1 November 2023

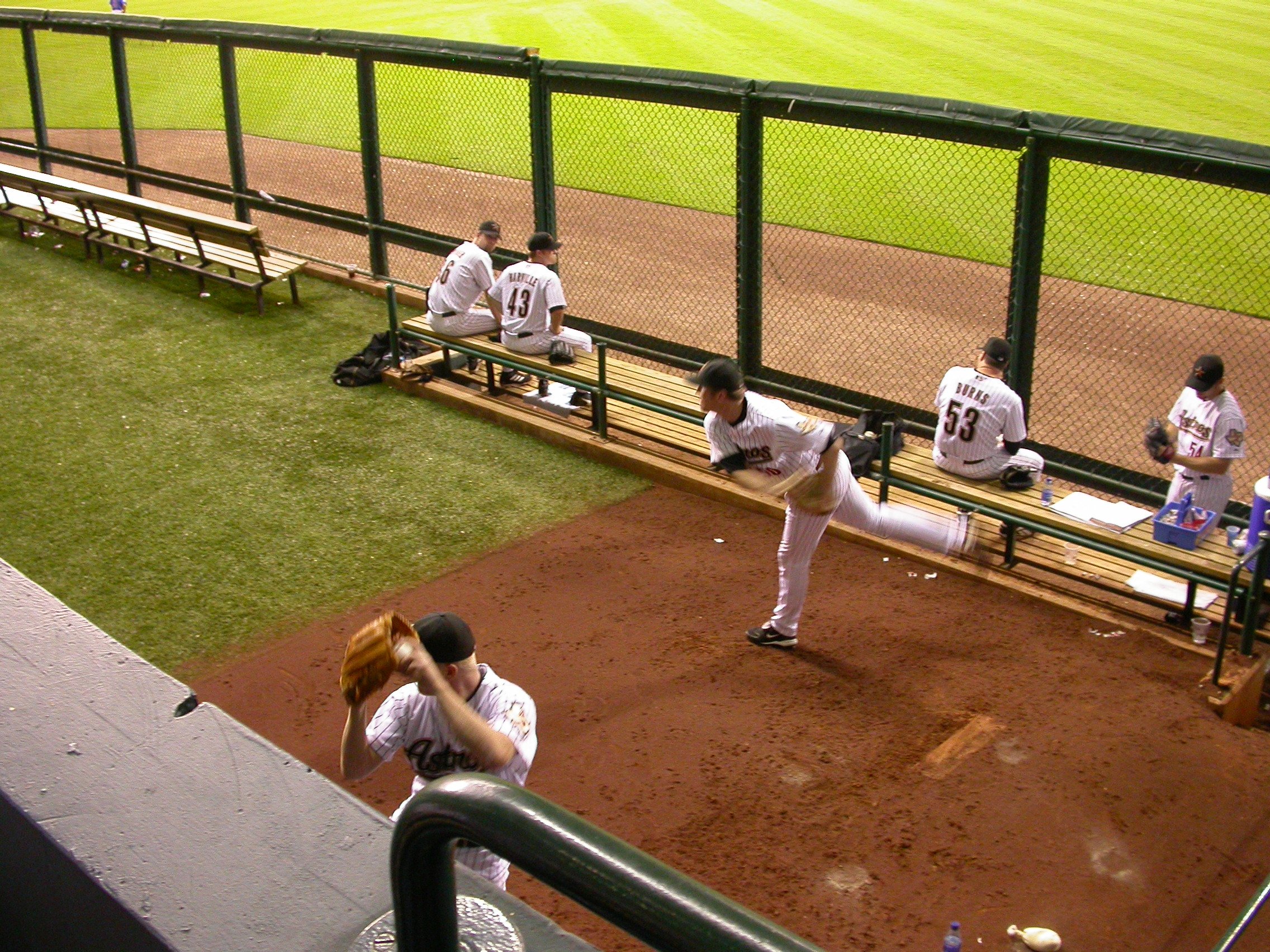

One of the mysteries of the game of baseball is the origin of the term bullpen, the name for the area in which relief pitchers warm up. Several competing hypotheses vie for the origin. Of the hypotheses, the most likely is that it stems from an older use of bullpen to mean a holding area or jail.

Of course, the collocation of the words bull and pen to literally mean a place where male bovines are kept goes back centuries. But in the early nineteenth century, bullpen became an American slang term for a jail or holding area. The first known use of this sense is in Peter Horry and Mason Locke “Parson” Weems’s 1809 biography of American Revolutionary War hero Francis Marion:

The tories were all handcuffed two and two, and confined together under a centinel, in what was called a bull-pen, made of pine trees, cut down so judgmatically as to form, by their fall, a pen or enclosure.

