28 June 2021

[28 February 2024: added information about the 1989 t-shirt]

Critical race theory (CRT) is nothing new. The term itself is over thirty years old, and the school of thought has its roots in the early 1970s, making it around fifty years old. Different researchers take different approaches to the topic, and there is no single, agreed definition of what exactly constitutes critical race theory, but it is essentially a lens for examining how present-day institutional power structures serve to benefit white people over Black people.

The key element in critical race theory is that it posits that the procedures and substance of American institutions and law are structured, wittingly or unwittingly, to maintain white privilege. More specifically, there are several tenets of critical race theory that most scholars working the field would agree with:

Race is a social construction, not a biological one.

“Color-blind” laws and institutions tend to marginalize and obscure inequality; therefore, race should be made visible.

Interest convergence. Reforms that are intended to benefit minorities tend to only happen when they also benefit the white majority.

Intersectionality. Inequality and subordination operate on multiple axes (e.g., race, class, gender, sexuality, etc.; a Black, working-class woman’s experience of oppression is different from that of a white, working-class woman or a Black, professional man.

And just as there is no universally accepted definition, there is no single methodology that CRT scholars use, but many use narrative and story-telling to make visible inequality and oppression and their effects. Critical race theory may be taught in some undergraduate-level university classes, but it is primarily found only at the graduate level. It is not found in primary or secondary education.

There are some right-wing political activists who use the term critical race theory as a political boogeyman to cater to the fears of the white majority in America and advance a racist political agenda. Their strawman of critical race theory bears little or no resemblance to CRT as it is actually studied. It attempts to define CRT as encompassing any discussions of race or racism in the United States today or in its history, and it claims the purpose of CRT is to disparage the United States and white Americans. This strawman, which is not a critique of CRT as it is actually practiced, arose as a response to the New York Times 1619 Project, which on the 400th anniversary of the introduction of slavery to North America produced primary and secondary school teaching materials about the history of slavery and racial oppression in the United States.

The critical in the name comes out of the social philosophy of Critical Theory, which examines society and culture to reveal and challenge power structures. Critical Theory was championed by the Frankfurt school of philosophy in the 1930s and 40s, especially the writings of Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno, and was further developed in the 1960s by Jürgen Habermas and others.

Beginning in the early 1970s, a group of scholars, including Derrick Bell, Mari Matsuda, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Richard Delgado, Kendall Thomas, Patricia Williams, and Neil Gotanda, started extending critical theory into the law, but with a focus on race, formulating what would become known as critical legal studies (CLS).

But critical legal studies and the subsequent critical race theory diverge sharply from their progenitor, Critical Theory. For one, they focus on race, which is absent from Critical Theory, and they do not focus on social class and economics as primary factors in their analysis. (Class and economics can enter into critical race theory via intersectionality, but they are not the core focus.) Furthermore, both CLS and CRT differ from the modernist Critical Theory in that they abandon the universalist and teleological Marxist elements of the latter in favor of a more localized and relative approach. They are post-modern schools of thought in that they seek to situate power structures and inequality in particular and dynamic historical and cultural contexts. Therefore, the labeling of critical race theory as Marxist, as many critics of the approaches do, is incorrect. Critical race theory doesn’t even fit the loosest definition of Marxist, that is analysis that focuses on social class and economics.

Derrick Bell’s 1973 book Race, Racism, and American Law, is the foundational document in critical legal studies, but that book doesn’t use the term itself. The phrase critical legal scholars is in place by 1982, when it appears in the May issue of the Harvard Law Review:

The discipline’s growing self-consciousness is largely attributable to the critical legal scholars, a small group of academics who emerged as a self-identified school in the late 1970’s.

And another Harvard Law Review article, this one a review of Derrick Bell’s And We Are Not Saved: The Elusive Quest for Racial Justice from February 1988, uses the phrase critical legal studies and gives an apt definition:

The central tenet of the critical legal studies movement—insofar as there is one—is that law and legal consciousness mask the collective choices implicit in existing social arrangements. By making institutions appear fair and rational, law induces ideological consent to hierarchical systems. Litigation and legal change, in this view, also entrench oppression by making remaining inequities seem inevitable and even just

Critical legal studies remains an unorthodox viewpoint in legal studies, although its methodology of using narrative to advance an argument, much criticized in the early years, has become a standard practice in the law.

