15 September 2025

That police officers often lie when giving sworn testimony has long been a truism in legal circles. Irving Younger, law professor and former Assistant US Attorney for the Southern District of New York, observed in 1967: “Every lawyer who practices in the criminal courts knows that police perjury is commonplace.” The practice was so common that it spawned its own label in police slang, testilying, a blend of testify and lying.

Testilying appears to have been coined in New York City Police Department, although it may be that the term originated elsewhere and only came to the public’s attention via use by the NYPD. It first appears in print in the New York Times on 22 April 1994:

New York City police officers often make false arrests, tamper with evidence and commit perjury on the witness stand, according to a draft report of the mayoral commission investigating police corruption.

The practice—by officers legitimately interested in clearing the streets of criminals or simply eager to inflate statistics—has at times been condoned by superiors, the report says. And it is prevalent enough in the department that it has its own nickname: “testilying.”

The Times report was picked up by the Associated Press and the term appeared in papers across the United States that same day.

Sources:

Sexton, Joe. “New York Police Often Lie Under Oath, Report Says.” New York Times, 22 April 1994, A1/1. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Younger, Irving. “The Perjury Routine.” The Nation, 8 May 1967, 596–97 at 596/1. EBSCOhost The Nation Archive.

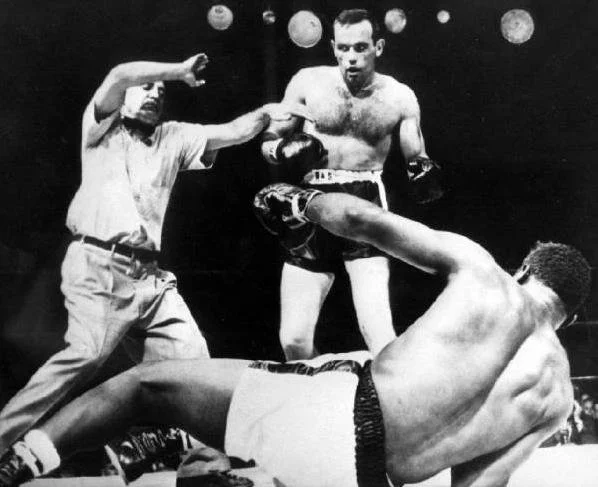

Photo credit: Nick Ut/Associated Press, 1995. Fair use of a low-resolution copy of a copyrighted image used to illustrate the topic under discussion.