4 October 2021

A rule of thumb is any method of estimation or practice that is based on practical experience and that will work sufficiently well in a majority of, but by no means all, cases. There is a widespread belief that the phrase rule of thumb has its origins in an old legal doctrine that says a husband has the right to beat his wife so long as the weapon used is no thicker than a person’s thumb. Such a belief, to use the coinage of Henry Ansgar Kelly, is folklaw. But it is folklaw with a kernel of truth within it, and dividing the truth from fiction in this case must be carefully done.

First, the phrase rule of thumb does not have its origins in any such legal doctrine, real or imagined.

Second, there was an old legal doctrine that a husband could beat his wife, so long as the beating was not too severe. But this doctrine was repudiated much earlier than many people think, by the seventeenth century in England, and for the most part the doctrine was never recognized in the United States.

Third, there never was any legal doctrine regarding the size of the weapon used in such a beating, but on rare occasion some judges did refer to such a supposed doctrine in their judicial opinions.

Fourth, and most importantly, spousal abuse was and remains a significant problem, and the courts and law enforcement have all too often looked the other way when men have beaten their wives. The fact that no such folklaw doctrine has ever actually existed in no way diminishes this reality, and it should not be used to downplay the problem of spousal abuse.

Let’s take on the origin of the phrase first and then discuss the history of the supposed legal doctrine.

The word thumb itself, the word for the thick, inner digit of the human hand, comes from the Old English þuma, which in turn is from a common Proto-Germanic root. The use of thumbs as a unit of measure stems from the fact that the distance between the tip of a person’s thumb and the first knuckle is more or less one inch in length, and the thumb can, therefore, be used to give a rough estimate of an object’s length. Use of the thumb as a unit of measure dates to at least to the turn of the fifteenth century, when, in setting out standards of measurement, the statutes of Robert III of Scotland (reigned 1390–1406) included the following law, which uses the Latin pollex (thumb) as a name for a unit of measure:

Pollices mensuratos cum Pollicibus trium hominum, cum videlicet ex magno, mediocri et parvo, et secundum mediocrem Pollicem debet stare, aut secundum longitudinem trium granorum hordei sine caudis.

(Thumbs are to be measured by the thumbs of three men, namely one large, one medium, and one small, and should stand in accordance with the medium thumb, or in accordance with the length of three grains of barley without tails.)

English language mention of a thumb as a unit of measure appeared in Randle Cotgrave’s 1611 French-English dictionary:

Poulcée: f. an inch, or inch-measure; the breadth of a thumbe.

And thumb appears as a synonym for inch in Gerard Maynes 1622 guide to mercantile customs, Consuetudo, vel Lex mercatoria, or The Ancient Law-Merchant:

A Thumbe or Inch is 6 Graines or Barley cornes, making two of them three.

The phrase rule of thumb is an extension of this use in measurement and appears to have originated in Scotland, as all of the earliest citations of its use are by Scottish writers, and one early use claims the phrase is part of an old Scottish proverb.

The earliest known use of the phrase rule of thumb is in a theological tract by James Durham. The date is uncertain, but it must have been written before his death in 1658. The metaphor is clearly one of measurement:

It is to be feared, that many others are but building castles in the air, castles of come down when the rain shall descend, the winds blow, and the floods beat, having much more shew then substance, and solid work; and the way to make it sicker, sure and solid work, that will abide the tryal, is to lay it to the Rule, and to try it thereby; many profest Christians are like to foolish builders, who build by guess, and by rule of thumb, (as we use to speak) and not by Square and Rule

In 1680, John Alexander wrote this in an anti-Quaker tract:

For first, That must be the Rule of Faith and Manners by which every matter of Faith and Manners ought to be examin'd seeing every thing that is examined must be examined by its Rule, or else it will be done by Guess and Rule of Thumb, as the Jest is. But every matter of Faith and Manners ought to be examined by the Scriptures

William Hope, another Scotsman, used it in his 1691 The Compleat Fencing-Master:

The Judging of Distance exactly is one of the hardest things to be acquired in all the Art of the smal-Sword; and when once it is acquired it is one of the usefulest things, and sheweth a Mans Art as much as any Lesson in it; but I am for no Mans Retiring too much, unless upon a very good Design, and that hardly any Ignorant of this Art can have, because what he doth (as the common Proverb is) he doth by rule of Thumb, and not by Art.

