31 August 2021

Wop is an American ethnic slur for an Italian person, and sometimes more generally for someone from southern Europe or even any foreigner. It starts appearing in American speech in the early years of the twentieth century.

It can, with a fair degree of confidence, be traced back to the Latin vappa, a noun literally referring to spoiled wine and figuratively to a worthless person, a good-for nothing. We can see this second, figurative sense in the poetry of Catullus (c.84–c.54 BCE):

Verani optime tuque mi Fabulle,

quid rerum geritis? satisne cum isto

vappa frigoraque et famem tulistis?(Most excellent Veranius, and you my Fabullus, how are you? Have you borne cold and hunger with that good-for-nothing [Piso] long enough?)

Horace (65–8 BCE) also uses this sense in his first satire, but he used it in a more specific sense of a spendthrift:

non ego, avarum cum veto te fieri, vappam iubeo ac nebulonem

(When I forbid you from being a miser, I am not asking you a be a spendthrift and prodigal.)

This sense was continued in the Romance languages, and in Spanish guapo came to mean a dandy, a well-dressed man, a metrosexual. This sense transferred to the Sicilian dialect during Spanish rule of that island from the late thirteenth to the early eighteenth centuries, where it also acquired the connotation of arrogance and bluster. Immigrants from Sicily brought the word to North America at the turn of the twentieth century, where it was often used to refer to work bosses and eventually to workers and laborers themselves. It slipped into English usage with the senses we know today. Unsurprisingly, the American uses start in New York City and spread from there over the next few years.

The earliest appearances of wop in American slang that have been found were unearthed by Douglas Wilson. Earlier examples probably exist, but searching for wop in databases of digitized texts is very difficult due to the large number of OCR errors with such a short word. It appears in the New York Sun of 16 February 1906 as the nickname for a juvenile delinquent:

Detective J.J. McVea of the Charles street station, who arrested the boys, says that the robbery of the safe was a remarkable one and showed no trace of amateurism. It was committed by four boys. Besides Lyons and Murphy, he says, there were in it Albert Moquin, 14 years old, of 68 West Third street, and one whom Lyons calls “Oscar the Wop,” or “Oscar the Dago.”

The Sun also records this use on 18 November 1906, this one clearly in the sense of someone of Italian, specifically Sicilian, descent:

There was a time, not very long ago, when you couldn't find a Wop—that means an Italian in the latest downtown dialect—in Danny's resort even by using a microscope. But to-day it's different. The members of the Five Points gang, all dark skinned sons of Sicily, grew tired of flitting from place to place, with no set rendezvous for their nightly gatherings. A number of the Pointers used to frequent the place, and it wasn't long before the entire gang became regulars.

The next year the Evening World, another New York paper, has this usage that equates the term with low social class, but not necessarily being of Italian descent. From the 13 April 1907 issue:

There’s plenty of peasants these days, kids. Only we call them muckers and wops. They haven’t any clean clothes, or if they have they won’t wear them, and they don’t care whose wedding day it is.

Several months later, the same paper refers to an Italian-American boxer as a wop (and a Jewish boxer as being from the Ghetto), from the Evening World of 25 June 1907:

At the Brown A. A., on West Twenty-third street, Joe Bernstein, the champion of the Ghetto, will tackle Frankie Paul, the Wop champion, in a six-round go.

And in the Sun of 26 August 1907, we get this account of a dog vs. cat fight escalating into street fighting between ethnic gangs:

The armed truce which had bridged hostilities between the Oak street Wops and the Madison street Yids for a whole week was broken rudely yesterday afternoon when the Giannini Kid’s yellow dog chased the Moe Lichtenstein family cat into the line of sewer pipes stretched ready for laying along James street just below Madison and there slew her. Bloody war flamed along James street on the instant and the blood of the Lichtenstein cat was not avenged.

Green’s Dictionary of Slang records a use of black wop by cartoonist Theodore A. “TAD” Dorgan from 1907. I have been unable to locate the original source, so the context of the short quotation in that dictionary is a bit vague, it may refer to a dark-complexioned person of Italian descent rather than an African American, but I cannot be sure without seeing the original:

I’d bet two bits on that black wop if I wasn’t saving up for a new hat.

The next year it appears outside of New York, but it is in a syndicated story originating from New York. This version was published in the Cincinnati Enquirer on 25 April 1908. Here it is being used in the sense of a well-dressed, important man, specifically a well-respected racing tout, but who by his name would appear to be Irish:

Mooney strolled aft and was soon remarked. “Who’s the wop in the Hi Henry’s?” asked a semi-occasional of young Miffitt, the boy with the proud papa.

