15 May 2023

Fair to middling refers to something of acceptable, but not remarkable, quality, mediocre. The phrase begins to appear in print in the early 1820s, but from the context of those appearances must be somewhat older. The phrase probably got its start as a grade of commercial products or commodities, such as cotton, but from its earliest appearances in print it was also being used as jocular rankings of people.

Middling, meaning medium or moderate, especially used of something occupying an intermediate position between two extremes, is much older and Scottish in origin. The word appears as early as c.1420 in a Scottish manuscript on weights and measures:

The ynch sulde be with the thoum off midling mane nother our mikil nor our litil bot be tuyx the twa

The inch should be with the thumb of a middling man, neither over great nor over little but between the two

And we have this use of middling to refer to grades of meat in the Register of Privy Council of Scotland for 18 August 1550:

Nocht the les the mutoun is commonlie sauld upoun ane our hie price, and for remaidy heirof, it is divisit and ordanit that every mutoun be sauld of the prices following. The best moutoun for ix s, the midiling moutoun for viii s, and the worst moutoun for vii s.

(None the less, mutton is commonly sold at an over high price, and as a remedy hereof, it is devised and ordained that every mutton be sold at the following prices. The best mutton for 9 shillings, the middling mutton for 8 shillings, and the worst mutton for 7 shillings.)

At about this time middling starts appearing outside of Scotland.

Jump to 1821, and we see the first appearance of the phrase fair to middling. It’s in a supposed letter to the New England Galaxy of 2 March 1821 by someone with the improbable name of Diedrich Sapperment Van Wisem. It’s used in a question about the acting chops of Edmund Kean:

You are “requested to state,” whether, in all human probability, “Kelly’s Cambist” is not nearly “exhausted” by the Boston Weekly Report r[sic] and if you consider Mr. Kean’s acting to be of a quality from “middling to fair,” or “from fair to middling?”

Can you tell me the reason why “amateurs” are so blind when they sit in the pit?—When they sit in the boxes, third row, or gallery, they can see well enough—but when they condescend to sit in the pit, they wear spectacles.

The next year, we see fair to middling used in a modern commercial context as a grade of rice. From England’s Manchester Mercury of 16 July 1822:

The demand for Rice is very good, and the public sales have gone off with spirit at 13s for old, up to 14s 6d a 16s 3d per cwt. for fair to middling new: the quantity sold by public and private is 600 casks.

