24 May 2023

Fuzz is an American slang term for the police. Today, we often associate the term with the 1960s counterculture, but it’s several decades older. Why the police were dubbed the fuzz is simply not known. All we know is the slang term began appearing in print in the 1930s. Here is the earliest example I know of, from the Los Angeles Times of 30 January 1924:

“But there’s only a few places that a ‘mob’ can work. That’s on street cars or in crowds on down-town streets. But the ‘cannon coppers’ here are too hep. A ‘mob’ can ‘beat a pap’ to the ‘leather’ and get away with it with the ordinary ‘fuzz’ lookin’ on. But it’s a twenty-to-one shot when the ‘cannon coppers’ are wise.” A mob in the parlance of the pickpocket is a gang of three or four pickpockets working together. The “wire” or the “gun” is the man who does the actual lifting of the victim’s money. A “pap,” if he is a man, is the victim. The other men who work with the “wire” are known as the “stalls.” The pickpockets refer to policemen in general as “the fuzz.”

(The cannon coppers, as explained elsewhere in the article, are police assigned to the anti-pickpocket detail. Why they are called this is not explained.)

Another example, from some six months later, appears in Chicago, as reported in the New York Times of 19 July 1924:

“Nix! A copper!” shouted one of the robbers as McGlynn appeared in a narrow passageway leading to the main offices of the plant.

“As soon as the fuzz puts his foot in the door, lay it into him,” ordered the leader.

Irwin’s 1930 American Tramp and Underworld Slang includes an entry for fuzz and even postulates an origin, although there is no evidence to suggest that his guess is correct:

FUZZ.—A detective; a prison guard or turnkey. Here it is likely that “fuzz” was originally “fuss,” one hard to please or over-particular.

It’s disappointing that we don’t have any idea where the term comes from, but that is the way of such slang words. Unless more early examples that provide a clearer context for the underlying metaphor, it is likely this origin will be lost to the ages.

Sources:

“Chicago Policeman Shot.” New York Times, 19 July 1924, 4/2. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, 2023, s.v. fuzz, n.1.

Irwin, Godfrey. American Tramp and Underworld Slang. New York: Sears, 1930. Reprint, Ann Arbor, Michigan: Gryphon Books, 1971, 81. Archive.org.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. fuzz, n.3.

“Pickpockets Dodging City.” Los Angeles Times, 30 January 1924, A3/2. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

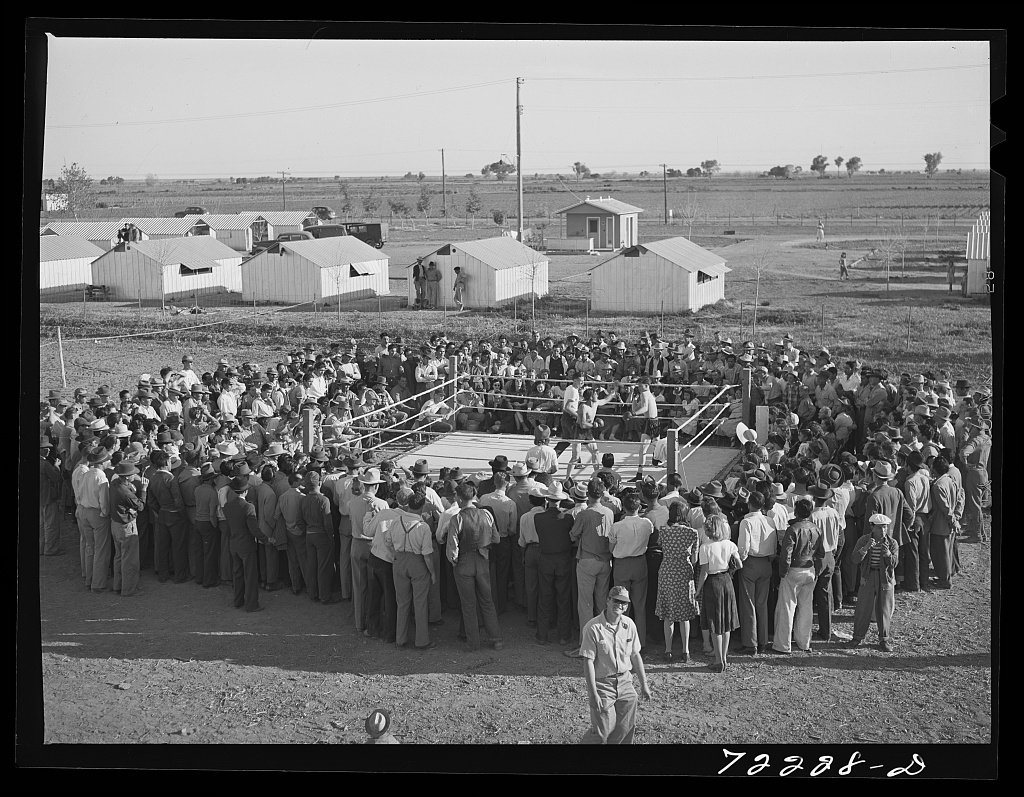

Photo credit. Mack Sennett Studios, 1914. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain image.