3 May 2023

To drink the Kool-Aid is a slang Americanism meaning to exhibit unswerving loyalty and belief in one’s leaders or convictions. It was originally a reference to a massacre/mass suicide by members of the People’s Temple in Jonestown, Guyana on 18 November 1978. Over 900 people died on the orders of the cult’s leader, Jim Jones. Many of those who died apparently willingly drank a cyanide-laced drink, but others were forcibly made to do so or were injected with cyanide. But as the memory of that horrific event has faded, the phrase has largely lost its macabre association

Kool-Aid is a brand of flavored drink mix. The name is a respelling for trademark purposes of cool + -ade. It was trademarked in 1927. Ironically, Kool-Aid was not actually used at Jonestown, but rather another brand, Flavor Aid, was. But Kool-Aid had a much larger market share and was better known by far, and so it became associated with Jonestown in the public consciousness.

We see the metaphor start to take hold a few months after the deaths at Jonestown. The following is from a 14 January 1979 op-ed in the Washington Post. It uses the metaphor, but not the phrasing, opting instead for pass around the Kool-Aid:

This is not an age of reason. The Jonestown massacre was an event perfectly typical of the epoch: You can fool most of the people with absolutely any nonsense, all the time, and a belief that the mercenaries were coming for them out of the jungle, that the only escape was mass suicide, was completely normal.

The climax of Leni Riefenstahl’s film of the Nuremberg rally comes with Hess shouting to the frenzied faithful, “Hitler is the Party, the Party is Hitler,” just before the Leader appeared. No doubt about it, if he had ordered the SS to pass around the Kool-Aid, all those crewcut Nazis would have tossed it back with the same fervor with which they cheered Hess’ ravings.

To a large extent, in fact, the latter part of the Second World War was a case of mass suicide: Everybody in Germany knew that the war was lost, and that going on fighting was merely a good way of getting killed. They followed their Leader, all the same, their eyes open, right to the end.

The exact phrasing drink the Kool-Aid appears a few months later. Here it is in a 21 July 1979 article in the Charlotte Observer about a cabinet shake-up in the Carter administration:

“What is going on around here?” trumpeted the Washington Post in an editorial one morning. Cartoonists dipped their pens in acid. Gallows humor abounded.

“Don’t drink the Kool-Aid,” a reference to the mass deaths at Jonestown in Guyana, was the gag of the day in the White House press room Tuesday when the mass resignation offers were announced.

Everywhere in the capital, people seemed to talk of little else but Carter’s reshuffling of the federal house of cards.

The earliest citation of the metaphorical use in the Oxford English Dictionary quotes poet Allen Ginsberg at a poetry reading during a protest against nuclear power on 20 February 1981:

He read to his audience from his earlier poetry like the famed “Howl” but also offered “Plutonium Ode,” a more recent protest against nuclear power and Three Mile Island[.]

“We are all being put in the place of the citizens of Jonestown, being told by our leaders to drink the Kool-Aid of nuclear power,” he said stressing his dismay at the return of right-wing politics and morality in America[.]

But by 1981, the phrase had started to become disassociated with the horrors of Jonestown. An 18 October 1981 article in the Kansas City Star about the air traffic controllers’ strike blithely uses the phrase in a non-life-threatening context and without direct reference to Jonestown:

The one enduring mystery in the controllers’ strike is why, if their demands are laughable, have so many controllers stuck with them so long? What made them “drink the Kool-Aid,” as one non-striking controller in Memphis put it?

That’s the way with such phrases. Over time, as the events that inspired the original metaphors fade, the phrases lose some of their power.

Sources:

Alter, Jonathan. “Air Controllers Were Overstaffed.” Kansas City Star (Missouri), 18 October 1981, 4B/1. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers,

Boyd, Robert S. “Washington Wobbles After Whirlwind Week.” Charlotte Observer (North Carolina), 21 July 1979, 1/2. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Brogan, Patrick. “The Age of Un-Reason.” Washington Post, 14 January 1979, G8/1. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Graham, Eileen. “Ginsberg Tells of Kool Aid of Nuclear Power.” Gettysburg Times (Pennsylvania), 20 February 1981, 1/5. NewspaperArchive.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, December 2005, s.v. Kool-Aid, n.

