a male partner in marriage in Old English, particularly in legal texts. From the second law code of Cnut in a section regarding the probate of wills:

& þær se bonda sæt uncwydd & unbecrafod, sitte þ[æt] wif & þa cild on þa[m] ylcan unbesacen.

(And where the bonda sat uncontested and not subject to claims, the wife and the child sit similarly uncontested.)

The Quadripartitus, a twelfth-century Latin translation of pre-Conquest English laws, translates this passage as:

Et ubi bonda (id est paterfamilias) mansit […]

(As a rule, the Quadripartitus is an unreliable guide to translation; the translator was not fluent in English, but here the translator appears to have gotten it right.)

In the early Middle English period, a husband could also be someone who manages resources, such as an estate or forest, a specification of the duties of a householder. We see the English word inserted into Anglo-Latin texts starting in the early twelfth century. And the Middle English verb husbonden emerges in the early fifteenth century, meaning to manage resources thriftily. For instance, the verb appears in Thomas Hoccleve’s Balade to the Virgin and Christ:

Wolde god, by my speeche and my sawe,

I mighte him and his modir do plesance,

And, to my meryt, folwe goddes lawe,

And of mercy, housbonde a purueance!(Would God, by my speech and my words,

I might do satisfaction to him and his mother.

And to my merit, follow God’s law,

And of mercy, husband a supply.)

And this verb sense of husband continues on to the present day.

Sources:

2 Cnut § 72. In Felix Liebermann. Die Gesetze der Angelsachsen, vol. 1 of 3. Halle: Max Niemeyer, 1903, 358, 359.

Dictionary of Old English: A to I, 2018, s.v. hus-bonda, n., bonda, n.

Hoccleve, Thomas. “Ceste Balade Ensuyante Feust Translatee au Commandement de Mon Meistre Robert Chichele.” (a.k.a., “Balade to the Virgin and Christ”). Hoccleve’s Works I. The Minor Poems in the Phillipps MS 8151 (Cheltenham) and the Durham MS 3.9. Frederick Furnivall, ed. London: 1892, 67–68. ProQuest.

Middle English Dictionary, 2019, s.v. hous-bond(e, n., hus-bonden, v.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, June 2016, s.v. husband, n.

Skeat, Walter W. The Gospel According to Saint Matthew in Anglo-Saxon, Northumbrian, and Old Mercian Versions, new edition. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1887, 164. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

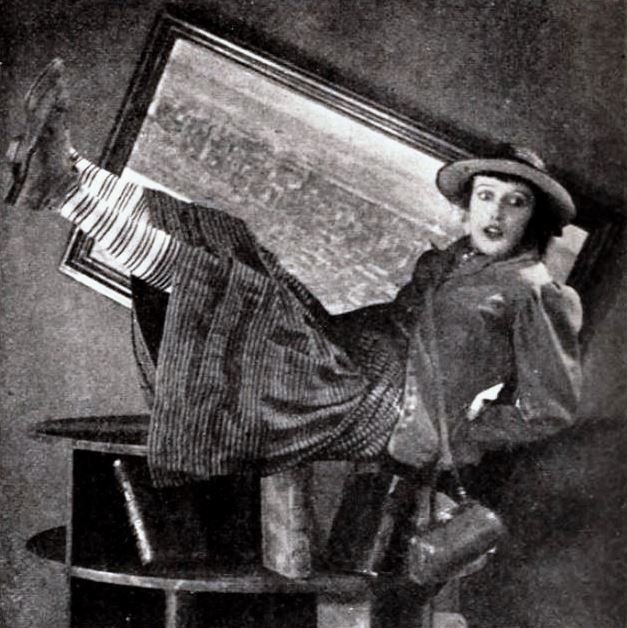

Photo credit: Unknown photographer, 1920. In Tormay, John L. and Rolla C. Lawry. Animal Husbandry. New York: American Book Company, 1920, 148. Public domain image.