14 December 2022

A paparazzo is a freelance photographer who snaps shots of celebrities for sale to media outlets. Paparazzi are known for being aggressive and transgressive in getting their money shot. The name comes from just such a character in Federico Fellini’s 1960 film La Dolce Vita named Paparazzo, played by Walter Santesso.

Paparazzo is an Italian surname, so naming a character that would not be unusual. Fellini claimed that he took the name from an opera libretto and that to him the name suggested a biting insect, a pest. But his co-writer Ennio Flaiano claimed to have contributed the name, and that his inspiration came from its use in George Gissing’s 1901 novel By the Ionian Sea, where it was the name of a hotelier. Gissing’s novel was translated into Italian in 1957, and presumably Flaiano had recently read it. It has also been suggested that paparazzo means clam in the Abruzzi dialect, from which Flaiano hails, and is a metaphor for the opening and closing of a camera shutter.

In Italian, paparazzo is the singular form of the word and paparazzi the plural, but that distinction has not been consistently observed in English, which commonly uses paparazzi for both singular and plural. The earliest use of the word to refer to a freelance photographer (other than the character in the film) that I’m aware of is in Time magazine from 14 April 1961. Time does make the distinction between singular and plural forms:

Trouble that can be shot with a camera is Kroscenko’s business. A three-block stretch of the Via Veneto, cascading from the Aurelian Wall to the U.S. embassy is his favorite hunting ground. Here, in the glittering array of hotels, smart shops and open-air cafés, throng Kroscenko’s picturesque prey. He is a paparazzo,* one of a ravenous wolf pack of freelance photographers who stalk big names for a living and fire with flash guns at point-blank range.

Shot from a Box. The paparazzi are a small crew—a couple of dozen at most—and they are more bullyboys than news photographers. They lounge beneath lampposts, lips leaking cigarettes, cameras drawn like automatics. “Come esce lo faccio secco [When he comes out, I’ll drill him],” they snarl, while waiting for their quarry to open a nightclub door. Then the paparazzi attack.

The footnote reads:

* A name coined by Movie Director Federico Fellini for a freelance photographer in La Dolce Vita, his gamy study of Roman café society. “Paparazzo,” says Fellini, “suggests to me a buzzing insect, hovering, darting, stinging.”

But just a year later, a United Press International article from 13 May 1962 uses paparazzi as both singular and plural. The singular use appears in a quote by the aforementioned Ivan Kroscenco (different spelling in the UPI piece). The quote is at a crossroads between multiple languages. Kroscenco was Russian born and living in Italy, but the quote is rendered in English. This is exactly the type of situation where one would expect strict distinctions between singular and plural forms to be blurred:

Russian-born Ivan Kroscenco is the unofficial “king of the paparazzi.”

A squat man of 32—and always dressed in a black leather jacket—Kroscenco explained that “anybody can take regular photographs. But we want the ones that nobody else can take.

“You’ve got to be fast with a camera, get the instant. Zot, like that,” he said, indicating a fast shot from the hip.

* * *

“Now, everybody claims to be a paparazzi. But I started it and there are only half a dozen of us. The best are just hangers on. But they don’t get much anyway. They don’t know how to operate.”

