14 February 2024

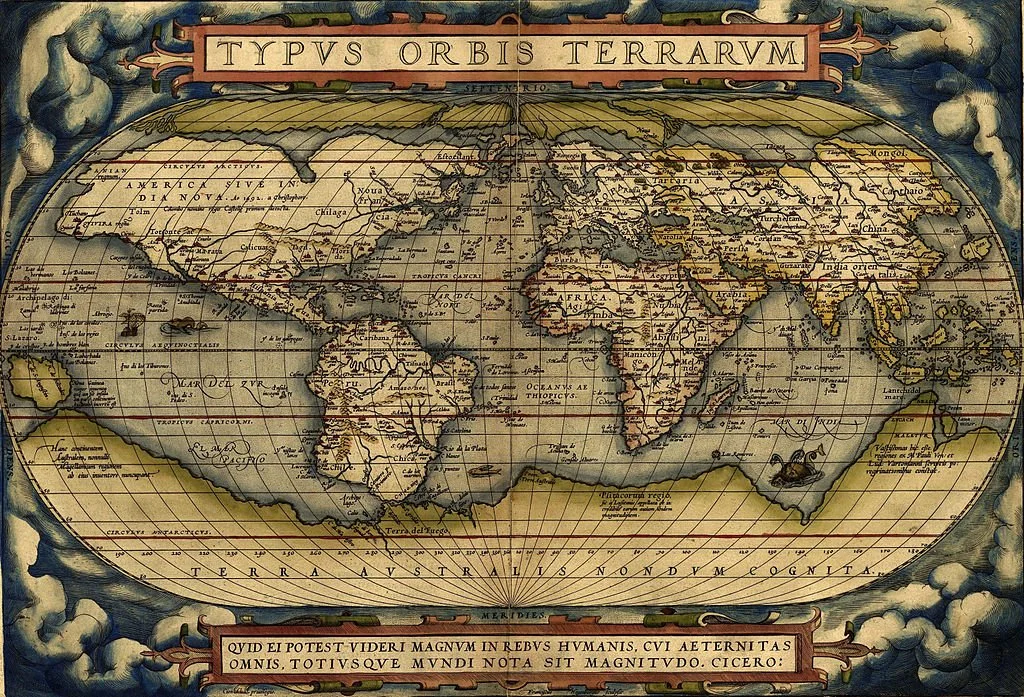

The continent of Australia gets its name, appropriately enough, from the Latin australis, meaning southern. And the name Terra australis incognita (unknown southern land) has been applied to hypothetical southern continents since antiquity. There is no all-encompassing Indigenous name for the continent; instead there is a wide variety of local names for its different regions.

The first European to visit the continent we know today as Australia was Willem Janszoon in 1606. He dubbed the land Nieu Zelant, after the Dutch province of Zeeland, but the name was not generally adopted. The name New Zealand was later applied to Aotearoa by European settler-colonists of those islands. A second Dutch explorer, Dirck Hartog, landed on the continent in 1616. He called the land Eendrachtsland, after his ship, the Eendracht (Unity or Concord), but again the name did not catch on.

A third Dutchman, Abel Tasman, was the first to give the continent a lasting name. He made two voyages to the South Seas for the Dutch East India Company, in 1642–43 and again in 1644. On this second expedition he named the continent Nieuw-Holland (New Holland), a name that lasted for some while. The island of Tasmania is named after him. (Tasman had dubbed that island Van Diemen’s Land, after Antonio Van Diemen, governor-general of the Dutch East Indies.)

The name Australia was first applied to the continent in an English translation of a work by Gabriel de Foigny. De Foigny, under the pseudonym Jacques Sadeur, published two books about the continent. The first was the 1676 La Terre australe connue (The Southern Lands, Known). The preface to the second book in 1692, Les avantures de Jacques Sadeur dans la découverte et le voyage de la terre austral (The Adventures of Jacques Sadeur in the Discovery of and Voyage to the Southern Land), contains this passage:

Il est encore vrai qu’en comparant la Description que nous a fait de la Terre Australe Fernandes de Quir, Portugais, avec celle qu’on va lire, on est oblige d’avoüer qu’il saut qu’il en ait découvert quelque chose: Car nous lisons en sa huiriéme Requeste au Roi d’Espagne, que dans les découvertes qu’il sit l’an 1610, de la Terre Australe, il trouva un Païs beaucoup plus fertile & plus people que tous ceux de l’Europe.

While in the original French de Foigny simply called it la terre australe (the southern lands) The English translation of this passage, published in 1693, adds the name Australia:

It is likewise true, that upon comparing the Description that Ferdinando de Quir a Portugal, gives of the Southern Continent, with that which is contained in this Book, it must needs be allowed, that he hath made some Discovery of that Country. For we read in his eighth Request to the King of Spain, that in the Discoveries, which he made in the year 1610, of the Southern Country, called here Australia, he found a Country much more Fertile and Populous than any in Europe.

The passage mentions Pedro Fernandes de Queirós, who commanded a 1605–06 expedition under the Spanish flag, to find Terra australis. While he did map much of the Pacific, he did not find the continent. Although his second-in-command, Luis Váez de Torres sailed almost within sight of it while circumnavigating the island that is now known as New Guinea. The Torres Strait between New Guinea and Australia is named for him.

The name Australia was officially adopted by the British Admiralty as the name for the continent in 1824 following the 1814 publication of Matthew Flinders’s account of his 1802–03 voyage circumnavigating the continent. Flinders was the first to identify Australia as a continent.

Sources:

Everett-Heath, John. Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Place Names, sixth ed. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2020, s.v. Australia, Tasmania. Oxfordreference.com.

de Foigny, Gabriel [Jacques Sadeur, pseud.]. La Terre austral connue. Paris: Jacques Verneuil, 1676. Bibliothèque Nationale de France: Gallica.

———. Les avantures de Jacques Sadeur dans la découverte et le voyage de la terre australe. Paris: Claude Barbin, 1692, sig. a.iiii.verso–a.v.recto. Bibliothèque Nationale de France: Gallica.

———. A New Discovery of Terra Incognita Australis, or the Southern World. London: John Dunton, 1693, n.p. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

“Life in Australia.” Australian Government, Department of Immigration and Citizenship, 2007. Archive.org.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. Australian, n. and adj.

“Where Did the Name ‘Australia’ Come From?” National Library of Australia. n.d. (accessed 12 January 2024).

Image credit: Abraham Ortelius, 1570. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain image as a mechanical reproduction of a public domain work.