12 September 2025

Saved by the bell, which the OED defines as “to be rescued from a difficult situation,” comes to us, as should be no surprise, from the world of boxing. It originally and quite literally referred to a boxer who was about to be beaten into submission only to have the bell ring, signaling the end of round. The origin is so obvious that it shouldn’t merit an entry on the term, but there is an absurd-on-its-face explanation for the phrase that has currency on the interwebs that needs to be countered with evidence.

I found a non-boxing use of the phrase from 1890 that hints that the phrase was already in common use by that date, undoubtedly in boxing contexts, even if we don’t have a boxing example in print until the next year. Saved by the bell appears in an advertisement for a Toronto clothing store in The Globe on 12 December 1890. The ad, for a store named The Bell, plays on save to refer to reduced prices:

ALMOST A SMASH,

BUT SAVED BY

"THE BELL”

“The Bell” has not only saved from bankruptcy one of the largest clothing manufacturers in Canada, but it has come like a boon to the ready-made clothing buyers of Toronto. A thousand times since we opened here, just 30 days ago, have we been asked the question., How is “The Bell” able to sell the identical same goods at just one-half the price charged by the other older establishments? We give it up. Perhaps just at present we are selling at absurdly low prices, but then we bought at just such rates. TO-MORROW MORNING, AT 9.30 O’CLOCK, we continue what we believe has been the Greatest Clothing Sale ever held in Canada.

One of the regulars on this website, Richard Hershberger, turned up the oldest boxing use of the phrase that I’m aware of. It’s from the Seattle Post-Intelligencer of 30 January 1891:

ARM BROKEN IN A PRIZEFIGHT. Colored Pugilist Severely Injured in Contest at Missoula.

MISSOULA, Jan. 29.—(Special.)—A fight tonight between Ramsey, colored, and Hennessy, two pugilists of reputation in the West, from the start was hard and lively. In the fourth round Ramsey nearly knocked out Hennessey, who was very groggy, but was saved by the bell, and came up well for the fifth, in which Ramsey had the best of it. In the sixth Hennessey got in good work, and when the bell sounded for the seventh Ramsey claimed that his arm was broken. The doctor examined him and pronounced that a severe fracture had been sustained. The fight was given to Hennessey.

There are many uses of the phrase in boxing writing in the closing decade of the nineteenth century and the early ones of the twentieth.

Other than the 1890 nonce usage quoted above, the earliest non-boxing use of the phrase that I have found is still in the context of sports, in this case baseball, where the use is figurative; the “bell” is a rainstorm that ends the game and saves Yankee pitcher Waite Hoyt from ignominy after being shelled by Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics in the first two innings. It’s from the New York Times of 22 June 1928:

With the aid of old Jupe Pluve, a rugged lad with a punch in either hand, the Yankees gained a full game on the merry Mackmen of Cornelius McGullicuddy yesterday.

After a young Hank Johnson had hung a 4–0 thrashing on the eminent Robert Moss Grove in the first in the first encounter, the Athletics sallied forth and began to hit Waite Hoyt with everything but the kitchen stove. One run was in, men were on third and second with one out and the visiting firemen were a tally to the good when Jupe Pluve charged to the rescue of the hapless champions.

Old Jupe turned on a fancy brand of wet goods and Mr. Hoyt staggered gratefully to the bench when Umpire George Hildebrand suspended hostilities. After waiting a reasonable length of time the umpires called the game. Mr. Hoyt was saved by the bell.

As an aside, the quote is also notable because you don’t get many references to Jupiter Pluvius in today’s sports writing. (Jupiter Pluvius, or Jupiter Bringer of Rain, is reference to the Roman god being the god of storms.)

The earliest non-sports use of the phrase that I’ve found is from a Los Angeles Times gossip column from 31 July 1932:

Saved by the Bell Echo from Chaplin’s English tour. Whenever Charlie Chaplin and Michael Arlen meet, they have an agreement whereby each is permitted to talk about himself without interruption for five minutes by the clock. This had to be agreed upon, it appears, after the first meeting.

I did find a British, non-boxing use of saved by the bell from 1885, but it’s a literal collocation of words that is unrelated to the later American catchphrase. It’s from a piece offering commentary on a poem titled Spectre’s Bride:

The analytical notes expounding the poem and its musical setting are of so remarkable a nature that we make no excuse for quoting a few specimens of what threatens to become a new branch of literature:—“Trembling with horror and dismay [thus the librettist], From the horse the maiden fell.”—The sorry condition of the hapless girl is next related, and with the self- same breath her marvellous escape by a beneficient (sic) intervention at a supreme moment is tacked on to the phrase:—“Fainting: but in her fall she caught The rope of the lychgate bell.” With the clang of the bell the spectre knight vanishes, and Gudrun remained alone, “Saved by the bell that rang out well, saved by the holy bell.”

The absurd-on-its-face explanation mentioned above is that the phrase comes from devices rigged onto coffins so that those buried alive could ring if they woke up after having been buried. This myth is silly but pernicious and is repeated by many who should know better.

Sources:

“Arm Broken in a Prizefight.” Seattle Post-Intelligencer (Washington), 30 January 1891, 2/5. Washington Digital Newspapers.

“The Birmingham Festival.” Spectator (London), 5 September 1885, 1165/1. ProQuest Magazine.

“Display Ad 6 – No Title.” The Globe (Toronto), 12 December 1890, 5. ProQuest Newspapers.

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, accessed 12 August 2025, s.v. bell, n.1.

Harrison, James R. “Yanks Take First, Rain Stops Second.” New York Times, 22 June 1928, 16/1. ProQuest Newspapers.

Oxford English Dictionary Online, December 2012, s.v. save, v.

“Don’t Quote Me. Chatter by Tip Poff.” Los Angeles Times, 31 July 1932, B24/5. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

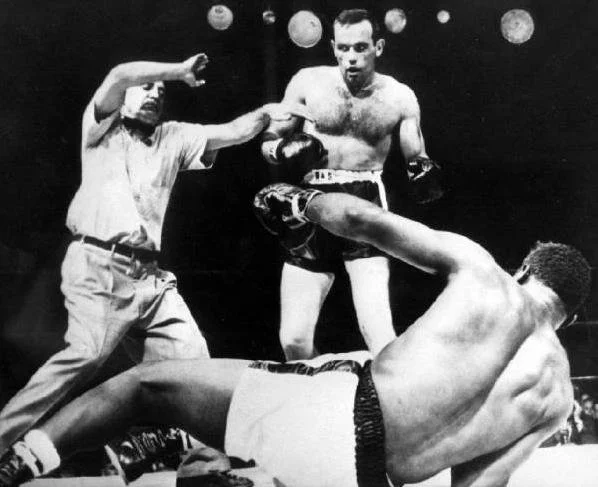

Photo credit: Unknown photographer, 26 June 1959. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain photo.