13 September 2023

Knock yourself out is a slang expression that is defined in this glossary of Ohio State University slang that appeared in the Columbus Sunday Dispatch on 24 November 1940:

Knock Yourself Out: To outdo oneself, put forth conspicuous energy, try to do numerous things at once. Used sarcastically to deride meager effort of another, i.e., “Don’t knock yourself out.”

Contrary to what one may think, the slang phrase has nothing to do with boxing, although one can find literal uses of the phrase relating to that and other contact sports, like American football and rugby. Instead, the metaphor is one of working yourself to exhaustion. The Oxford English Dictionary and Green’s Dictionary of Slang both mark the phrase as US in origin, but the earliest citation I have found is from the Port Adelaide News in South Australia on 17 April 1924:

Young Wife—“I’ve just polished it, and it looks so nice. I thought you’d like it.”

Young Husband—“Like it? When I’m afraid to walk on it? I don’t know why you want to knock yourself out polishing floors so a man can’t walk on ‘em.”

The earliest American use that I have found is from ten years later in the Las Vegas Daily Optic of 29 March 1934. That’s Las Vegas, New Mexico, not the more famous city in Nevada. The article in question is about caring for a terminally ill friend:

You have known, perhaps, what it is to watch long at the death bed of a dear friend.

[…]

Your friend kept telling you that you would knock yourself out, that there was nothing you could [do] for the sufferer.

Knock yourself out is often uttered as a means of telling some to go ahead and diligently try to do something, implying the task is either unimportant or has little chance of success. We see this usage in the Pittsburgh Courier of 23 April 1938 describing temperance battles in Los Angeles:

The wets and the drys are battling here. The wets have it. But the drys are gaining ground. Knock yourself out. The wets are simply lush heads, and the drys are the tea hounds.

By the end of the 1930s, the phrase starts appearing with much more frequency, in particular among musicians. Here is one from the Buffalo Evening News of 25 November 1939:

Johnny Green is probably the busiest young maestro in radio.

He does three commercial broadcasts on the three major networks over 200 different stations each week. But that’s only the beginning.

He also conducts for special dance dates, is ever busy with new compositions, and constanly [sic] improves his technique as a piano soloist.

“Why do you knock yourself out this way?” a friend asked.

“You’ve got to do it or else you become just another bandleader,” Johnny replied. “Besides, I enjoy the work, believe it or not."

And this from the Sul Ross Skyline of 28 February 1940, the school newspaper of the teacher’s college in Alpine Texas:

For the benefit of you school teachers who are getting the swing fever, the following definitions will clear up a few miss-understandings [sic]: “Knock yourself out;” “In the groove; “Getting your kicks.” Translated to English as meaning the high and happy feeling one gets while listening to swing tempo.

So by 1940, this phrase which appears to have gotten its start in Australia some fifteen years earlier, was in common slang use throughout the United States.

Sources:

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, 2023, s.v. knock out, v.

Morris, Earl J. “Grand Town Day.” Pittsburgh Courier (Pennsylvania), 23 April 1938, 21/2. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

“Musician’s Kicks.” Sul Ross Skyline (Alpine, Texas), 28 February 1940, 2/4. NewspaperArchive.com

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. knock, v.

Stailey, Bob. “Campus Slanguage Goes Wacky.” Columbus Sunday Dispatch (Ohio), 24 November 1940, Magazine Section (no page numbers; image 85/4). Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

“Three Programs Keep Green Busy.” Buffalo Evening News (New York), 25 November 1939, 5/6. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Vivian, Walter[?]. “Along the Banks of the Gallinas.” Las Vegas Daily Optic (New Mexico), 29 March 1934, 2/2. NewspaperArchive.com. The scan of this page is very poor, and I have guessed at much of the punctuation and the author’s first name.

“Week In…Week Out.” Port Adelaide News (South Australia), 17 April 1924, 8/2. NewspaperArchive.com.