This sense of bullpen as jail can be found in American writing to this day.

The association with baseball starts in the late nineteenth century, but in a different sense than that of a pitcher’s warm-up area. Instead, bullpen was the term used for a roped-off area in foul territory or in the outfield for standing-room-only crowds who were admitted to the park at a discount. From the Cincinnati Enquirer of 9 May 1877:

The bull-pen at the Cincinnati Grounds, with its “three-for-a-quarter” crowd, has lost its usefulness. The bleaching boards just north of the north pavilion now hold the cheap crowd which comes in at the end of the first inning on a discount.

One might think that bullpen comes from the idea that it is a holding area for relief pitchers, but this 1877 citation removes that possibility. It appears over a decade before player substitutions and relief pitchers were allowed. Instead, as the above quotation indicates, bullpen presumably comes from the idea of a holding area for the fans with cheap tickets. Later, when relief pitchers were allowed by the rules, their warm-up area was often located where the old bullpen for the crowd had been located. In the early twentieth century, the name would get a boost by the presence of large signs on the outfield fences advertising Bull Durham tobacco. These signs had become ubiquitous in ball fields c. 1910, which is about the time that bullpen acquired the sense of a pitcher’s warm-up area.

In the 19 March 1910 Cincinnati Post we get a list of Reds’ players’ nicknames that includes pitcher Tom Cantwell, who is dubbed “The Bullpen Kid.” Cantwell did not last long in the major leagues, and the nickname may be a reference to him not getting much playing time with the Reds.

The next year we get the first unambiguous use of bullpen in the baseball sense we know today. That comes in the 19 June 1911 Minneapolis Morning Tribune:

Joe Cantillon will probably send either Rube Waddell or Roy Patterson to the firing line today in an attempt to grab the final game of the series from the Senators. Waddell was kept out in the center field bullpen most of the afternoon warming up, while Patterson returned from a brief scouting trip down through Kentucky.

Eight months later, in the 12 February 1912 Fort Worth Star-Telegram, we see this discussion of outfielder Josh Devore, who at the time was playing for the New York Giants under manager John McGraw. The passage in question refers back to events of 1908 when he played for the Meridian, Mississippi Ribboners:

While with Meridian a newspaperman saw him perform and urged Manager McGraw to purchase him, which he did. Muggsy sent the young fielder over to the Newark bullpen, as the Eastern League grounds are called, to get a little seasoning under “Big Chief” Stallings.

Devore moved to the Newark Indians in 1908, and in September of that year made his major league debut with McGraw’s Giants. The question here is whether bullpen was an actual nickname for Newark’s Wiedenmayer’s Park, or if it is a reference to McGraw using the Newark club as a farm team to “warm up” inexperienced players before they were promoted to the Giants.

That’s it. The most likely explanation is that baseball’s bullpen started off as a specialized sense of the word’s meaning as a holding area, first for prisoners and then as fans. It may have been reinforced by advertisements for Bull Durham tobacco that were located near the areas where pitchers warmed up.

But we can’t let it go without including the wisdom, almost certainly factually incorrect, of baseball legend Casey Stengel, who held forth on the etymology in the 10 March 1967 New York Times:

Why is a bull pen called a bull pen in baseball!

“You could look it up and get 80 different answers,” Casey Stengel said today, “but we used to have pitchers who could pitch 50 or 60 games a year and the extra pitchers would just sit around shooting the bull, and no manager wanted all that gabbing on the bench.

“So he put them in this kind of pen in the outfield to warm up, it looked like a place to keep cows or bulls.”

Sources:

“BASE-BALL. The Battle for the League Pennant Opened.” Cincinnati Enquirer (Ohio), 9 May 1877, 2/5. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

“Big League Stars Who Will Be Seen in Texas This Spring.” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, 21 February 1912, 8/5. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Dickson, Paul. The Dickson Baseball Dictionary, third edition. New York: W.W. Norton, 2009, 143–46, s.v. bullpen.

Durso, Joseph. “Bull Pen of Mets is a ‘Disaster Area’” (9 March 1967). New York Times, 10 March 1967, 44/7. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

“Floto’s Column.” Denver Post (Colorado), 6 May 1905, 8/7. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, n.d., s.v. bullpen, n.

“‘Handles’ Reds Bear on Field of Action.” 19 March 1910, Cincinnati Post (Ohio), 6/3. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Horry, P. and M. L. Weems. The Life of Gen. Francis Marion (1809). Philadelphia: Joseph Allen, 1829, 225. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. bullpen, n.

“Senators Win Second in Ninth Inning Rally.” Minneapolis Morning Tribune (Minnesota), 29 June 1911, 14/4–5. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Image credit: D. L., 2005. Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.