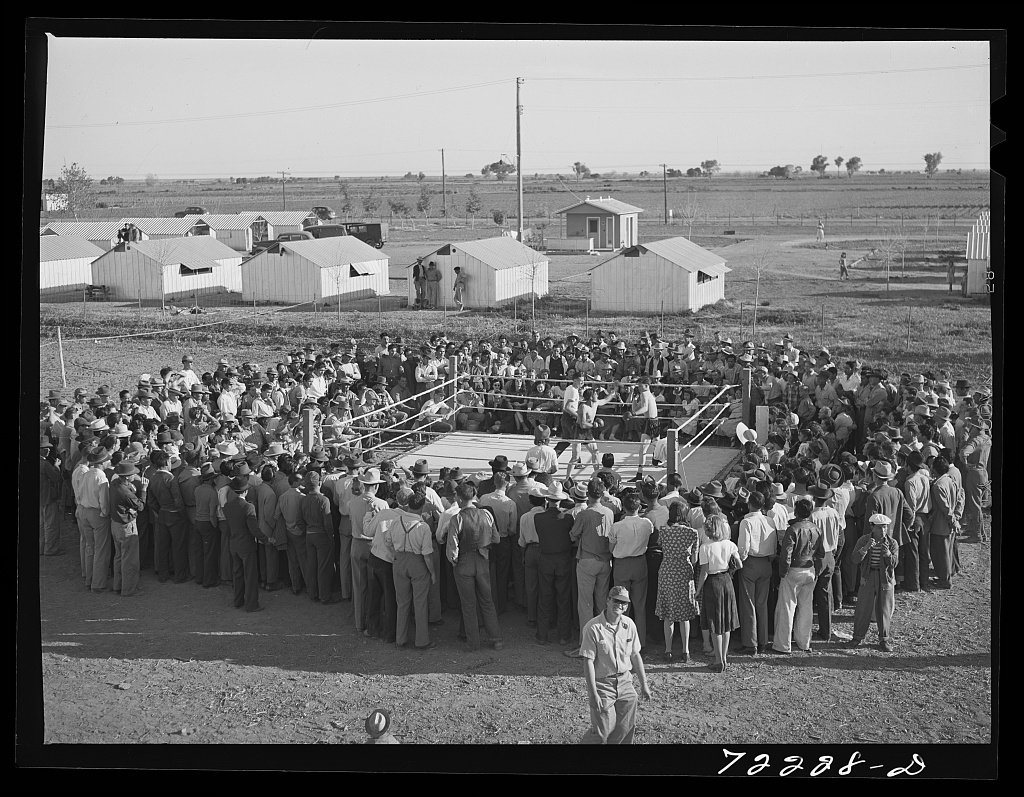

And it’s also in use in the United States, here seen in the Charleston, South Carolina City Gazette of 3 October 1822 as a grade of cotton:

The business of the week has been remarkably dull, and but few transactions in any description of produce have taken place—consequently, our quotations may be considered (with a few exceptions) nominal.

Cotton.—No transactions worthy of notice have taken place in this article during the week: sales for two or three small parcels only, of fair to middling, have been effected at our quotations.

Tobacco.—Sales of about one hundred hogsheads in small lots, of various qualities, at our prices, constitute (as far as we have been advised) the transactions of the week.

Whiskey appears to be advancing, several small lots have been sold at 40 cents.

A few days later the phrase appears as a ranking of politicians in the 9 October 1822 issue of the Boston Castigator. It’s in a humor piece masquerading as an advertisement for a public-relations “fixer.” I don’t know what, if any, particular scandal is being alluded to here (if anyone knows, by all means let me know):

ADVERTISEMENT EXTRA!

Monsieur Nong Tong Paw, Professor of President-making, Editor of “My Report,” &c. &c. direct from Paris tenders his service to the people of this ignorant country, in the line of his profession. N.B.—Any grand-father’s grand-son who should happen to get into a predicament from which his little wits cannot extricate him, can, by application as above, be screened from deserved public contempt. And any political renegade whose integrity should want whitewashing, can have the operation performed “weekly,” in so thorough a manner as to enable me to “report” him every Saturday evening, “from fair to middling.”

The following year we see it used as “grade” of marriageable women. From Boston’s Independent Microscope of 3 October 1823:

PRICES CURRENT.

Cattle Shows—plenty; the season just commencing.

Poultry—plenty, but principally in the hands of forestallers who purchase by the load, while the Clerk of the Market is seeking and prosecuting flying butchers, for selling meat in the vicinity of the Old Market.

Street walkers, of the feminine gender—very scarce, having generally taken lodgings in the House of Correction.

Ditto, of the masculine gender—plenty, and generally prowling about in darkness, seeking whom they may——destroy.

Young Ladies, candidates for matrimony—plenty, although quite bashful; upon the whole we may report from fair to middling.

Gamblers and Pickpockets—not very plenty now, many having gone to country Musters where some have eaught [sic] the hypo, which may probably prove dangerous; a few, however, are seen occasionally lurking about Merchant’s Hall and Ann street, in each of which places they have a rendezvous.

So that’s it. Middling got its start as a Scots adjective for something of intermediate quality. It entered into commercial usage as grade of product. At some point, probably in the early nineteenth century, the phrase fair to middling came into use in commercial contexts and was quickly taken up by American wits and jokesters to classify people.

Discuss this post