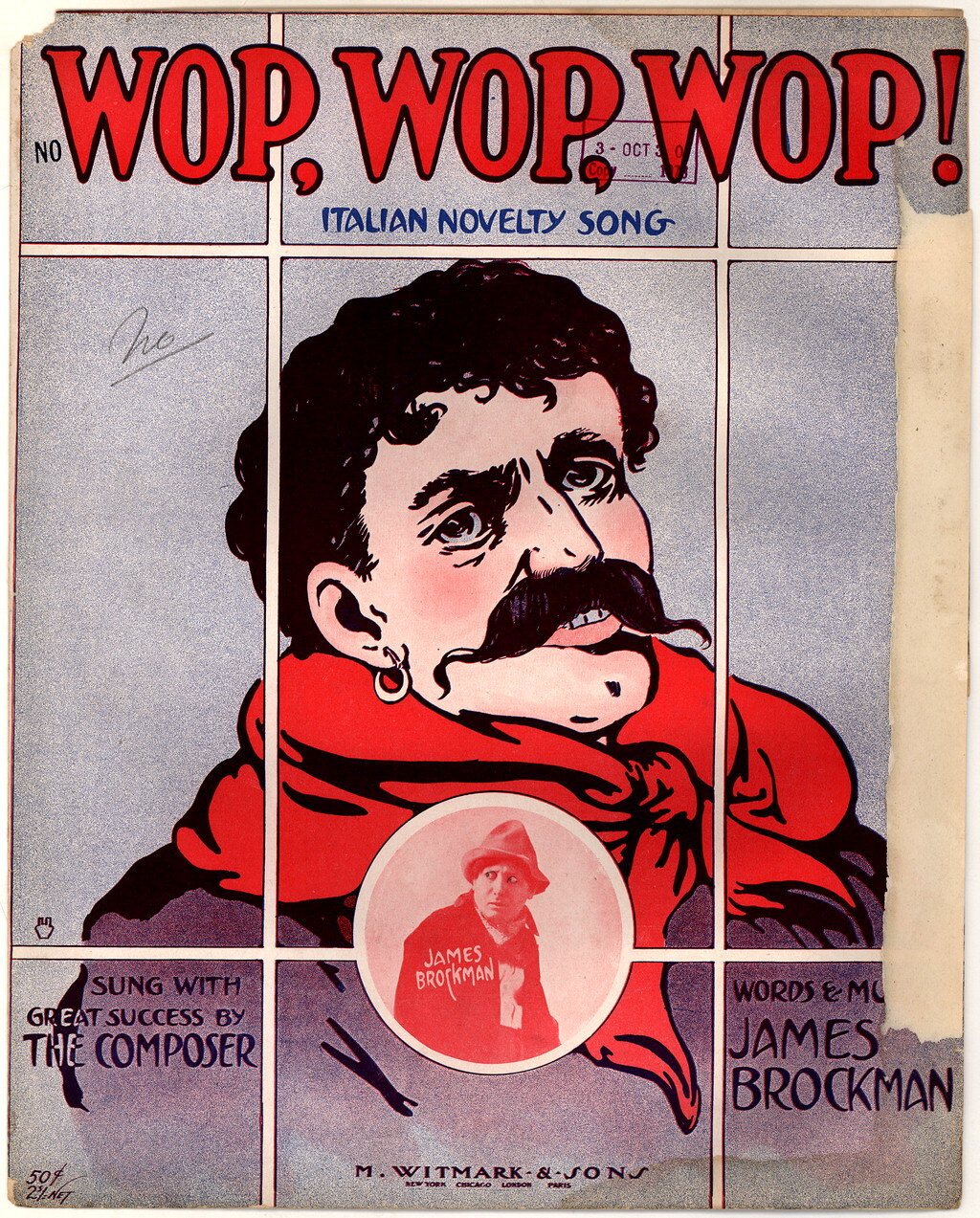

Also in 1908, an “Italian novelty” song called Wop, Wop, Wop! by James Brockman was released. The song is quite offensive, but it’s linguistically interesting in that it notes that the term wop is relatively new and because the song’s theme is the changing nature of ethnic slurs. The first verse and chorus go:

When first I come to dees acountiree,

All people call me dago man;—

And you can bet dot was no fun to me,

I feel joust like the empty banan.

