30 October 2023

The word gonzo is inextricably linked to writer Hunter S. Thompson, famed for his style dubbed gonzo journalism. Gonzo is a highly subjective, first-person style, characterized by distorted and exaggerated facts. From this name for a journalistic style, the word quickly shifted in meaning to refer to anything eccentric, bizarre, or out of control. Thompson first used the word in print on 11 November 1971 in his book Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, which first appeared serialized in the pages of Rolling Stone magazine:

“Right,” I said. “But first we need the car. And after that, the cocaine. And then the tape recorder, for special music, and some Acapulco shirts.” The only way to prepare for a trip like this, I felt, was to dress up like human peacocks and get crazy, then screech off across the desert and cover the story. Never lose sight of the primary responsibility.

But what was the story? Nobody had bothered to say. So we would have to drum it up on our own. Free Enterprise. The American Dream. Horatio Alger gone mad on drugs in Las Vegas. Do it now: pure Gonzo journalism.

When asked where the word came from, Thompson would credit editor Bill Cardoso with coining the word in 1970 in a conversation with him about his article “The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved” which appeared in Scanlon’s Monthly that year. For instance, a 1977 interview on the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation has this exchange between Thompson and the interviewer:

Gzowski: Where did the word “Gonzo” come from?

HST: It’s an old Boston street word. It’s one of the Charles River things that started when you’re twelve years old on the banks of the Charles River. “Gonzo” is a word that Bill Cardoso, who’s an editor at the Boston Globe, came up with to describe some of my writing. I just liked it. And I thought, “Well, am I a new journalist? Am I a political journalist?” I’m a Gonzo journalist … And why not?

And in another 1977 interview, this time with High Times magazine, Thompson said:

One of the letters came from Bill Cardozo, who was the editor of the Boston Globe Sunday Magazine at the time. I’d heard him use the word Gonzo when I covered the New Hampshire primary in ’68 with him. It meant sort of “crazy,” “off-the-wall”—a phrase that I always associate with Oakland. But Cardozo said something like, “Forget all the shit you’ve been writing, this is it; this is pure Gonzo. If this is a start, keep rolling.” Gonzo. Yeah, of course. That’s what I was doing all the time. Of course, I might be crazy.

While it is all but certain that Cardoso was the first to apply gonzo to Thompson’s style of journalism, where Cardoso got the word is very much up in the air. Cardoso said it was a South Boston slang term for “guts and stamina of the last man standing at the end of a marathon drinking bout.” But it does not appear to be a Boston slang term, or at least there is no record of any such word. On another occasion, Cardoso claimed that it came from the French Canadian gonzeaux, meaning “shining path.” That too is a fiction, as if Cardoso was creating a gonzo etymology for gonzo.

Corey Seymour and Jann Wenner’s 2007 Gonzo: The Life of Hunter S. Thompson gives a different story about the origins of the term from Doug Brinkley, the literary executor of Thompson’s estate:

The Internet is full of bogus falsehoods propagated by uninformed English professors and pot-smoking fans about the etymological origins of “gonzo.” Here’s how it happened: The legendary New Orleans piano player James Booker recorded an instrumental song called “Gonzo” in 1960. The term “gonzo” was Cajun slang that had floated around the French Quarter jazz scene for decades and meant, roughly, “to play unhinged.” The actual studio recording of “Gonzo” took place in Houston, and when Hunter first heard the song he went bonkers—especially for this wild flute part. From 1960 to 1969—until Herbie Mann recorded another flute triumph, “Battle Hymn of the Republic”—Booker’s “Gonzo” was Hunter’s favorite song.

When Nixon ran for president in 1968, Hunter had an assignment to cover him for Pageant and found himself holed up in a New Hampshire motel with a columnist from the Boston Globe Magazine named Bill Cardoso. Hunter had brought a cassette of Booker’s music and played “Gonzo” over, and over—it drove Cardoso crazy, and that night, Cardoso jokingly derided Hunter as “the ‘Gonzo’ man.” Later, when Hunter sent Cardoso his Kentucky Derby piece, he got a note back saying something like, “Hunter, that was pure Gonzo journalism!” Cardoso claimed that the term was also used in Boston bars to mean “the last man standing,” but Hunter told me that he never really believed Cardoso on this. Just another example of “Cardoso bullshit” he said.

The bit of it being Cajun slang or Louisiana jazz jargon is unsubstantiated. I have found no uses of the word in relation to Louisiana until the appearance of Booker’s tune in 1960. But the rest of Brinkley’s tale seems plausible and match, in the essential elements, the accounts of the word’s origin that Thompson gave. But Thompson is not exactly a reliable source, and it seems that Brinkley’s main source is Thompson, so take it with a grain of salt.

But if we take Brinkley’s story as true, where did Booker get the name of his song from? According to a February 2002 article in BluesNotes magazine by Greg Johnson, James Booker took the name of his song from a character in the 1960 film The Pusher. That movie is based on Ed McBain’s (pseud. Evan Hunter) 1956 novel of the same name. In the novel, the character receives his nickname as a mishearing of the slang word gunsel, a gunman:

We know what happened at the card game. We know all about the gunsel routine and the way your goofed and called it “gonzo” and the way it brought down the house, and the way you were called Gonzo the rest of the night. Batman told us all about it, and Batman’ll swear to it. We figure the rest like this, pal. We figure you used the Gonzo tag when you took over the Hernandez’s trade because you didn’t figure it was wise to identify your own name with your identity as a pusher. Okay, so these kids were looking for Gonzo, and they found him, and one them bought a sixteenth from you, and he’ll swear to that too.

