31 October 2022

[2 November 2022: added fact about the Old English plural of boc.]

In Present-Day English, book generally refers to a codex, but originally it could refer to any document or text. The etymology of book is a bit uncertain. It has cognates in other Germanic languages, but the exact root is up for debate.

The traditional etymology has the Old English boc, or book, being related to the word for beech, which could also be spelled boc, the idea being that beech wood was used for writing tablets or that runes would be carved into beech wood or beech bark. This hypothesis has been called into question because the two words are in different noun classes in West Germanic and the book sense is recorded before the beech sense. But these are hardly ironclad arguments. In North Germanic languages, the words occupy the same noun class—Old English was heavily influenced by Old Norse and such classifications are modern structures that are useful as a descriptive tool to linguists today and may not reflect etymology—and gaps in the Old English corpus are so large that any pretense of accurate dating is questionable.

The alternative explanation is that book comes from the Proto-Indo-European root *bhag-, meaning portion or lot, the idea being that runes would be written on pieces of wood used for the casting of lots or that a letter or rune was only a portion of the language. Militating against this is that the Proto-Indo-European root *bhago- gives us the word for beech, further evidence that one must take PIE roots with a grain of salt; they’re what present-day scholars think the language may have looked like, an approximation of the dialects that were spoken some three thousand years ago. And, while the PIE theory is undoubtedly correct in general, the detailed descriptions constructed by present-day scholars may very well be wrong. Perhaps beech wood was used for the casting of lots; who knows?

Here is an example of the use of the Old English boc, meaning book, from Ælfric of Eynsham’s preface to his translation of Genesis. (It’s really a letter to the nobleman who commissioned the work, but the text is generally labeled as a “preface” nowadays.) In the work, Ælfric expresses concern that some readers or audiences might interpret the Bible literally when it is clearly using metaphor:

Hu clypode Abeles blod to Gode buton swa swa ælces mannes misdæda wregað hine to Gode butan wordum? Be ðisum lytlan man mæg understandan, hu deop seo boc is on gaslicum andgyte, ðeah ðe heo mid leohtum wordum awriten sy.

(How did Abel’s blood call out to God, except just as each person’s misdeeds accuse them before God without words? By these little things, one may understand how deep the book is in spiritual meaning, although it is written with plain words.)

A fun little fact is that the Old English plural of boc was bec. This plural persisted through the early Middle English period when it was replaced by the regular / s / plural inflection. Had it not changed, the modern plural of book would be beech.

There was also a verb form of the word, bocian, meaning to grant via charter a piece of land, that is to set the grant down in writing.

The sense of boc meaning beech tree or beech wood is rarer, with only eight appearances in the surviving Old English corpus. All of these are in glosses of Latin texts with the exception of the Old English translation of the Rule of Chrodegang. Chrodegang was an eighth-century Frankish bishop who developed a monastic rule based on that of Benedict. In the Rule, there are regulations regarding how much meat monks could consume, and in one passage Chrodegang addresses the problem of a famine or bad harvest limiting the non-meat protein supply:

Gif hit þonne gebyrað on geare þæt naðer ne byð on þam earde ne æceren ne boc ne oðer mæsten þæt man mæge heora flæscþenunge forð bringan, wite se bisceop oððe se ðe under him ealdor is, þæt hi hit þurh Godes fultum asmeagan þæt hi frofer hæbben & nanne wanan.

(If it happens in a year there are in the land neither acorns nor beech nor other nuts that one may produce for their allowance of meat, the overseeing bishop or he who is senior under him, may resolve it through God’s assistance so that they have solace and do not want.)

(In the above translation, I am using meat to translate flaesc (flesh). The Old English mete, which gives us the present-day meat, referred to food generally, not just the flesh of animals.)

As stated, this sense of boc was rare in Old English and by the Middle English period could only be found in compounds, such as boctreow (beech-tree) and bokeholte (beech woods).

Confusing things further, Old English also had the form bece, which would develop into our modern form beech during the Middle English period. As discussed above, this form may or may not come from the same root as the book sense. We perhaps see this word in opening of the thirteenth-century poem The Owl and Nightingale. The poem survives in two manuscripts, with Oxford, Jesus College MS 29 reading:

Þe nihtegale bigon þo speke

In one hurne of one beche,

& sat vp one vayre bowe,

Þat were abute blostme ynowe,

In ore vaste þikke hegge

I[m]eynd myd spire & grene segge.(The nightingale began to speak from a niche of a beech and sat upon a fair bough that was covered in blossoms, it was in one vast, thick hedge, mingled with stalks and green sedge.)

