24 March 2021

Kit and caboodle is an American slang phrase meaning all, the entirety of something. The constituent elements, however, make little sense to the present-day ear. We know kit as a collection of gear or equipment, but that makes little sense in this context. And caboodle sounds like a nonsense word. But the history of the phrase is one of gradual accretion of elements going back over a thousand years.

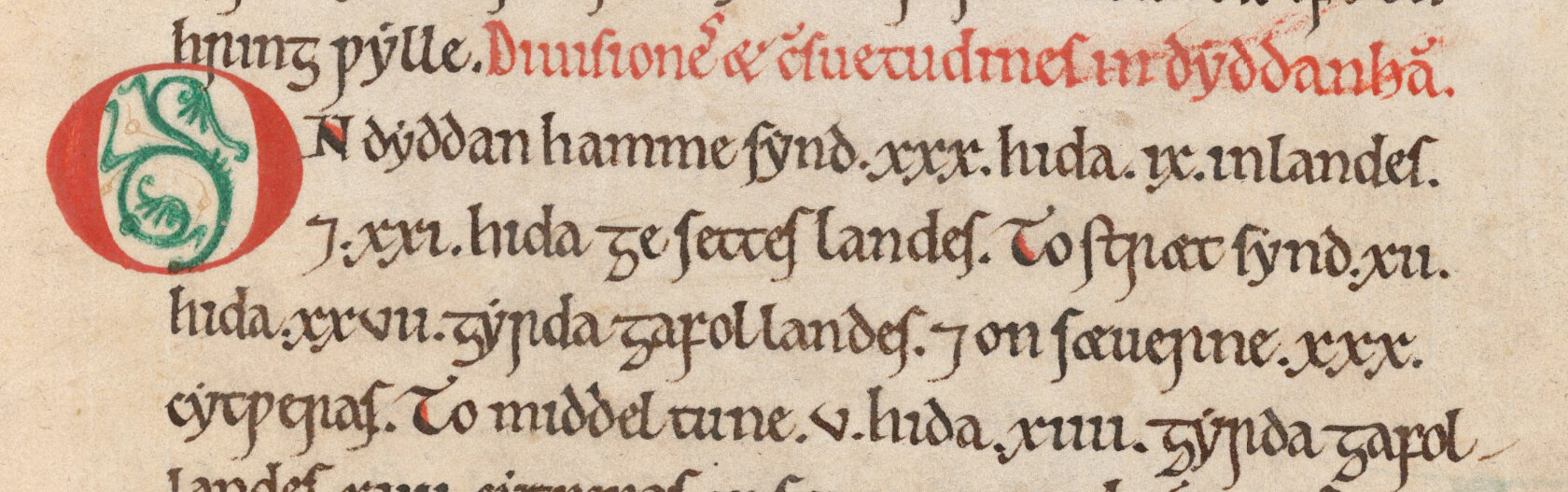

Kit dates back to Old English. The word *cyt meaning a basket or container probably existed but isn’t recorded in the surviving record. But the compound cytwer, meaning a dam, weir, or barrier fitted with baskets for catching fish is recorded. We see it in a 956 C.E. charter granting land to the abbey at Bath:

On Dyddanhamme synd . xxx . hida — . ix . inlandes & . xxi hida gesettes landes. To Stræt synd . xii . hida . xxvii . gyrda gafollandes . & on Sæuerne . xxx . cytweras.

(In Tidenham there are 30 hides—9 of estate land & 21 hides of tenanted land. At Stroat there are 12 hides [including] 27 gyrds of leased land—and on the Severn River are 30 basket-weirs.)

Hide and gyrd are measures of land, the exact size varying with the locality. A hide would be large enough to support a single household, typically about 120 acres or 12 hectares, and a gyrd was one fourth of a hide, about 30 acres or 3 hectares.

Kit in the sense of a barrel or other container dates to at least 1362, when it appears in an inventory of property belonging to the monastery at Jarrow-Monkwearmouth:

Item in bracina sunt ij. plumba, j. maskfatt cum pertinentiis, iiij. gilfattes quarum ij. novæ et ij. veteres, iij. fattes debiles, iij. tubbes, ij. tynæ, j. bona et alia debilis, ij. melfattes, j. temes nova, iij. bulteclathes bonæ, j. melsyf, xj. barelli pro servisia, ij. troues pro servisia conservanda, iij. meles bonæ, ij. wortdisses bonæ, ij. collokes et j. kytt pro vaccis mulgendis, j. kyrne, j. furgum de ferro, j. colrake de ferro bonum.