But as with the other stories, we have little substantiation that the word comes from the McBain novel.

Dictionaries have attempted to give gonzo an etymology, but like the above stories, they cannot be trusted. The Oxford English Dictionary says it is “perhaps a borrowing from Italian,” giving either the Italian gonzo, meaning foolish, or the Spanish ganso, meaning goose or fool, as the etymon. While Green’s Dictionary of Slang gives a more complex etymology, saying it is either a blend of gone + crazo (an eccentric person) or gone + the Italian suffix -zo, with an allusion to gung-ho. These explanations are plausible but seem be by etymologists using traditional tools of etymology, borrowing and derivation, to reach for an answer that is simply not known.

What we can say for certain about the origin of gonzo, as we know it today, is that it was coined by Cardoso, and beyond that no one can say.

Sources:

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, n.d., s.v. gonzo, adj.1.

Gzowski, Peter. 90 Minutes Live, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 12 April 1977. In Anita Thompson, ed. Ancient Gonzo Wisdom: Interviews with Hunter S. Thompson. Cambridge, MA, Da Capo Press, 2009, 70–71. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Hirst, Martin. “What is Gonzo? The Etymology of an Urban Legend.” University of Queensland, Australia, 19 January 2004.

McBain, Ed (pseud. Evan Hunter). The Pusher (1956). New York: Penguin, 1963, 149. Archive.org.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. gonzo, adj. & n.

Rosenbaum, Ron. “Hunter S. Thompson: The Good Doctor Tells All … About Carter, Cocaine, Adrenaline, and the Birth of Gonzo Journalism.” High Times, September 1977. In Anita Thompson, ed. Ancient Gonzo Wisdom: Interviews with Hunter S. Thompson. Cambridge, MA, Da Capo Press, 2009, 91–92. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Thompson, Hunter S. (Raoul Duke, pseud.). “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.” Rolling Stone, 11 November 1971, 36–48 at 38/4. ProQuest Magazines.

Wenner, Jann S. and Corey Seymour. Gonzo: The Life of Hunter S. Thompson. New York: Little, Brown, 2007, 125–26.

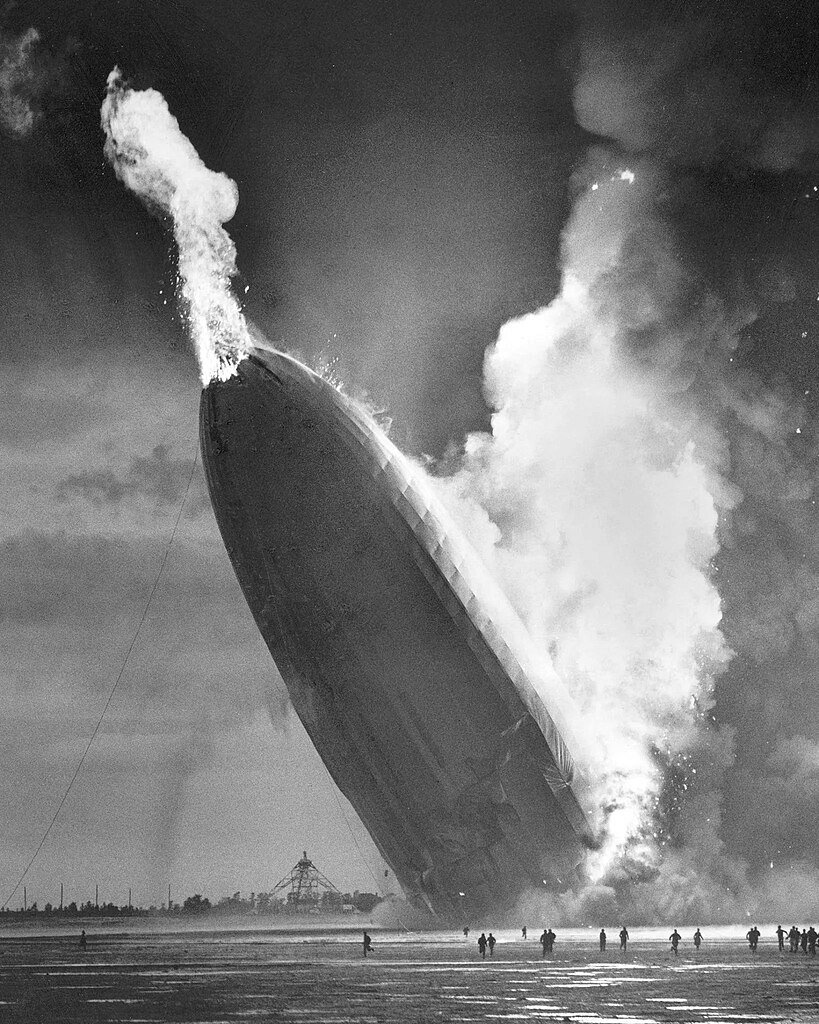

Image credit: Ralph Steadman, 1971. Fair use to illustrate the topic under discussion.