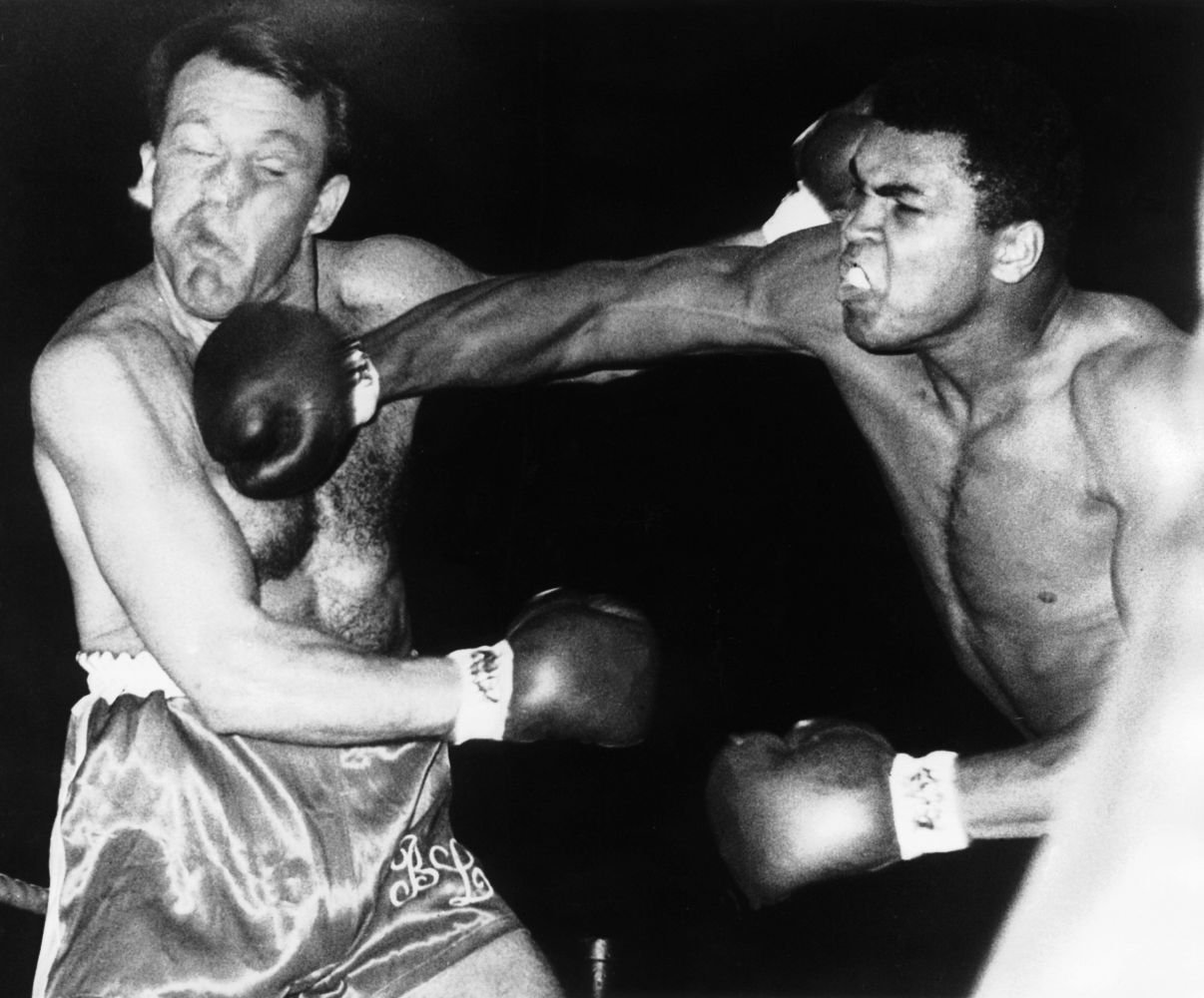

Photo credit: unknown photographer, 1966. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain image.