And James Kelly recorded the following Scottish proverb “explained and made intelligible to the English reader” in a 1721 collection of such aphorisms:

No Rule so good as Rule of Thumb, if it hit.

But it seldom hits! Spoken when a Thing falls out to be right which we did at a Venture.

In addition to all of these early uses being Scottish, they all used rule of thumb as a metaphor for measuring length, and all highlighted its uses as being inaccurate and, in the case of swordplay at least, potentially fatal.

As to the veracity of the claims about the law, it is indeed the case English common law did once allow a husband to hit his wife, so long as the beating wasn’t too severe. But there was never any rule about thumb-sized sticks. William Blackstone, in his 1766 Commentaries on the Laws of England refers to this legal doctrine, but says it was abandoned by the reign of Charles II (1660–85), although many of the common folk believed it still to be valid law:

The husband also (by the old law) might give his wife moderate correction. For, as he is to answer for her misbehaviour, the law thought it reasonable to intrust him with this power of restraining her, by domestic chastisement, in the same moderation that a man is allowed to correct his servants or children; for whom the master or parent is also liable in some cases to answer. But this power of correction was confined within reasonable bounds; and the husband was prohibited to use any violence to his wife, aliter quam ad virum [i.e., differently than to a man], ex causa regiminis et castigationis uxoris suae [for the sake of the government and chastisement of his wife], licite et rationabiliter pertinet [as is legally and rationally suitable]. The civil law gave the husband the same, or a larger, authority over his wife; allowing him, for some misdemeanors, flagellis et fustibus acriter verberare uxorem [to beat his wife vigorously with whips and sticks]; for others, only modicam castigationem adhibere [to employ moderate punishment]. But, with us, in the politer reign of Charles the second, this power of correction began to be doubted, and a wife may now have security of the peace against her husband; or, in return, a husband against his wife. Yet the lower rank of people, who were always fond of the old common law, still claim and exert their antient privilege, and the courts of law will still permit a husband to restrain a wife of her liberty, in the case of any gross misbehavior.

Note that Blackstone makes no mention of thumbs or even the size of any such whips and sticks. And note that Blackstone acknowledges that spousal abuse is not always the case of a husband beating the wife. Sometimes the husband is the victim.

The origin of the stick-no-bigger-than-a-thumb folklaw would seem to be a 1782 incident, or at least that’s the earliest such connection between thumbs and weapons of spousal assault that has been found. The incident involved Francis Buller, a judge on the king’s bench who allegedly stated that it was lawful for a husband to beat his wife with stick so long as it was no bigger than his thumb. No record of Buller saying any such thing has been found, but it was widely attributed to him at the time and earned him the sobriquet of Judge Thumb. The lack of a written record indicates, that if he said such a thing, it may have been a personal opinion and not any kind of judicial ruling.