The other manuscript, London, British Library, MS Cotton Caligula A.ix reads hurne of one breche (corner of a field). A third possibility is that it is a survival of the Old English bæc or bece, meaning valley. All three words make sense in the context. But in any case, the Present-Day beech descends from the Old English bece.

Shifting gears to the twentieth century, the idiom to throw the book at, meaning to deliver the harshest possible punishment for an offense, does not make literal sense. The idiom is an Americanism that dates to at least 1911, when it appears in George Howard Bronson’s novel An Enemy to Society. Unlike many similar idioms, however, we know what the underlying metaphor is. The passage in this novel explains the metaphor, making sense of the idiom:

If I'd a joined one of these here political clubs or secret organizations and always voted “right” and bin a good “party” man, I'd never done no three years upriver fer burglary. But as soon as they finds you've got no political pull, the judges and all git very moral; throw the book at you and tell you to add up the sentences in it.

At least one origin in all this is clear.

Sources:

Ælfric. “Preface to Genesis.” The Old English Version of the Heptateuch. S.J. Crawford, ed. Early English Text Society O.S. 160. London: Oxford UP, 1922, lines 70–74, 78–79. London, British Library, MS Cotton Claudius B.iv.

American Heritage Dictionary of Indo-European Roots Appendix, s.v. bhag-, bhago-.

Atkins, J.W.H., ed. The Owl and the Nightingale. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1922, lines 13–18, 2–5. London, British Library, MS Cotton Caligula A.ix, fol. 233r. Oxford, Jesus College, MS 29, fol. 229r. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Cartlidge, Neil. The Owl and the Nightingale. Exeter: U of Exeter Press, 2001, 107.

Dictionary of Old English: A to I, 2018, s.v. boc1, n., boc2, n., bocian, v., bece, n., bæc2, n.

Howard, George Bronson. An Enemy to Society. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Page, 1911, 42. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Merriam-Webster New Book of Word Histories. Springfield, Massachusetts: Merriam-Webster, 1991, s.v. book.

Middle English Dictionary, 2019, s.v. bok-, n.2., beche, n., brech(e, n.

Napier, Arthur S., ed. The Old English Version of the Enlarged Rule of Chrodegang Together with the Latin Original. Early English Text Society O.S. 150. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, 1916, 6.9–13, 15. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, March 2014, s.v. book, n., book, v.; second edition, 1989, s.v. beech, n.

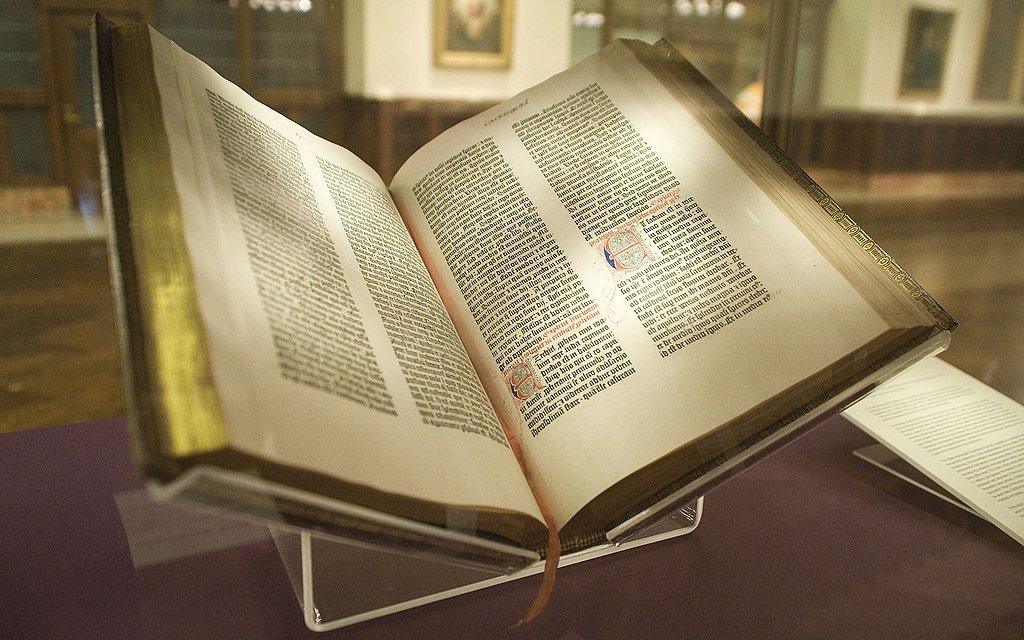

Photo credit: Kevin Eng, 2009. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.