11 January 2023

Trivia and trivial stem from the medieval Latin trivium. In classical Latin, a trivium was a place where three roads met. But in the Middle Ages, the word was applied to the curricula of schools and universities which consisted of the seven liberal arts, divided into two stages. The elementary stage, or trivium, consisted of grammar, rhetoric, and logic, and the advanced stage, or quadrivium, consisted of arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music. Trivial, therefore, meant something basic, learned early in one’s schooling. The noun trivia, meaning bits of inconsequential knowledge, is quite recent, however, dating only to the twentieth century and the game of trivia to the 1960s.

Trivium, in the medieval curricular sense, appears in English by the mid fifteenth century. John Lydgate refers to it in his version of the Secreta Secretorum (Secret of Secrets), a pseudo-Aristotelian encyclopedic text that was probably composed in Arabic in the tenth century. By the mid twelfth century it had been translated into Latin. The relevant passage from Lydgate’s poetic translation into English reads:

Yif I shulde talke / in scyencys tryval,

Gynnyng at grameer / in signes and figurys,

Or of metrys / the feet to make equal,

be tyme and proporcioun / kepyng my mesurys,

This lady lyst nat / to parte the tresourys

Of hire Substaunce / to my Childhood incondigne,

Which am no aqueynted / with the mysys nyne.

(If I should speak in the sciences trivial, beginning with grammar in signs and figures, or of meters, making the feet equal in time and proportion, keeping my measures. This lady does not desire to give the treasures of her substance to my unworthy childhood, in which I am not acquainted with the nine muses.)

The adjective trivial meaning something in three parts appears at about the same time. From a mid-fifteenth century anonymous translation of Ranulf Higden’s Polychronicon, part of a listing on Higden’s source material:

Giraldus of Wales, which describede Topographie of Irlonde, Itinerary of Wales, and the Lyfe of Kinge Henry the Secunde, under a triuialle distinccion

(Gerald of Wales, who wrote the Topography of Ireland, the Itinerary Through Wales, and the Life of King Henry II, in trivial [i.e., three] parts.)

Higden’s original Latin reads triplici distinctione. John Trevisa had penned an earlier English translation of Higden’s work, but he did not translate this section; he simply copied the Latin list of sources.

It wouldn’t be until the Early Modern period that the adjective trivial would come to mean ordinary, everyday, inconsequential, or trifling things. From an essay by Thomas Nashe that was published in 1589, in which he uses the adjective to refer to the translators he usually consults:

I'le turne backe to my first text, of studies of delight; and talke a little in friendship with a few of our triuiall translators.

And Shakespeare used it in the inconsequential sense in Henry VI, Part 2. In Act 3, Scene 1, various nobles are debating whether the Duke of Gloucester should die even though the king still trusts him; the Duke of Suffolk advocates killing him:

But in my minde, that were no pollicie:

The King will labour still to saue his Life;

The Commons haply rise, to saue his Life;

And yet we haue but triuiall argument,

More then mistrust, that shewes him worthy death.

The sense of trivia meaning bits of inconsequential knowledge had yet to appear, but a step in that direction was taken by a 1716 work by John Gay, Trivia: or, the Art of Walking the Streets of London. In Gay’s work, Trivia is the name of the muse who inspires him to write. The opening of Gay’s work reads:

Through Winter Streets to steer your Course aright,

How to walk clean by Day, and safe by Night,

How jostling Crouds, with Prudence, to decline,

When to assert the Wall, and when resign,

I sing: Thou Trivia, Goddess, aid my Song,

Thro’ spacious Streets conduct thy Bard along.

Trivia is also the Roman name of Hecate, goddess of magic, night, crossroads, and travelers, so she is an appropriate muse for Gay’s work. And he is also alluding to Book 4 of Virgil’s Aeneid which contains the lines:

Nocturnisque Hecate triviis ululata per urbes

et Dirae ultrices et di morientis Elissae,

accipiter haec

(Hecate, whose name is howled by night in city streets, and avenging Furies and gods of dying Elissa: hear me now.)

But that is not the only reference to Virgil and to trivium in Gay’s work. The work also bears an epigraph from Virgil’s Eclogue number 3, a dialogue between Menalcas and Damoetas:

Non tu, in Triviis, Indocte, solebas St[r]identi, miserum, stipula, disperdere Carmen?

(Wasn’t it you at the crossroads, unskilled, who used to destroy a wretched tune with your shrieking pipe?)