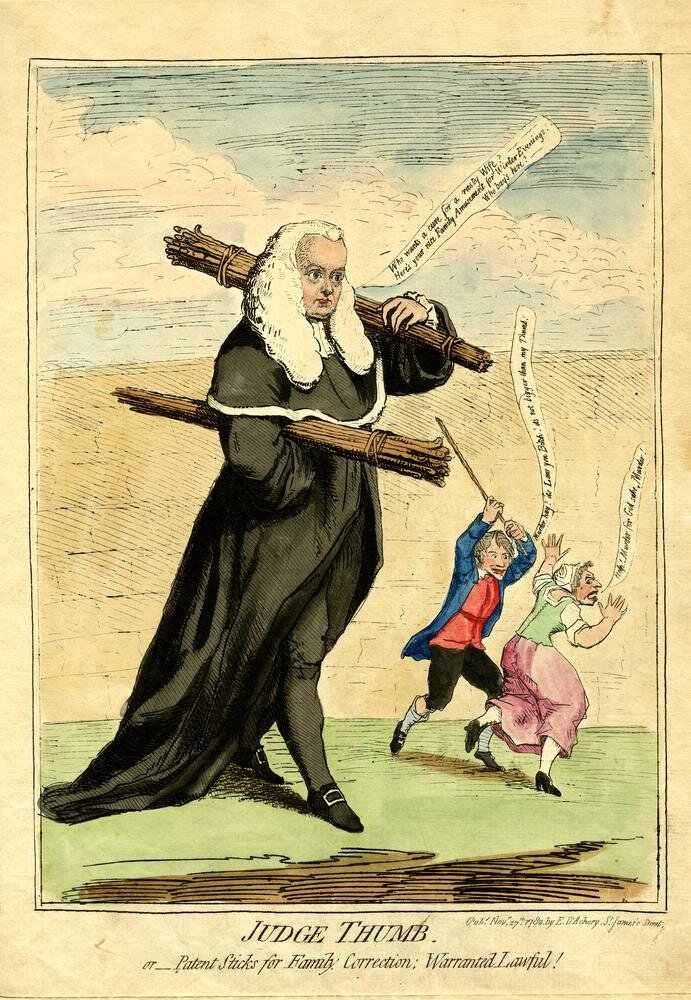

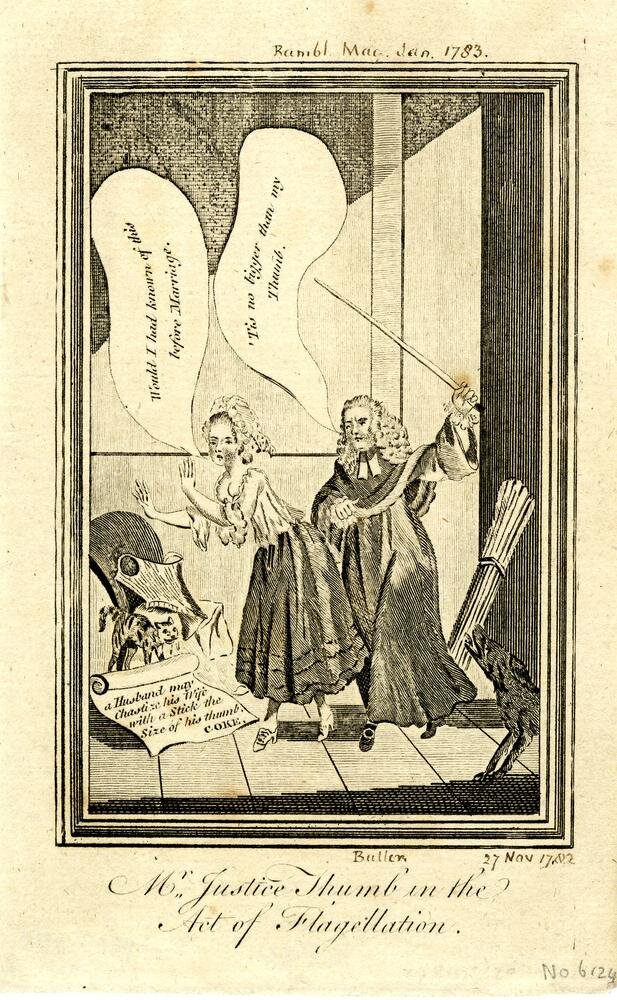

Important in understanding this incident is that public opinion at the time was solidly against Buller’s statement, and he was roundly excoriated for it. Spousal abuse in eighteenth-century England, while then all too common as it unfortunately still is today, was uniformly seen as wrong, at least by the press and those that had a public voice. Two satirical cartoons about Buller and his unfortunate statement were published that year, both pictured here. One is by James Gillray, titled Judge Thumb, or__Patent Sticks for Family Correction: Warranted Lawful! and published on 27 November 1782. The second is anonymous, titled Mr. Justice Thumb in the Act of Flagellation and is of uncertain date. The copy in the British Museum bears two dates, one says “Rambl. Mag. Jan. 1783” and the other 27 November 1782. Complicating matters, the British Museum’s description of the article gives a date of 1 February 1782. I have been unable to locate the Rambler Magazine in question.

