27 September 2023

Geek is a general term of opprobrium that has, over the centuries, developed some specialized senses. And while it is generally negative, in some contexts it has been reclaimed as a proud marker of identity.

The word dates to the sixteenth century when it had the sense of a fool or simpleton. It was generally spelled geck, with variations being common. We see it Alexander Barclay’s 1530 Ecloges:

And he is a fole / a sot and a geke also

Whiche choseth a place / vnto the same to go

And where dyuers ways / lead thether dyrectly

He chosed the worst / and moost of Jeopardy

Shakespeare uses the word in two of his plays. In Twelfth Night, composed c.1601 and first published in the 1623 First Folio, the character of Malvolio, a servant, uses it in speaking to Olivia, his mistress:

Why haue you suffer’d me to be imprison’d,

Kept in a darke house, visited by the Priest,

And made the most notorious gecke and gull

That ere inuention plaid on? Tell me why?

And in Cymbelene, which was first staged no later than 1611 and again first published in the First Folio, the ghost of Sicilius Leonatus uses the word in speaking to Posthumus, his son:

Why did you suffer Iachimo, slight thing of Italy, To taint his nobler hart & brain, with needlesse ielousy, And to become the geeke and scorne o’th’others vilany?

This general sense of a worthless or despised individual persisted through the nineteenth century. And in the latter half of that century geek starts appearing in American slang. The Oxford English Dictionary treats the British geck and the American geek as distinct words, presumably because of the difference in pronunciation, with geek being a variant on the older word. Geck being pronounced /ɡɛk/, and geek being pronounced /ɡik/. In recent decades, the American pronunciation of geek has recrossed the Atlantic to colonize the mother country.

In the early twentieth century, the American term developed a specific meaning in the carnival or circus world, that of a performer who would eat live animals or do other repellant or painful things on stage—or more usually feign doing so. The earliest use of this specialized sense that I’m aware of is in an advertisement in the entertainment newspaper Billboard of 18 May 1918:

WANTED FOR THE GREAT WORTHAM CIRCUS SIDE SHOW

Strong Freak or Attraction for a single Pit or Platform Show, either on salary or per cent. No salary too high or no attraction too strong. Ten big fairs to get the money at. I want a real Geek, man or woman, for my Snake Show.

A 1931 American Speech glossary of circus and carnival slang gives a putative origin for this particular sense:

geek, n. A freak, usually a fake, who is one of the attractions in a pit-show. The word is reputed to have originated with a man named Wagner of Charleston, W. Va., whose hideous snake-eating act made him famous. Old timers still remember his ballyhoo, part of which ran:

“Come and see Esau

Sittin’ on a see-saw

Eatin’ ’em raw!”

Wagner’s act certainly helped popularize this sense of the word, but whether or not he was the origin is anyone’s guess.

Note, that geek’s general use to refer to someone deserving of opprobrium continued to be the more common sense of the word; the carnival sense did not replace it. And another specialized sense, more common than the carnival sense at the time but less well known today, is that of a weak man, especially one prone to various ailments or even hypochondria. Here is an example from a newspaper article on hemorrhoids that appeared in the Colorado Springs Gazette of 2 January 1920:

When the inflammation subsides, as it does in a few days, as a rule, the pile still remains, of course, altho [sic] many a poor geek at this time gives a testimonial to the effect that whatever treatment he used has “cured” his piles—and by the time his next attack comes the testimonial is embalmed in indelible printer’s ink.

This sub-sense of a weak and sickly man continued well into the 1950s, often in the phrase poor geek. And it is probably from this sub-sense that the sense of an overly bookish, non-athletically inclined student developed. Both the Oxford English Dictionary and Green’s Dictionary of Slang list the first use of this studious sense as being by writer Jack Kerouac in a 1 October 1957 letter to Allen Ginsberg:

Unbelievable number of events almost impossible to remember, including earlier big Viking Press hotel room with thousands of screaming interviewers and Road roll original 100 miles of ms. rolled out on carpet, bottles of Old Granddad, big articles in Sat. Review, in World Telly, everyfuckingwhere, everybody mad, Brooklyn College wanted me to lecture to eager students and big geek questions to answer.

