19 July 2024

The element radium is a radioactive, silvery-white, alkaline-earth metal with atomic number 88 and the symbol Ra. Its most stable isotope, radium-226 has a half-life of 1,600 years. Radium is particularly toxic in that it is chemically similar to calcium and can deposit in bones, causing long-term exposure to its ionizing radiation. Once commonly used for its radioluminescent properties, because of its toxicity its only applications today are in nuclear medicine.

Radium was formed in French from rad- (from the Latin radius [ray]) +-ium (suffix used for metallic elements).

It was discovered in 1898 by the husband and wife team of Marie Sklodowska Curie and Pierre Curie, who wrote of the name:

M. Demarçay a trouvé dans le spectre une raie qui ne semble due à aucun élément connu. Cette raie, à peine visible avec le chlorure 60 fois plus actif que l'uranium, est devenue notable avec le chlorure enrichi par fractionnement jusqu'à l'activité de 900 fois l'uranium. L'intensité de cetle raie augmente donc en même temps que la radio-activité, et c'est là , pensons-nous, une raison très sérieuse pour l'attribuer à la partie radio-active de notre substance.

Les diverses raisons que nous venons d'énumérer nous portent à croire que la nouvelle substance radio-active renferme un élément nouveau , auquel nous proposons de donner le nom de radium.

(Mr. Demarçay found a line in the spectrum which does not seem to be due to any known element. This line, barely visible with chloride 60 times more active than uranium, became notable with chloride enriched by fractionation to the activity of 900 times uranium. The intensity of this line therefore increases at the same time as the radio-activity, and this is, we think, a very serious reason for attributing it to the radio-active part of our substance.

The various reasons that we have just listed lead us to believe that the new radioactive substance contains a new element, to which we propose to give the name radium.)

Sources:

Curie, Pierre and Marie Curie. “Sur une nouvelle substance radio-active, contenue dans la pechblende.” Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences, 127, December 1898, 1215–1217 at 1216–17. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Miśkowiec, Pawel. “Name Game: The Naming History of the Chemical Elements: Part 2—Turbulent Nineteenth Century.” Foundations of Chemistry, 8 December 2022. DOI: 10.1007/s10698-022-09451-w.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, June 2008, s.v. radium, n.

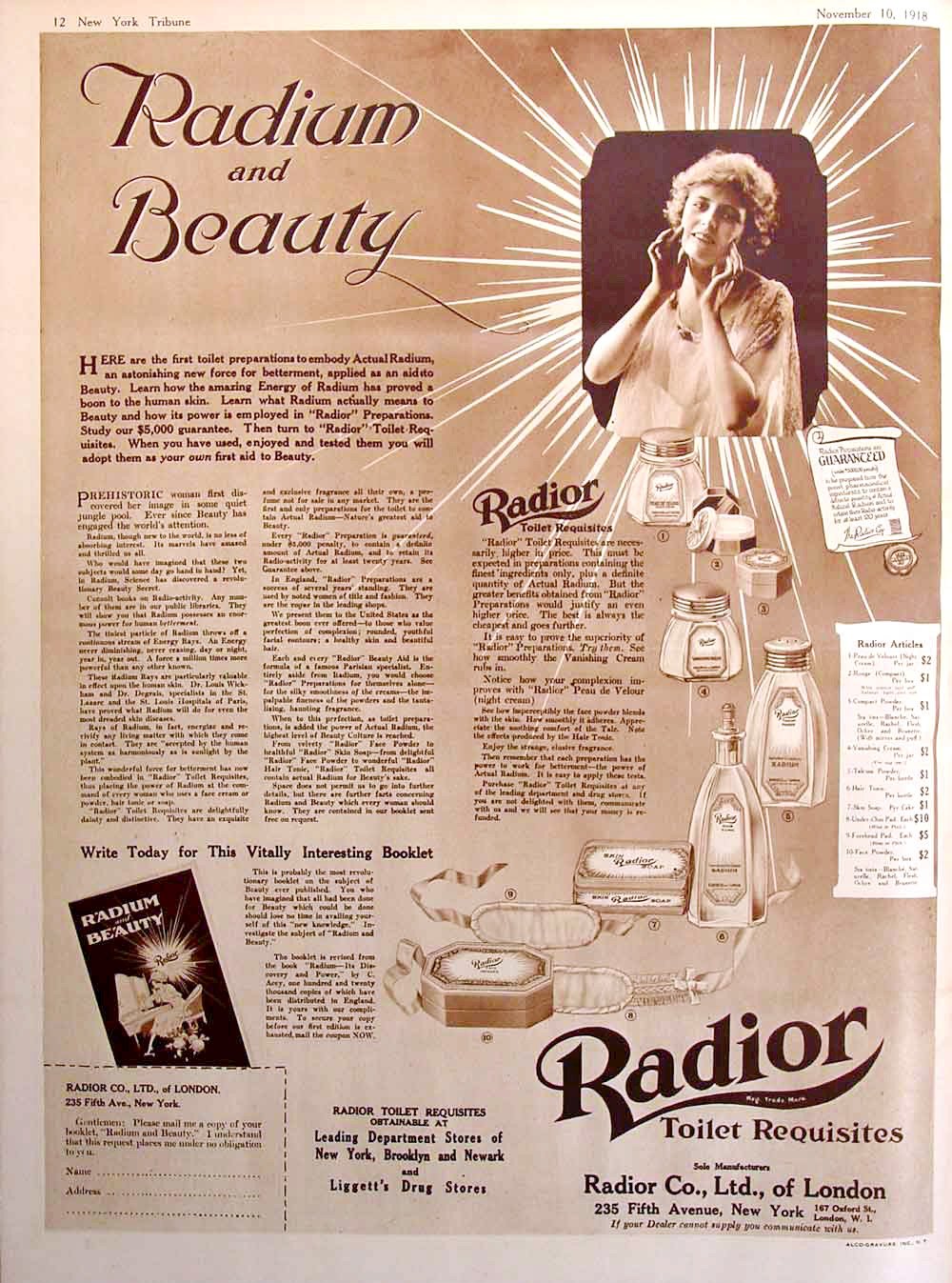

Image credit: Radior Cosmetics, 1918. New York Tribune Magazine, 10 November 1918. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain image.