Nor was the incident quickly forgotten. A poem submitted to the Wit’s Magazine of October 1784 reads:

Yet still, if to wed proves at last my sad lot,

Thro’ Fate’s never-failing decree;

I’ll endeavour to tie up the conjugal knot,

With a girl who’s good-temper’d and free.But should she, by brawling, embitter my life

Judge Thumb gives the law on my side;

Who says, if a man has a termagant wife,

With a CANE he may liquor her hide.

And a song titled The Prophets appears in a 1790 collection of popular tunes:

Then Moses sung first as a president should,

And laid down the law as at time it stood;

He quoted his thumb-book, and swore with

a nod, [with a rod.

That the ladies should soon flog Judge Thumb

Derry down.

It is this alleged statement by Buller that first promulgated the folklaw. The folklaw has been mentioned in a handful of subsequent legal decisions, all American. In only one decision did a court recognize the folklaw as valid, but that was reversed on appeal. But while the idea that a man could whip his wife with a thumb-sized cane or switch was almost always rejected by American courts, these nineteenth-century decisions are hardly great victories for the rights of women.

The first is a Mississippi case from 1824, Bradley vs. State, in which the judge opined:

It is true, according to the old law, the husband might give his wife moderate correction, because he is answerable for her misbehaviour; hence it was thought reasonable, to intr[u]st him, with a power, necessary to restrain the indiscretions of one, for whose conduct he was to be made responsible. [...] Sir William Blackstone says, during the reign of Charles the first, this power was much doubted.—Notwithstanding the lower orders of people still claimed and exercised it as an inherent privilege, which could not be abandoned, without entrenching upon their rightful authority, known and acknowledged from the earliest periods of the common law, down to the present day. I believe it was in a case before Mr. Justice Raymond, when the same doctrine was recognised, with proper limitations and restrictions, well suited to the condition and feelings of those, who might think proper to use a whip or rattan, no bigger than my thumb, in order to inforce the salutary restraints of domestic discipline.

While the judge declared the husband’s actions to be “deplorable,” he ruled that the courts should not interfere in cases of “moderate chastisement,” such matters being better dealt with by the family. The “Justice Raymond” the Mississippi judge referred to is probably Lord Robert Raymond, a British judge who served from 1724-33. But no one has been able to find a ruling by Raymond on spousal abuse. The Mississippi judge probably confused Raymond with Buller.

A pair of cases from North Carolina occur later in the nineteenth century. In the 1868 matter of State v. Rhodes, a state trial court had found:

that the defendant struck Elizabeth Rhodes, his wife, three licks, with a switch about the size of one of his fingers (but not as large as a man's thumb) without any provocation except some words uttered by her and not recollected by the witness.

But because the switch was smaller than a man’s thumb, the court acquitted the husband. On appeal, the North Carolina Supreme Court argued:

Two boys under fourteen years of age fight upon the play-ground, and yet the courts will take no notice of it, not for the reason that boys have the right to fight, but because the interests of society require that they should be left to the more appropriate discipline of the school room and of home. It is not true that boys have a right to fight; nor is it true that a husband has a right to whip his wife. And if he had, it is not easily seen how the thumb is the standard of size for the instrument which he may use, as some of the old authorities have said; and in deference to which was his Honor's charge. A light blow, or many light blows, with a stick larger than the thumb, might produce no injury; but a switch half the size might be so used as to produce death. The standard is the effect produced, and not the manner of producing it, or the instrument used.

And the state supreme court ruled that while a husband beating his wife in any manner was illegal, courts should take no notice:

unless some permanent injury be inflicted, or there be an excess of violence, or such a degree of cruelty as shows that it is inflicted to gratify his own bad passions.

So, the North Carolina Supreme Court ruled that the lower court had erred in finding the man not guilty because of the size of the switch, but said he was still not guilty because no permanent injury was inflicted. But in so doing, the court also acknowledged that it was out of step with contemporary legal opinion, as laws in other states and prevailing legal thought would disagree with its decision:

Because our opinion is not in unison with the decisions of some of the sister States, or with the philosophy of some very respectable law writers, and could not be in unison with all, because of their contrariety— decent respect for the opinions of others has induced us to be very full in stating the reasons for our conclusion.