By the late 1980s, the critical legal scholars were expanding their approach beyond the law, into the humanities and other social sciences, and the term critical race theory first appears in the summer of that year. From an article by Anthony E. Cook in the summer 1989 issue of the Florida Law Review:

While I will not repeat those concerns here, suffice it to say that African-American history (and the African-American critical race theory that builds upon it) illustrates the need to connect theoretical reflection on what constitutes the good life to pragmatic efforts to secure that state of existence in the real world.

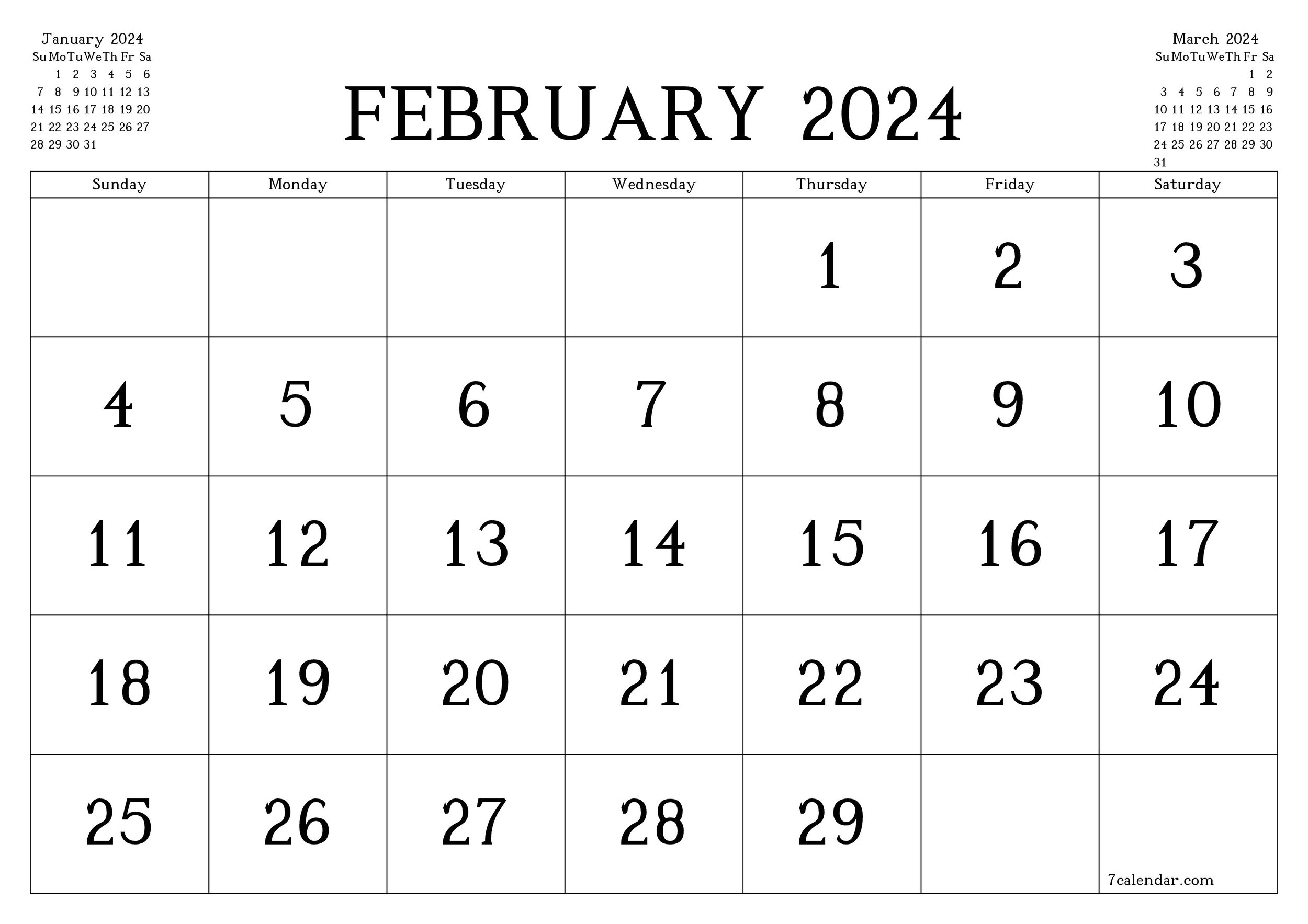

Also that summer, a conference on critical race theory was held in Madison, Wisconsin, 7–12 July 1989 that moved the scholarly movement beyond legal studies. Fred Shapiro obtained a photo of t-shirt from that Wisconsin workshop with lettering that reads:

1st

Critical Race Theory Workshop

St. Benedict Center

Madison, Wisconsin

July 7–12, 1989

So between Cook’s article and the t-shirt, the phrase critical race theory was clearly in use among scholars of that sub-field that summer, if not earlier.

Later in 1989, Randall Kennedy, a professor at Harvard Law School teaching contracts, criminal law, and the regulation of race relations, published an article arguing against the critical legal studies approach, and a 5 January 1990 article about Kennedy’s piece in the New York Times appears to be the first use of the critical race theory outside of narrow circle of CLS scholars. Richard Delgado, who is quoted in the Times piece using the term, was an attendee at the Wisconsin conference:

In the article, “Racial Critiques of Legal Academia,” Prof. Randall Kennedy of Harvard Law School sharply criticizes several prominent examples of a new approach to scholarship that is often called “critical race studies,” or “new minority scholarship.”

The new scholars take an avowedly racial or ethnic view of the law, arguing that the legal system and the nation’s elite law schools perpetuate a form of institutional racism.

[...]

In many of their works, they disregard cases and statutes, the usual fodder for law review articles. They use stories to make points on how racial issues are dealt with by society and the courts. And the stories are often intensely personal, a dramatic departure from the neutral, analytic approach of most law reviews.

[...]

