17 April 2023

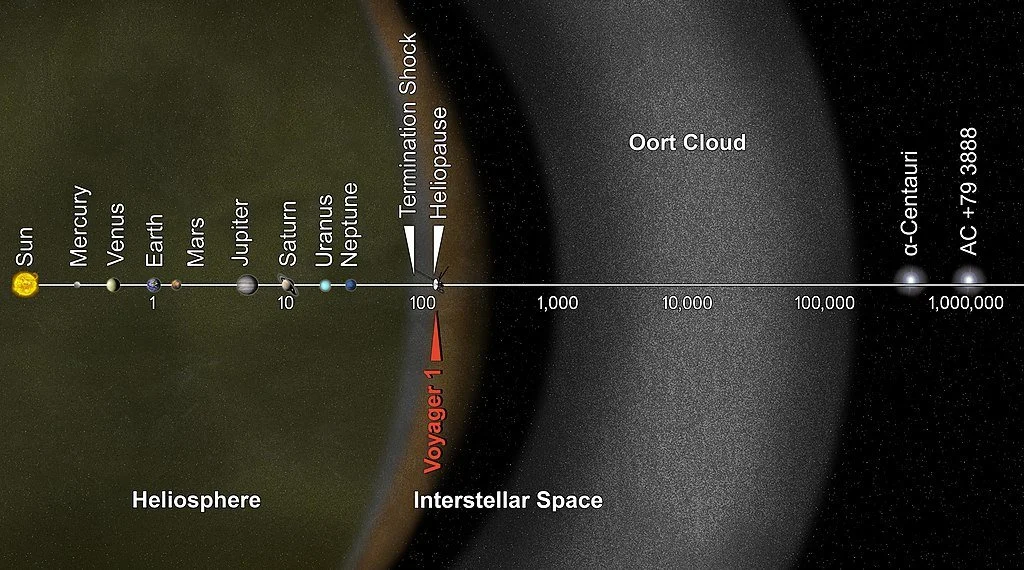

The Oort cloud is a mulititude of icy celestial bodies that is postulated to exist beyond the Kuiper belt and that is the source of long-period comets (i.e., those that have orbital periods greater than two-hundred years). The cloud is named after astrophysicist Jan Oort (1900–1992) who postulated its existence in 1950. But Oort was not the first to do so. He was preceded by Ernst Öpik (1893–1985), who had postulated its existence in 1932. As a result, the cloud is sometimes referred to as the Öpik-Oort Cloud. In his description, Öpik used the word cloud:

If, however, among our observable objects there is a sensible proportion of meteors with R exceeding 10000 a.u., it may be only the result of a very peculiar distribution of meteoric matter at the outskirts of the solar system—a kind of a meteoric cloud, or shell, of a density much higher than may be anticipated from the observed frequency of solar meteors caught on the surface of the terrestrial atmosphere.

(In this paper, Öpik used meteors as a general category that included comets “for the sake of simplicity.”)

While Oort also used the word cloud in his 1950 paper, like Öpik he did not append his own name to it:

From a score of well-observed original orbits it is shown that the “new” long-period comets generally come from regions between about 50 000 and 150 000 A.U. distance. The sun must be surrounded by a general cloud of comets with a radius of this order, containing about 1011 comets of observable size; the total mass of the cloud is estimated to be of the order of 1/10 to 1/100 of that of the earth. Through the action of the stars fresh comets are continually being carried from this cloud into the vicinity of the sun.

The term Oort cloud is in place by 1961, when it appears in an article in the Bulletin of the Astronomical Institute of Czechoslovakia. Given the casual use of the term without explanation in an article that is only tangentially related to the cloud, it would appear that Oort cloud was already in common use among astronomers by this date:

Comets with [cube root of] p < 0.1, not included in Fig. 5, are members of the Oort cloud.

In early use, one also finds the form Oort’s comet cloud or the Oort cometary cloud, as in this article, a 1964 translation of a 1963 Soviet journal article:

On the basis of the analogy between the Lorentz force and the Coriolis force in an inertial system, the equations of hydrodynamics are formulated here for an ensemble of noncolliding particles in such a system. The equations derived are similar to the equations of collisionless magnetohydrodynamics. The evolution of rotating objects (the Galaxy, galactic clusters, meteor streams, the Oort cometary cloud, etc.) can be discussed on the basis of these equations.

The term starts appearing in the popular press in 1973 in articles discussing the comet Kohoutek of that year. This one is from the Christian Science Monitor of 20 November 1973:

Experts speculate that comets originate somewhere beyond the orbit of Pluto in Oort’s cloud, named after Jan Oort. The Dutch astrophysicist theorized that there exists a ring of comet-like snowballs in the outer reaches of the solar system. On rare occasions one is nudged out of place and begins falling toward the sun.

The Oort cloud has never been directly observed. Its existence is merely theorized based on the behavior of long-period comets.

Sources:

Grass, Stephen. “…Astronomers Await This Burning Sphere from Beyond Pluto.” Christian Science Monitor, 20 November 1973, B8. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Marochnik, L.S. “Collisionless Hydrodynamics in Inertial Frames of Reference” (translation). In Soviet Astronomy, 8.2, September–October 1964, 202–09 at 202. Original in Astronomicheskii Zhurnal, 41.2, 22 November 1963, 264–73. NASA Astrophysics Data System.

Oort, J.H. “The Structure of the Cloud of Comets Surrounding the Solar System, and a Hypothesis Concerning Its Origin.” Bulletin of the Astronomical Institute of the Netherlands, 11.408, 13 January 1950, 91–110. NASA Astrophysics Data System.

Öpik, E. “Note on Stellar Perturbations of Nearly Parabolic Orbits.” Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 67.6, October 1932, 169–83 at 181. JSTOR

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, June 2004, s.v. Oort, n.

Sekanina, Z. “Collisions of Comets with Dust Particles in Interplanetary Space” (30 August 1961). Bulletin of the Astronomical Institute of Czechoslovakia, 13, 1962, 155–163 at 162. NASA Astrophysics Data System.

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech, 2013. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain image.