Den dey change and call me Guinie

Twice as bad-a name dey gimmie,

I say please make a drop, I beg-a dem to stop,

Now dey call me Wop!Wop, Wop, Wop!

I wonder why dey call-a me Wop!

It’s a one-a big-a shame,

Dey call me nick-a name,

Dey shout a Toney, you’re a phoney

Look-a like-a Macaroni;

Wop! Wop! Wop!

I wish a cop would make-a dem stop,

First dey call-a me a Dago,

den Guinie, Guinie, Guinie!

Now it’s Wop! Wop! Wop! Wop!

A little later that year, we see wop being used to mean an Italian man. Here it is in a Canadian paper, but it is reporting from New York. From the account of a marathon held at Madison Square Garden published in the Montreal Gazette of 17 December 1908:

The biggest crowd ever seen in Madison Square Garden witnessed the race. At no time in the history of the famous amusement resort has such a closely packed audience been jammed within its four walls. At one time during the closing hours of the recent six-day bicycle race there was a gathering that held the palm for numbers up that time, but this showing was outdone last night when Floyd MacFarland fired the shot at 9.14 that started the Indian and the Wop on their journey of twenty-six miles and 380 yards.

But by 1909 we start seeing unambiguous uses of wop from outside of New York. From the Charleston, South Carolina Sunday News of 14 March 1909, a use as a nickname for a boxer:

I know a duck that’s got two ringside seats that he wants to get rid of because he can’t go himself, and he’ll peddle ’em for less than they cost him. Rattling go, at that. Between Young Corbett, that’s come back, you know, and Marto, the Wop. How ’bout? Some good prelims, and that good main scrap. Sound good?

That same day, another syndicated piece, apparently by the same writer as the story about the racing tout—there is no byline, but the some of the characters in the story are the same—is published in the Washington Post:

Lally looked at him hard, and the tough arm muscles under his shirt sleeves swelled up. “Look here, you pig-eyed selling plater!” he said hotly. “Do you see this Wop?” indicating Frank. “Well if you don’t beat it in a pair of seconds I’ll take this Wop and hit you over the head with him.”

The ethnicity of the man in question is not given.

That’s how wop went from Latin for a good-for-nothing person to American slang for a person of Italian descent.

The idea that wop is an acronym for without passport or without papers has no evidentiary basis at all. This spurious explanation dates to the 1970s.

Sources:

“Battle of the Sewer Pipes.” The Sun (New York), 26 August 1907, 5. Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

“Boxing Stags To-Night.” Evening World (New York), 25 June 1907, 12. Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

“Boy Safe Looters.” The Sun (New York), 16 February 1906, 3. Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

Brockman, James, composer. “Wop, Wop, Wop!” (song). New York: M. Witmark and Sons, 1908. Library of Congress: Historic Sheet Music Collection, 1800–1922.

Catullus. Poem 28. Catullus, Tibullus, Pervigilium Veneris, second edition with corrections. G.P. Goold, ed. F.W. Cornish, trans. Loeb Classical Library 6. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2017, lines 3–5, 32.

“Danny’s Music All On Strike.” The Sun (New York), 18 November 1906, 16. Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, 2021, s.v. wop, n.1.

Horace. “Satire 1.1.” Horace: Satires, Epistles, the Art of Poetry, revised edition. H.R. Fairclough, trans. Loeb Classical Library 194. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1929, lines 103–04, 12.

“Keats’s Fate Made Him Sad” (12 March 1909). Sunday News (Charleston, South Carolina), 14 March 1909. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Lewis, Charlton T. and Charles Short. A Latin Dictionary, Oxford: Oxford UP, 1879, s.v. vappa.

McCardell, Roy L. “The Chorus Girl.” Evening World’s Daily Magazine (New York), 13 April 1907, 8. Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

“Mr. Granaday Seeks Revenge” (syndicated). Washington Post, 14 March 1909, M3. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. wop, n.2. and adj.

“Tout Had an Easy Mark” (syndicated). Cincinnati Enquirer (Ohio), 25 April 1908, 13. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

“Will Race Shrubb.” Gazette (Montreal), 17 December 1908, 2. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Wilson, Douglas G. “‘Wop’ in 1908?” ADS-L, 29 April 2010.

Zimmer, Ben. “‘Wop’ Doesn’t Mean What Andrew Cuomo Thinks It Means.” The Atlantic, 23 April 2018.

Image credit: Brockman, James, composer. “Wop, Wop, Wop!” (song). New York: M. Witmark and Sons, 1908. Library of Congress: Historic Sheet Music Collection, 1800–1922. Public domain image.