Mr. [Richard] Delgado of Wisconsin [Law School], who is of Hispanic descent, said some who see the legal world as hostile to minority views have already expressed the fear that “appointment committees across the land will seize on this article and say, ‘See, even Harvard Law School has declared this new critical race theory junk,’ and use that as a way of justifying business as usual—that is, minorities won’t get hired.”

The Times piece is unusual in that it is published before the papers from the Wisconsin conference. Those started coming out in early 1990, including this one from Delgado in the Virginia Law Review of February 1990, which also shows a widening of the field beyond legal studies:

These and other scholars writing in this vein occasionally refer to themselves as the Critical Race Theory or New Race Theory group. I shall use these terms interchangeably.

Whatever label is applied to this loose coalition, its scholarship is characterized by the following themes: (1) an insistence on "naming our own reality"; (2) the belief that knowledge and ideas are powerful; (3) a readiness to question basic premises of moderate/incremental civil rights law; (4) the borrowing of insights from social science on race and racism; (5) critical examination of the myths and stories powerful groups use to justify racial subordination; (6) a more contextualized treatment of doctrine; (7) criticism of liberal legalisms; and (8) an interest in structural determinism-the ways in which legal tools and thought-structures can impede law reform

Yet another illustrative early use is in an article about the implementation of budget cuts at the City University of New York (CUNY) in the premiere issue of the Journal of Blacks in Higher Education in the fall of 1993. The article opens:

There is a mildly radical school of opinion in this country called "critical race theory." This group of black, Hispanic, and white intellectuals contends, among other things, that when liberal whites and other well-intentioned people take action to solve one of the nation's problems, the outcome will usually favor whites. The thesis holds that no matter how noble the motives and ostensibly fair and even-handed the solution, blacks will lose ground and be left with one more message that they are socially and educationally marginal and just do not belong.

And the closing paragraph of the article reads:

Clearly the decision of the CUNY trustees and the Goldstein Committee Report, upon which it is based, were not racially motivated. Yet possibly, as the critical racial theorists contend, the unequal impact on blacks is simply what happens when those who hold power make decisions that control the lives of those who don't.

That’s how critical race theory, both the term and the practice arose.

Discuss this post