1 August 2025

Cloture is the act of ending debate on a subject in a legislative assembly, and most often today it’s used in reference to the United States Senate. The word is a modern borrowing from the French clôture, which was used by the French Assembly in the nineteenth century.

We see the word being used in English to refer to the French practice as early as 1835. From London’s Morning Chronicle of 19 March of that year:

But the evident cause of stopping the debate so abruptly was the appearance of General Bugeaud at the tribune. This mad partisan, this Colonel Srathorp of the Chamber of Deputies, would infallibly have terminated a rigmarole of absurd provocation by some absurd motion in favour of Ministers, which, in consequence, most probably would have been negatived. Ministers, therefore, unable to silence General Bugeaud, were obliged to stop his mouth with the cry of “cloture;” and the Opposition, which felt that it had the best of the debate, did not show itself inclined to oppose the demand. Thus ended the interpellations.

And in the late 1840s, discussions about instituting a cloture rule, modeled on the French rule, in the House of Commons in Westminster began. As a result, when exactly the word crossed over from being used in a French context to an English one is difficult to pin down with precision. But here is an instance that is about debate in the House of Commons with no reference to the French practice in London’s The Standard of 16 May 1850, although the word is placed in italics, indicating it has not been entirely anglicized:

Everybody laments the prodigious waste of public time in the House of Commons, which results from ambitious oratory. Mr. Chisholm Anstey, Mr. Roebuck, and Mr. Urquhart are bye [sic] words among us for consuming more public time to little purpose than any three men in England. We have even had a parliamentary committee appointed to inquire into the propriety of curtailing the length of senatorial tongues, and putting the extinguisher of the cloture upon the fervid rhetoric of gentlemen like Sir Joshua Walmesley.

The inquiry into a cloture rule in Westminster continued for decades. The rule was not formally adopted until 1882. But in the mean time an informal cloture process was sometimes seen, where a member would voluntarily cease speaking when asked. Here is an example of such an informal cloture rule from the Illustrated London News of 26 February 1870:

And at last Mr. Ayrton rose to put his imprimatur on that view of the subject. While arguing generally, though the hour was a critical one, he adequately listened to; but when he seemed to be entering on an exposition of his ideas of the duty of a Chief Commissioner of Works, and was apparently about to repeat at length his disclaiming speech on his re-election for the Tower Hamlets, it is not too much to say that the small House which was existent at the moment rose with curious unanimity, ad so demanded the “cloture” that the right hon. Gentleman abruptly ceased.

And here is commentary on the cloture rule from the 1887 edition of Lester S. Cushing’s Manual of Parliamentary Practice:

In the House of Commons, England, ever since the Irish Parliamentary Party proved strong enough to combat with the Opposition by obstructing all bills in the endeavor to procure “Home Rule” for Ireland there has been nothing but turmoil over every bill proposed; to stop this the “Government Party” passed a rule which was applied wherever obstruction or debate was carried too far; this was called “Cloture.” It is used as a “gag” law, as when “Cloture” is moved every thing or motion is subordinated to the motion in favor of which “Cloture” was applied.

In the United States, the House of Representatives had always had an equivalent to the cloture rule, that is the motion to call the previous question. But in the Senate, there was no formal mechanism for ending debate. As long as a member or members held the floor, they could filibuster and forestall a vote. It wasn’t until 1917 that the Senate adopted a cloture rule requiring a two-thirds majority approval for ending debate. The number of votes was subsequently reduced to a three-fifths majority for most matters and a simple majority for certain questions, like consent for judicial nominations.

Sources:

“About Filibusters and Cloture: Historical Overview,” United States Senate, accessed 6 July 2025.

Cushing, Lester S. Manual of Parliamentary Practice: Rules of Proceeding and Debate in Deliberative Assemblies. Frances P. Sullivan, ed. New York: M. J. Ivers, 1887, §222n, 118n. HathiTrust Digital Library.

“London: Thursday, March 19, 1835.” Morning Chronicle (London), 19 March 1835, 3/4. Gale Primary Sources: British Library Newspapers.

Oxford English Dictionary Online (1891), 1989, s.v. cloture, n.

“Sketches in Parliament.” Illustrated London News. 26 February 1870, 222/1. Gale Primary Sources: The Illustrated London News Historical Archive, 1842-2003.

“Thursday Evening, May 16.” The Standard (London), 16 May 1850, 2/3. Gale Primary Sources: British Library Newspapers.

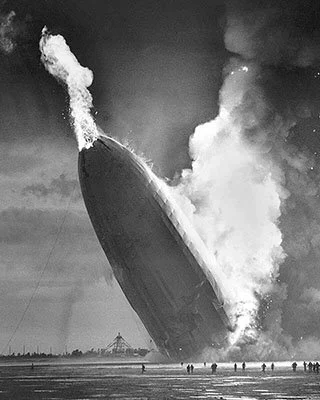

Image credit: C-SPAN, 1999. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain photo.