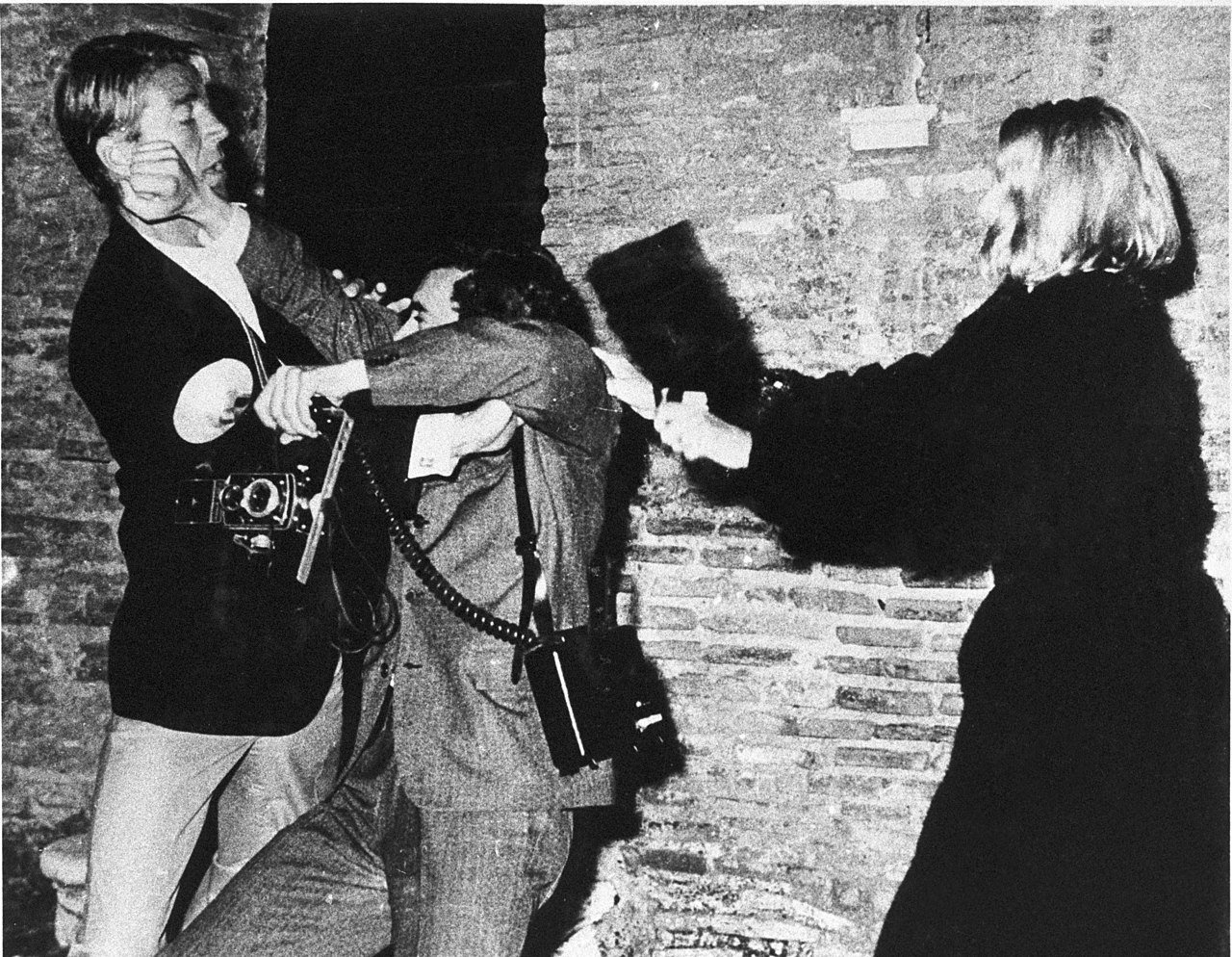

But a few months later we see the singular paparazzi in an all-English context when the Philadelphia Daily News of 20 September 1962 ran a headline that read, “Ingrid Pops A Paparazzi.” The article is about actor Ingrid Bergman slapping a photographer who was pestering her while she was shopping with her daughters.

Bergman would not be the last celebrity to slug a paparazzi. There is this that appeared in Washington, D.C.’s Evening Star on 7 September 1964:

Peter O’Toole’s telling punch at a paparazzi in Rome has all the Hollywood stars cheering. The pesky flies (literal translation) make life miserable for any foreign celebrity on the Via Veneto. It takes an Italian to take it all in stride—as Rosanno Brazzi did when we were driving with some of his guests out of the Excelsior driveway and the photographers descended like locusts. Rosanno grabbed the wife of a friend and went into a big kissing pose. And how those cameras clicked! When wife Lydia saw the photographs in a magazine, she laughed and laughed. She knows the paparazzi. And her spouse.

Can one blame a celebrity for punching a paparazzi who disrupts their sweet life?

Sources:

Graham, Sheilah. “Short Honeymoon for Anna Marie.” Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), 7 September 1964, A-19. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

“Ingrid Pops a Paparazzi.” Philadelphia Daily News, 20 September 1962, 3. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, March 2005, s.v. paparazzo, n. (and adj.), paparazzi, n.

“Paparazzi on the Prowl.” Time, 14 April 1961, 81. Time Magazine Archive.

“Tale of Two (Eternal) Cities: Just Eternal and Eternally Political” (United Press International). Springfield Union (Massachusetts), 13 May 1962, 16A. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Image credit: Unknown photographer, 1963. Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.