(Item. In the kitchen are 2 lead vessels; 1 mash vat with related items; 4 wort vats of which 2 are new and 2 old; 3 poor-quality vats; 3 tubs; 2 tins, 1 good and the other bad; 2 honey vats; 1 new sieve; 3 good sifting cloths, 1 honey sieve, 11 barrels for beer, 2 vessels for preserving beer, 3 good containers, 2 good wort dishes, 2 tankards and 1 kit for cow’s milk, 1 churn, 1 poker for the fire, 1 good ash-rake for the fire.)

The meaning of kit eventually transferred over to the contents of the container. Much like we might say a “barrel of ___” or a “passel of ___,” one might say a “kit of ____.” And by 1784 we see the phrase the whole kit, meaning the entirety of something, the entire group. From James Hartley’s The History of the Westminster Election of that year:

I saw the constables all bear down in a full body from Wood's Hotel, which is King-street end [sic] of the Hustings down to the pump; when they came to the pump, I was standing facing the spot, and there came a head constable with the whole kit of the constables, each had a black staff with silver tipped at each end, and a crown at top; it was about two feet long, I was standing there, and if I had not moved I should have been knocked down by it.

And the early slang lexicographer Francis Grose recorded it in his 1785 A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, although he got the etymology wrong:

KIT, a dancing master, so called from his kit, or cittern, (a small fiddle) which dancing masters always carry about with them, to play to their scholars; the kit, is likewise the whole of a soldier's necessaries, the content of his knapsack, and is used also to express the whole of different commodities; here take the whole kit, i.e. take all.

And there is this article about an assault on and alleged robbery of a Jewish watch salesman from 1798. Not only does it show the use of the whole kit, it is also indicative of antisemitism prevalent in Britain at the time:

The Magistrates took much pains to develope this mysterious affair, and were of the opinion that there was no intention of robbery, and in fact, it was doubtful if any watch was lost; but of the assault they had no doubt, and bound them to that only, which made Shylock vehemently exclaim at the Office door—“Who is to pay me for my Vatch? Oh! my poor Vatch, d—n mine eyes if I don’t get payment for mine Vatch, but I will indict the whole kit of you!”

Boodle, on the other hand, makes a later appearance than kit. It’s a borrowing of the Dutch boedel, meaning the moveable goods of a person or a heap or disordered collection of things. It makes an appearance in the seventeenth century, but that seems to be an isolated or short-lived borrowing. From Francis Markham’s 1625 The Book of Honour:

And questionlesse, there are most infallible Reasons, why extraordinary respect should be giuen to this place of Embassador, both in regard of their election, being men curiously and carefully chosen out (from all the Buddle, and masse of great ones) for their aprooued wisedome, and experience.

The word was apparently reborrowed into American English in the early nineteenth century. The editors of the New Hampshire Patriot published this New Year’s poem on 4 January 1814 recounting the events of the past year. One stanza represents the Federalist Party’s sweeping of state and federal offices, driving out Democratic-Republican office holders. Concord is the state capital:

The Junto defeated, from Concord retreated,

The Governor too with his old cock up hat,

While the loud execration of both State and nation,

Pursu’d the whole boodle on this side and that.

And in an 18 July 1827 letter, humorist George W. Arnold, writing in the voice of a character named Joe Strickland, had this to say:

Then he dug under ground un got intu the Phultun banck, un turnd out the hol boodle ov um, got awl the munny, un then lafft at um, the loryars awl the tyme drivin at him, but tha koud’nt get hold on him—he waz jist like Padda’s Phlee, kase when tha put ther finger on him he was’nt there.

At some point the ca- was added to boodle, perhaps for emphasis and because of the old comic truism that words that begin with /k/ are inherently funny. We see the whole caboodle in an April 1839 account of the trial of Alexander Stewart (the prisoner) for conspiracy to kidnap Canadian terrorist Benjamin Lett, who had taken refuge in the United States, and return him to Canada. Stewart was accused of being a spy for Canada, and his associate was James Sparks:

Witness continued—To get Lett across Sparks proposed to get him drunk—to mix laudanum with his liquor—or knock him down—saw nothing prepared for the purpose—got half a gallon of rum for his (witness’s) own use. If witness had gone into the plan a part of the rum might have been used—told Lett not to drink with prisoner and Sparks at any time. Witness saw a letter from Gov. Arthur’s son to the prisoner, which stated that a reward of $4000 would be given for his delivery in Canada.