This 1868 decision was subsequently overturned as “obsolete or repugnant to the freedom and independence of this state and our form of government” and is no longer a valid decision under North Carolina law.

A few years later, in the 1874 case of State v. Oliver, the North Carolina Supreme Court reaffirmed its earlier ruling, while upholding the conviction of a man because his beating his wife, while inflicting no permanent injury, was done out of “malice and cruelty”:

We may assume that the old doctrine, that a husband had a right to whip his wife, provided he used a switch no larger than his thumb, is not law in North Carolina. Indeed, the Courts have advanced from that barbarism until they have reached the position, that the husband has no right to chastise his wife, under any circumstances.

But from motives of public policy,--in order to preserve the sanctity of the domestic circle, the Courts will not listen to trivial complaints.

If no permanent injury has been inflicted, nor malice, cruelty nor dangerous violence shown by the husband, it is better to draw the curtain, shut out the public gaze, and leave the parties to forget and forgive.

No general rule can be applied, but each case must depend upon the circumstances surrounding it.

In the 1871 case of Fulgham v. The State, Alabama did better than these other states. It ruled that any instance of a person hitting their spouse, other than in self-defense, is a crime. In the case, the husband was convicted of striking his wife after she rebuked him. The trial court rejected the defendant’s argument that moderate chastisement was permissible and specifically said the prior rulings in Mississippi and North Carolina were not the law in Alabama. On appeal, the state supreme court affirmed the lower court’s ruling, letting the conviction stand. In its ruling, the state supreme court didn’t mention thumbs, but it did refer to “rod which may be drawn through a wedding ring” as not being a valid standard:

Since [Blackstone’s time], however, learning, with its humanizing influences, has made great progress, and morals and religion have made some progress with it. Therefore, a rod which may be drawn through the wedding ring is not now deemed necessary to teach the wife her duty and subjection to the husband. The husband is therefore not justified or allowed by law to use such a weapon, or any other, for her moderate correction.

In its conclusion, the Alabama Supreme Court called spousal abuse, “a low and barbarous custom, and never was a law.”

So, to sum up the jurisprudence on the question of beating one’s wife with a weapon smaller than a man’s thumb, what we have is that standard was never valid in England, and the idea that a husband could use moderate corporal punishment on his wife has been rejected since at least the seventeenth century. One eighteenth-century English judge, i.e., Buller, probably made some sort of statement to the effect that it was permissible to do so, but he was roundly excoriated for saying it. In the United States, courts generally ruled that spousal abuse was wrong, but some opined that except in severe cases it was not a judicial matter. One lower court did rule that the thumb rule was valid, but it was overturned on appeal. And while a handful of states in the nineteenth century did rule that moderate corporal punishment was if not strictly legal, not a matter for the courts to adjudicate, these were the exception. None of these legal cases invoked the phrase rule of thumb.

The association of the phrase rule of thumb with the folklaw began in the 1970s. A pair of writings on spousal abuse seem to have made that connection. In 1976, feminist activist Del Martin wrote the following in her book Battered Wives, which has been misinterpreted by many:

In America, early settlers held European attitudes towards women. Our law, based upon the old English common-law doctrines, explicitly permitted wife-beating for correctional purposes. However, certain restrictions did exist, and the general trend in the young states was toward declaring wife-beating illegal. For instance, the common-law doctrine had been modified to allow the husband “the right to whip his wife, provided that he used a switch no bigger than his thumb”—a rule of thumb, so to speak.

Martin’s summary of the common and case law is incorrect—although the fact that the legal establishment frequently ignored cases of spousal abuse certainly was the case—but her use of rule of thumb is not a claim that the phrase came out of the practice. Her use of “so to speak” indicates that she is saying that the any doctrine of moderate punishment was a sort of rough and ready rule to excuse behavior that should be inexcusable. But the passage can be and was misread.

A year after Martin’s book was published, Terry Davidson wrote the following:

One of the reasons nineteenth century British wives were dealt with so harshly by their husbands and by their legal system was the “rule of thumb.” Included in the British Common Law was a section regulating wifebeating. The law was created as an example of compassionate reform when it modified the weapons a husband could legally use in “chastising” his wife. The old law had authorized a husband to “chastise his wife with any reasonable instrument.” The new law stipulated that the reasonable instrument be only “a rod not thicker than his thumb.” In other words, wifebeating was legal.

