12 November 2021

[13 November 2021: added reference to the French text of Mandeville. 15 November 2021: added reference to Latini.]

Crocodile tears are an insincere display of sadness or compassion. The phrase comes from the false belief that crocodiles either shed tears in mourning for their victims or that they use tears to lure prey to them. This belief appears in the medieval period but probably dates back into antiquity, although the phrase crocodile tears is more recent. While by no means restricted to women, over the centuries the idea of crocodile tears has often been used misogynistically to brand women as using feigned emotions to deceive men.

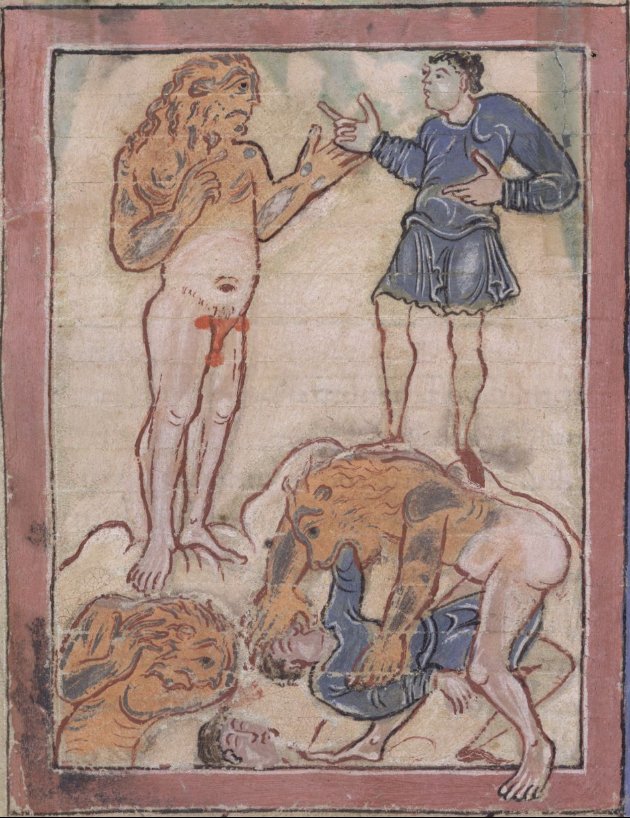

The notion of a creature shedding tears for its prey dates to at least the turn of the eleventh century when it appears in De rebus in Oriente miribilibus (The Wonders of the East). The anecdote appears in two manuscripts. One, British Library, Cotton MS Tiberius B.v., contains the story in both Anglo-Latin and Old English. The second is the Beowulf manuscript, British Library, Cotton MS Vitellius A.xv., where a slightly older Old English version appears. From Tiberius B.v.:

Itaque insula est in rubro mari in qua hominum genus est quod apud nos appellatur donestre, quasi divine a capite usque: ad umbilicum, quasi homines reliquo corpore similitudine humana, nationum omnium linguis loquentes cum alieni generis hominem uiderint, ipsius lingua appellabunt eum & parentum eius & cognatorum nomina, blandientes sermone ut decipiant eos & perdant. Cumque conprehenerint eos perdunt eos & comedunt, & postea conprehendunt caput ipsius hominis quem commederunt [sic] & super ipsum plorant.

Ðonne is sum ealand on þære readan sæ, þær is mon cynn þæt is mid us donestre genemned, þa syndon geweaxene swa frihteras fram þam heafde oð ðone nafelan, & se oðer dæl bið mannerlice ge lic & hi cunnon eall mennisc gereord. Þonne hi fremdes kynnes mann geseoð [þo]nne nemnað hi hine & his magas cuþra manna naman & mid leaslicum wordum hine beswicað & hine onfoð & þænne æfter þan hi hine fretað ealne buton his heafde & þonne sittað & wepað ofer ðam heafde.

(There is a an island in the Red Sea in which a type of human which is called by us Donestre, as if divine from the head to the navel, as if humans in the rest of the body in the likeness of humans, they speak in the languages of all nations; when they see a person of a foreign race, they will call upon them in their and language and the names of their parents and kin, flattering with language so that they are deceived and killed; and when they seize them, they kill and eat them, and afterward they take the head of the person whom they have eaten and cry over it.)