But with a change in punctuation (the punctuation is a later intervention by editors and not original to Virgil), tu, in Triviis indocte could be read by an eighteenth-century reader like Gay as you, uneducated in the Trivium. By using this epigraph, Gay is denigrating his critics before they can respond to his work, simultaneously accusing them of ignorance and of being poor poets and musicians.

Gay is also playing off Alexander Pope’s Rape of the Lock, which had been published a few years before in 1712, and which would have been very familiar to his readers, whose opening lines read:

What dire offence from am’rous causes springs,

What mighty contests rise from trivial things,

I sing—This verse to Caryl, Muse! Is due.

Gay’s work did not use trivia in the sense of inconsequential knowledge, but it inspired writer and scholar of eighteenth-century literature Logan Pearsall Smith to use Trivia as the title of a 1902 collection of essays, which he credited to a fictional Anthony Woodhouse. His own mother said of the collection that it “began nowhere, ended nowhere and led to nothing.” The book was initially a failure, printed in few numbers privately, but it has been more successful in later reprints.

Other uses of the noun trivia would follow, like this passage from the Glasgow Herald of 21 July 1920:

Mr. Arnold Bennett, in his recent account of a yachting cruise, seems to have deliberately avoided the “show places,” and has made a fascinating narrative out of the apparently trivial things; crowds in marketplaces, the window contents of little shops, the manner of ordinary people pursuing their ordinary avocations. Mr. Bennett is of course one of the rare observers with the equally rare gift of imparting colour to the commonplace. But his method suggests the amount of human interest and knowledge that may lurk in the trivia of holiday experience.

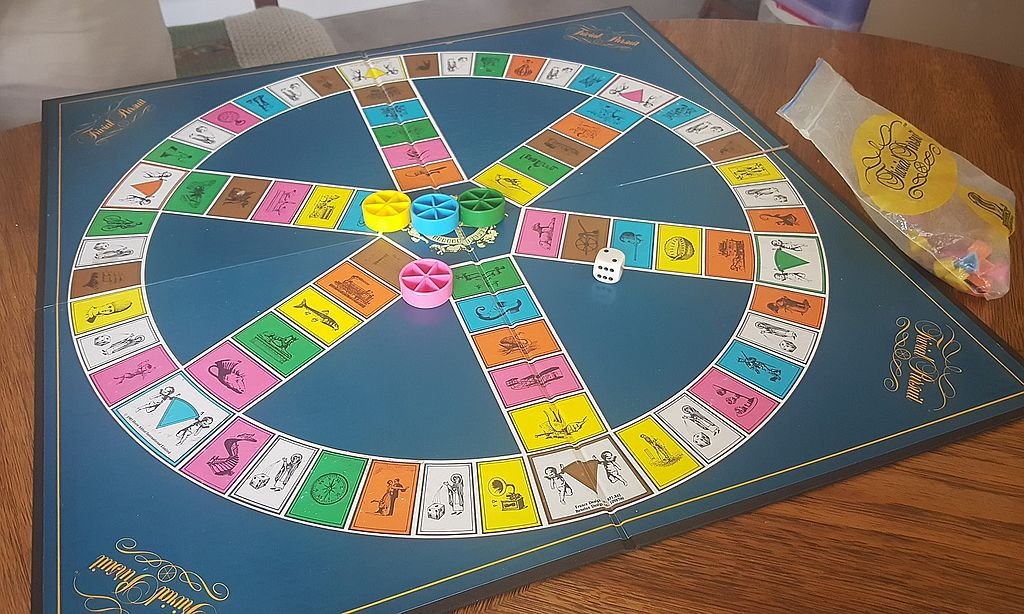

The game of trivia, played in various forms but which all feature questions about inconsequential knowledge appears in the 1960s. It got its start among college students in the United States, and can now be found on television game shows, in pubs and bars, and in board game form. Here is an early reference in Columbia University’s Columbia Spectator of 5 February 1965:

Has anyone ever asked you what was the name of the Lone Ranger’s nephew? Has anyone ever challenged you to name the snake that appeared in “We’re No Angels?” Maybe someone has dared you to name Superman’s Kryptonic parents? If any of these things have happened to you then, no doubt, you have been involved in a game of “trivia.”

Trivia is a game which is played by countless young adults who on the one hand realize that they have misspent their youth and yet, on the other hand, do not want to let go of it. It is a combination of “Information Please” and psychoanalysis, in which participants try to stump their opponents with the most minute details of shared childhood experiences.

And in a way, the entire Wordorigins.org website consists of trivia.

Discuss this post