As we have seen, other than the fact that spousal abuse was and is all too prevalent, nothing in this paragraph is correct. Elsewhere in the piece Davidson quotes Blackstone, but interprets Blackstone’s statement of the old practice as an endorsement.

Given the proximity of the dates of publication, it seems unlikely that Davidson was aware of Martin’s book when she wrote her article. But the two in tandem seem to have been enough to implant the false idea in the public’s consciousness.

To sum up: yes, spousal abuse is an evil and all too prevalent; no, the phrase rule of thumb does not have its origins in a legal justification for spousal abuse.

Sources:

Alexander, John. Jesuitico-Quakerism Examined, or, a Confutation of the Blasphemous and Unreasonable Principles of the Quakers. London: Dorman Newman, 1680, 23. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Blackstone, William. Commentaries on the Laws of England, vol. 1. Dublin: John Exshaw, et al., 1766, 432–33. Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO).

Bradley vs. State, Supreme Court of Mississippi, 1 December 1824, 1.Morr.St.Cas. 20, Walker 156, 1 Miss. 156, 1824 WL 631. Thomson Reuters: Westlaw.

Calvert, Robert. “Criminal and Civil Liability in Husband-Wife Assaults.” In Suzanne K. Steinmetz and Murray A. Straus, eds. Violence in the Family. New York: Dodd Mead, 1975, 88–91. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Cotgrave, Randle. A Dictionarie of the French and English Tongues. London: Adam Islip, 1611, s.v. poulcée. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Davidson, Terry. “WifeBeating: A Recurring Phenomenon Throughout History.” In Maria Roy, ed. Battered Women: A Psychosociological Study of Domestic Violence. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1977, 18–19. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Du Cange, Carolo du Fresne. Glossarium mediae et infimae Latinitatis. Paris: 1883–87, s.v. pollex. Brepolis: Database of Latin Dictionaries.

Durham, James. Heaven Upon Earth (before 1658). Edinburgh: Heir of Andrew Anderson, 1685, 217. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Fulgham v. The State, Supreme Court of Alabama, 1 June 1871, 46 Ala. 143, 1871 WL 1013. Thomson Reuters: Westlaw.

Hope, William. The Compleat Fencing-Master. London: Dorman Newman, 1691, 157. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Kelly, Henry Ansgar. “‘Rule of Thumb’ and the Folklaw of the Husband’s Stick.” Journal of Legal Education, 44.3, September 1994, 341–365. JSTOR.

Kelly, James. A Complete Collection of Scotish Proverbs Explained and Made Intelligible to the English Reader. London: William and John Innys and John Osborn, 1721, 257. Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO).

Malynes, Gerard. Consuetudo, vel Lex mercatoria, or The Ancient Law-Merchant. London: Adam Islip, 1622, 52. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Martin, Del. Battered Wives (1976), revised, updated. San Francisco: Volcano Press, 1981, 31. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, March 2011, modified September 2019, s.v. rule of thumb, n. and adj.

“The Prophets.” The Modern Syren, A Collection of the Most Celebrated New Songs. Newcastle: S. Hodgson, 1790. 180. Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO).

State v. Oliver, Supreme Court of North Carolina, 1 January 1874, 70 N.C. 60, 1874 WL 2346. Thomson Reuters: Westlaw.

State v. Rhodes, Supreme Court of North Carolina, 1 January 1868, Phil.Law 453, 61 N.C. 453, 1868 WL 1278, 98 Am.Dec. 78. Thomson Reuters: Westlaw.

Stone, W. “Select Answers to the Prize Enigma.” The Wit’s Magazine (October 1784), vol. 2. London: Harrison, 1785. 399. Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO).

Virmani v. Presbyterian Health Services Corp., Supreme Court of North Carolina, 25 June 1999, 350 N.C. 449, 515 S.E.2d 675, 27 Media L. Rep. 2537. Thomson Reuters: Westlaw.

Image credit: James Gillray, “Judge Thumb,” 27 November 1782. The British Museum. Public domain image as a mechanical reproduction of a work that is in the public domain.