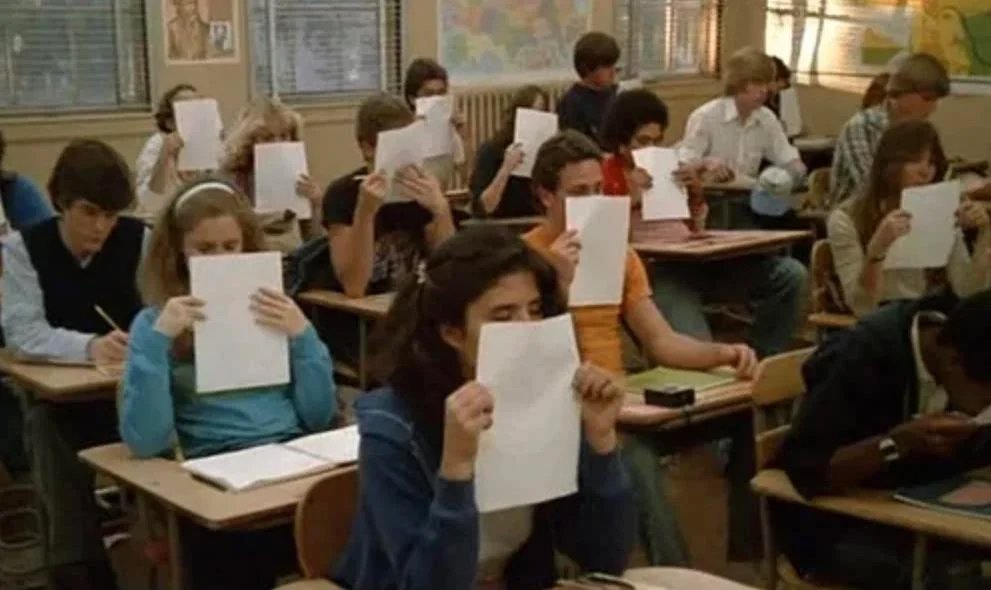

But as one can see from the context, the meaning of Kerouac’s geek isn’t clear. Additionally, his use here would be a very early example. The use of geek to mean a studious student would not become common until the 1980s. Kerouac could have meant questions from studious Brooklyn College students, or he could have just meant that he had to answer a lot of foolish questions from all sorts of people.

Early use of the studious sense was often in the slang of Black youth, before it transferred over to university slang in general. For instance, we have this entry in a glossary of Black teen slang in Edith Folb’s 1980 Runnin’ Down Some Lines:

geek 1. Weird, unusual, or different person. 2. Studious person.

And with the advent of the personal computer in the early 1980s, the studious sense of geek became attached to the world of high-tech. A user posted the following to the Usenet group net.misc on 16 February 1983:

I eschew the use of “foo” “bar” and other dill-beak geek dull unimaginative temporary filenames!

And Eric Raymond’s 1991 New Hacker’s Dictionary included this entry:

computer geek, n. One who eats (computer) bugs for a living. One who fulfills all the dreariest negative stereotypes about hackers: an asocial, malodorous, pasty-faced monomaniac with all the personality of a cheese grater. Cannot be used by outsiders without implied insult to all hackers; compare black-on-black usage of ‘n[——]r’. A computer geek may be either a fundamentally clueless individual or a proto-hacker in larval stage. Also called turbo nerd, turbo geek.

Despite Raymond’s allusion to the carnival sense of geek, there is no reason to think that the tech (or any other) sense of geek derives from the carnival one. Rather the various specialized senses all developed independently from the general term of opprobrium.

As seen in these last two quotations, the tech sense started out as a negative one. But by the late 1990s geek would be reclaimed and used proudly by computer engineers, coders, and other technical specialists.

Sources:

Advertisement. The Billboard, 18 May 1918, 29. ProQuest Magazine.

Barclay, Alexander. Ecloges. London: P. Treveris, 1530, sig. Ciii-v. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Brady, William. “Health Talks.” Colorado Springs Gazette, 2 January 1920, 4/6. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Folb, Edith A. Runnin’ Down Some Lines: The Language and Culture of Black Teenagers. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard UP, 1980, 239. Archive.org.

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, 2023, s.v. geek, n.1.

Kerouac, Jack. Selected Letters: 1957–1969. Ann Charters, ed. New York: Viking, 1999, 66.

Maurer, David W. “A Glossary of Circus and Carnival Slang.” American Speech, 6.5, June 1931, 327–337 at 331. JSTOR.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. geck, n.1.; third edition, March 2003, s.v. geek, n.

Raymond, Eric S. The New Hacker’s Dictionary. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1991, 102. Archive.org.

Shakespeare, William. Cymbelene. In Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies. London: Isaac Jaggard and Edward Blount, 1623, 5.4, 393–93. Folger Shakespeare Library.

———. Twelfth Night. In Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies. London: Isaac Jaggard and Edward Blount, 1623, 5.1, 275/1. Folger Shakespeare Library.

Photo credit: Charles Hutchins, 2007. Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.