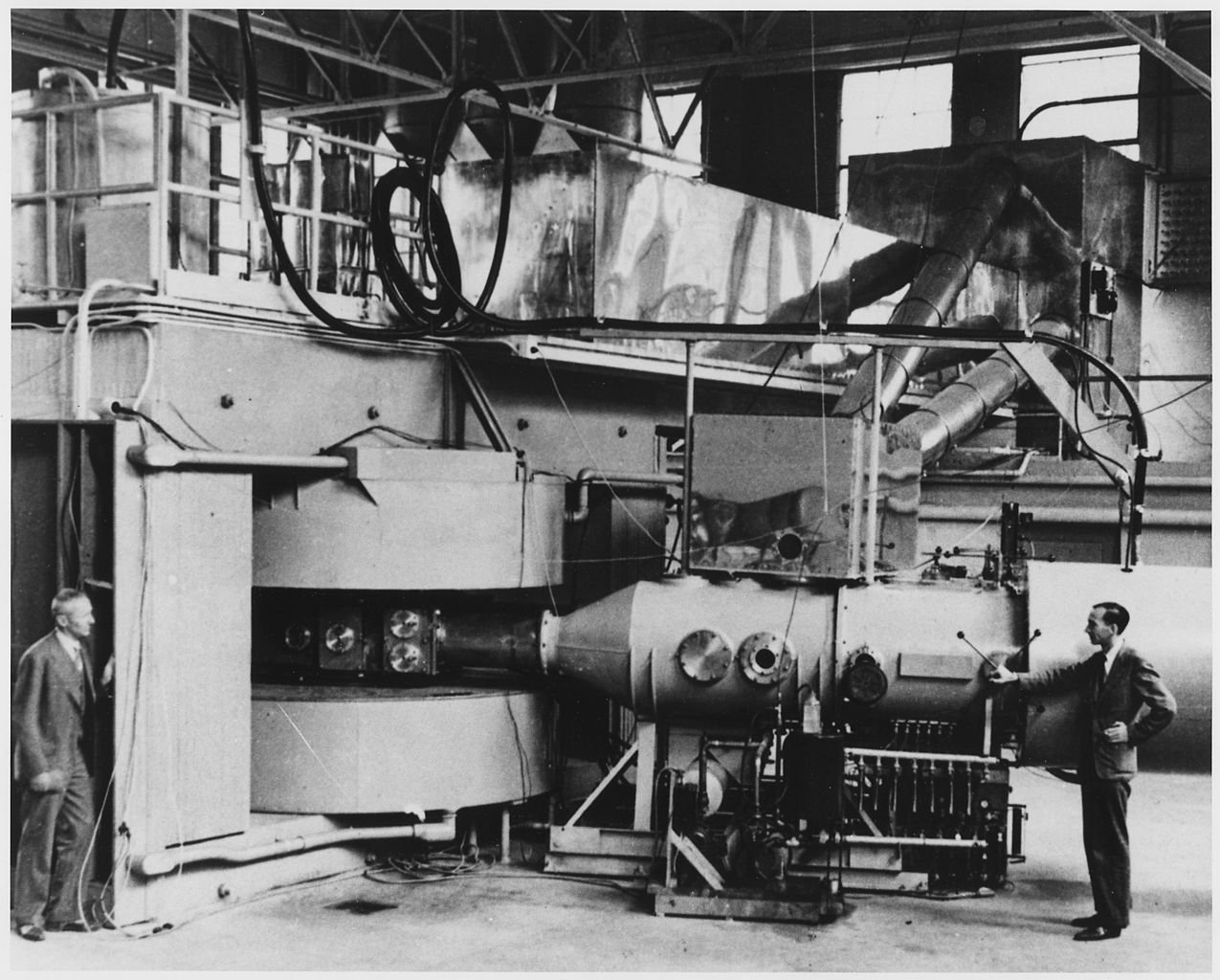

Photo credit: US Federal Bureau of Investigation, 1978. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain image.