But the Donestre were not crocodiles. The legend attaches to the reptiles by c.1265 when it is mentioned in Brunetto Latini’s Li Livres dou Treasure. About a hundred years later it appears in Mandeville’s Travels. Sir John Mandeville was a fictitious English knight who supposedly traveled the world recording the wondrous things and people he saw. In actuality, the author, whoever that was, probably never traveled, assembling the text from various traveler’s tales and legends and from their own imagination. Appearing in the late fourteenth century, first in French and then English, the text was enormously popular, appearing in over 250 extant manuscripts in various languages:

En ceo pays et par toute Ynde y ad grant foisoun des cocodrilles, c’est une manere des longes serpentz si qe jeo vous ay dit cea en ariere, et par nuyt elles habitent en l’eawe, et par jour sur terre en roches et en caves, et ne mangent point par tout l’yver, ancis gisent en agone si come font les serpentz. Ceste serpent occist les gentz et les mangent en plorant.

In þat contre & be all ynde ben gret plentee of COKODRILLES, þat is in a maner of a long serpent as I have seyd before. And in the nyght þei dwellen in the water & on the day vpon the lond in roches & in Caues. And þei ete no mete in all the wynter, but þei lyȝn as in a drem, as don the serpentes. Þeise serpentes slen men & þei eten hem wepynge.

(In that country & and in all India is a great plenty of crocodiles, that are like the long serpent that I have mentioned before. And in the night they dwell in the water & in the day upon the land in rocks and in caves. And they eat no food in all the winter, but they lie as if in a dream, as do the serpents. These serpents slay men & they eat them weeping.)

The version where the crocodile lures its prey to it by feigning sadness and pity is recorded in Richard Hakluyt’s 1589 Principall Navigations. The anecdote appears in the account of John Hawkins’s 1564 expedition to the Americas:

In this riuer we saw many crocodils of sundry bignesses, but some as big as a boat, with 4. feet, a long broad mouth, & a long taile, whose skin is so hard, that a sword wil not pierce it. His nature is to liue out of the water as a frog doth, but he is a great deuouer, & spareth neither fish, which is his common food, nor beasts, nor men, if he take them, as the proofe thereof was knowen by a Negroe, who as he was filling water in the riuer was by one of them caried cleane away, and neuer seene after. His nature is euer when he would haue his praie, to crie, and sobbe like a christian bodie, to prouoke them to come come to him, and then hee snatcheth at them, and thereupon came this prouerbe that is applied unto women when they weep Lachrymaæ Crocodili, the meaning whereof is, that as the Crocadile when he crieth, goeth then about most to deceiue, so doth a woman most commonly when she weepeth.

And Henry Cockeram’s 1623 English dictionary includes a description of the crocodile that sounds an awful lot like the early medieval description of the Donestre:

Crocodile, a beast hatched of an egge, yet some of them grow to a great bignesse, as 10. 20. or 30. foot in length: it hath cruell teeth and scaly back, with very sharpe clawes on his feete: if it see a man afraid of him, it will eagerly pursue him, but on the contrary, if he be assaulted he wil shun him. Hauing eate[n] the body of a man, it will weepe ouer the head, but in fine eate the head also: thence came the Prouerb, he shed. Crocodile teares, viz. fayned teares.

The phrase crocodile tears itself appears by 1563, when it is used by Edmund Grindal, bishop of London, in reference to a man who had been excommunicated:

And yet I assure your Lordship, I doubt much of his Zeal. For now after so long Trial, and good Observation of his Proceedings herein, I begin to fear, lest his Humility in Words be a counterfeit Humility, and his Tears, Crocodile Tears, altho’ I my self was much moved with them at the first.

And while he never used the phrase itself, Shakespeare made reference to the notion of crocodile tears in several of his plays, perhaps most notably in his 1603 Othello, Act 4, Scene 1, where Othello dismisses Desdemona’s weeping as false:

Oh diuell, diuell:

If that the Earth could teeme with womans teares,

Each drop she falls, would proue a Crocodile.

Shakespeare’s references to crocodile tears have undoubtedly helped keep the idea and phrase in the popular imagination.

Sources:

Cockayne, Oswald, ed. “De rebus in oriente mirabilibus.” Narratiunculae Anglice Conscriptae. London: John R. Smith, 1861, 65. HathiTrust Digital Library.

Cockeram, Henry. The English Dictionarie. London: Eliot’s Court Press for Edmund Weaver, 1623, part 3, unnumbered 1–2. Early English Books Online.

