13 March 2023

[Added reference to nibble on 15 March 2023.]

This website comes to you in bits and bytes. But what are bits and bytes and why are they called that?

A bit is a basic unit of information that represents one of two alternative states, typically written as a 1 or a 0. The term was coined by mathematician John Wilder Tukey c.1947 while he was working at Bell Labs and Princeton University in New Jersey. The term is a play on words. It is supposedly an abbreviated form of Binary digIT, but it is also so called because it is a small piece, or literally bit, of information. It may, in fact, be a backronym, that is an acronym created from an already existing word. Tukey and his colleagues may have started talking about bits of information, and later Tukey invented the acronym from the word.

The first known use of bit in print is in a 1948 article by Tukey’s colleague at Bell Labs, Claude Shannon. The article, A Mathematical Theory of Communication, is a foundational text in the science of information theory, and its role in the history of the word bit is simply a footnote to the article’s scientific importance:

The choice of a logarithmic base corresponds to the choice of a unit for measuring information. If the base 2 is used the resulting units may be called binary digits, or more briefly bits, a word suggested by J.W. Tukey.

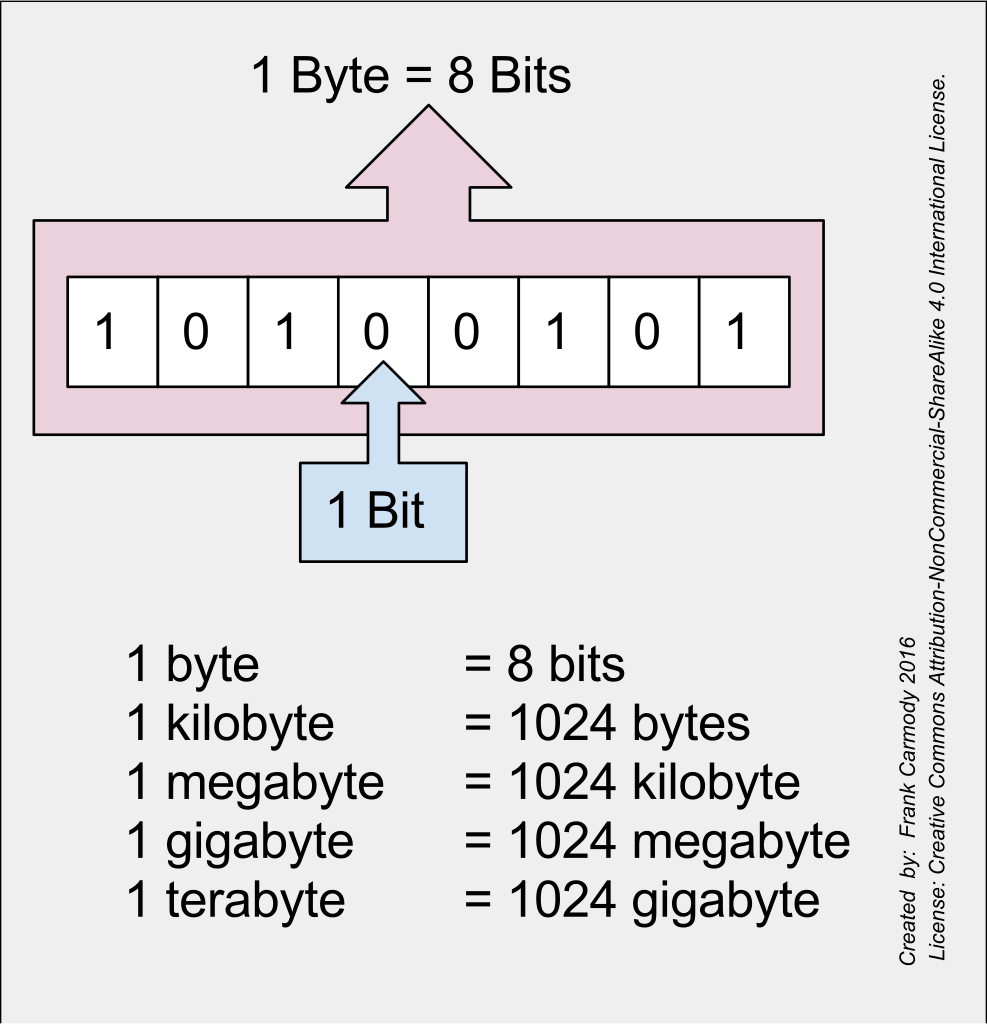

Byte appears around a decade later, and it too is a play on words, this time playing off of bit and bite/bite-size. A byte is a grouping of bits, typically but not necessarily eight bits, that is operated upon as a single unit. The letters of the Latin alphabet and Arabic numerals can each be represented by a single byte. (Writing systems with more than 256 characters, such as Chinese, require two or more bytes to represent each character.)

The earliest use of byte in print that I have found is in a June 1959 paper presented at a conference and published in the IRE Transactions on Electronic Computers, although the wording here indicates the term was already in use:

For operations upon fields of variable length, it is generally necessary to specify the inner structure of the field. For alphabetic fields this consists of the individual letters or other characters. For numeric fields, the structure includes the sign, if any, and the digits, if separately encoded. These sub-units collectively have been named bytes. Since the coded representation of a byte naturally varies in size, byte sizes of one to eight bits may be specified and used.

In 1962, one of the authors of that paper, Werner Buchholz, edited a book on computer systems that expanded a bit on byte’s origin:

Byte denotes a group of bits used to encode a character, or the number of bits transmitted in parallel to and from input-output units. A term other than character is used here because a given character may be represented in different applications by more than one code, and different codes may use different numbers of bits (i.e., different byte sizes). In input-output transmission the grouping of bits may be completely arbitrary and have no relation to actual characters. (The term is coined from bite, but respelled to avoid accidental mutation to bit.)

Nowadays, bytes are usually expressed in larger units designated with a prefix taken from Greek, such as kilobyte or terabyte:

kilo- from χίλιοι (thousand); 1,024 bytes

mega- from μεγα (great); 1,024 kilobytes

giga- from γίγας (giant); 1,024 megabytes

tera- from τέρας (monster); 1,024 terabytes

peta- from penta- πέντε- (five) and tera-; 1,024 terabytes

exa- from hexa- ἕξ (six); 1,024 petabytes

There is also the semi-humorous nibble or nybble referring to half a byte. That usage dates to at least 1967.

Sources:

Brooks, Jr., F.P., G.A. Blaauw, and W. Buchholz. “Processing Data in Bits and Pieces.” IRE Transactions on Electronic Computers, EC-8.2, June 1959, 121. IEEEXplore.org.

Buchholz, Werner, ed. Planning a Computer System: Project Stretch. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1962, 40. Archive.org.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. bit, n.4, byte, n.; draft additions, 1993, s,v. bite, n.; third edition, September 2003, s.v. nibble, n.

Shannon, C.E. “A Mathematical Theory of Communication.” Bell System Technical Journal, 27.3, July 1948, 380. IEEEXplore.org.

Image credit: Frank Carmody, 2016. Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.