Fulk, R.D., ed. The Beowulf Manuscript. Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library 3. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2010, 24. London, British Library, Cotton MS Vitellius A.xv, fol. 96v–106v.

Hakluyt, Richard. The Principall Navigations, Voiages and Discoveries of the English Nation. London: George Bishop and Ralph Newberie, 1589, 534–35. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Hamelius, P. Mandeville’s Travels, vol. 1 of 2. Early English Text Society, OS 153. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, 1919, 192. HathTrust Digital Archive. London, British Library, MS Cotton Titus C.16.

Latini, Brunetto. The Book of the Treasure—Li Livres dou Tresor. Paul Barrette and Spurgeon Baldwin, trans. Garland Library of Medieval Literature 90. Series B. New York: Routledge, 1993.

Mandeville, Jean De. Le Livre des Merveilles du Monde. Deluz, Christiane, ed. Sources d’Histoire Médiévale. Paris: CNRS 31, 2000, 452.

Middle English Dictionary, 2019, s.v. cocodril, n.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. crocodile, n.

De rebus in Oriente miribilibus (The Wonders of the East). London, British Library, Cotton MS Tiberius B.v., fol. 83r–v.

Shakespeare, William. Othello. Mr. William Shakespeares Comedie, Histories, & Tragedies (First Folio, New South Wales). London: Isaac Jaggard and Edward Blount, 1623, 4.1, 330.

Strype, John. The History of the Life and Acts of the Most Reverend Father in God, Edmund Grindal. London: John Hartley, 1710, 78. Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO).

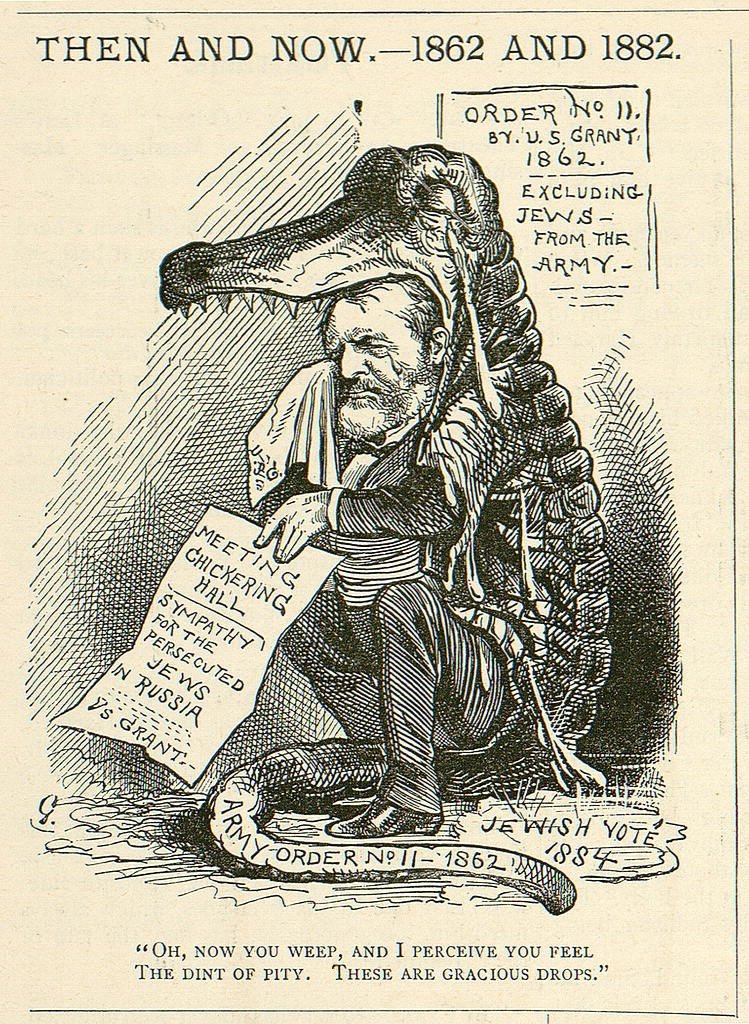

Image credits: Bernard Gillam, 1882, Puck magazine. Public domain image.

De rebus in Oriente miribilibus (The Wonders of the East). London, British Library, Cotton MS Tiberius B.v., fol. 83v.