(Prisoner—Bob! I’ll tell you the whole caboodle of the scrape! I am willing to act as a witness. I don’t care a damn! Put me as a witness if you like.)

Ten years later, on 31 March 1849 the Vermont newspaper The State Banner combined the two in the whole kit and boodle in an article about politician Horace Greeley. The rhetoric of the article should be familiar to those familiar with American politics today:

Horace Greely, when the whole kit and boodle of the honorable thieves in Congress turned upon him, and branded him as no gentlemen [sic], owned up in the following Ben Franklin style. Well done, Horace!

“I know very well—I knew from the first what a low, contemptible, demagoguing business this of attempting to save public money always is. It is not a task for gentlemen—it is esteemed rather disreputable for editors. Your gentlemanly work is spending—lavishing—distributing—taking. Savings are always such vulgar, beggarly, two-penny affairs—there is a sorry and stingy look about them most repugnant to all gentlemanly instincts. And besides they never happen to hit the right place, it is always ‘strike higher!’ ‘strike lower!’—to be generous with other people’s money—generous to self and friends especially, that is the way to be popular and commending. Go ahead, and never care for expense!—if your debts become inconvenient you can repudiate and blackguard your creditors as descended from Judas Iscariot! Ah! Mr Chairman, I was not rocked in the cradle of gentility!”

Finally, by 1870 we seen the complete phrase the whole kit and caboodle in Henry Stiles’s 1870 History of the City of Brooklyn:

A line of stages, it was true, pretended (as it had, for several years), to keep up the connection between the two points; but it was managed in the most irregular manner. Poor stages, and poorer horses; easy drivers, who deviated from the route, hither or thither, obedient to the call of a handkerchief fluttering from a window blind, or the " halloo!" of a passenger anywhere in sight. Mr. Queen, therefore, purchased the entire "kit and caboodle" of the stage company; put on entirely new conveyances, horses, and equipments, and started what he intended should be an omnibus line to Bedford, running regularly, on a carefully arranged time table

A rather long path from early medieval fishing weirs on the Severn river.

Sources:

“Bounds and Customs of Tidenham, Glous.” (Sawyer 1555). The Electronic Sawyer. Cambridge, Corpus Christi College MS 111.

Dictionary of Old English: A to I, 2018, cyt-wer.

“Editor’s New Year’s Address” (1 January 1814) New Hampshire Patriot (Concord), 4 January 1814, 4. NewsBank: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, 2021, s.v. whole kit, n.

Grose, Francis. A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue. London: S. Hooper, 1785. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Hartley, James. The History of the Westminster Election. London: 1784, 403. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

The Inventories and Account Rolls of the Benedictine Houses or Cells of Jarrow and Monk-Wearmouth. Publications of the Surtees Society, 29. Durham: George Andrews, 1854, 159. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Mackenzie, James. “British Spies Unmasked!!” Mackenzie’s Gazette (Rochester, New York), 20 April 1839, 3. NewsBank: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Markham, Francis. “The Argument of Embassadors.” The Book of Honour. London: Augustine Matthewes and John Norton, 1625, 125. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Middle English Dictionary, 2019, s.v. kit(te, n.(1).

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, September 2018, s.v. boodle, n.1; second edition, 1989, s.v. caboodle, n., kit, n.1.

“Police Offices.” Oracle, and the Daily Advertiser (London), 27 October 1798, 7. Gale Primary Sources: Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection.

The State Banner (East Bennington, Vermont), 31 March 1849, 2. NewsBank: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Stiles, Henry R. A History of the City of Brooklyn, vol. 3 of 3. Brooklyn: 1870, 569. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Strickland, Joe (pseudonym of George W. Arnold). Letter (18 July 1827). In Allen Walker Read, “The World of Joe Strickland.” Journal of American Folklore, 76.302, October–December 1963, 289. JSTOR.

Image credit: Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 111: The Bath Cartulary and related items, Parker on the Web, p. 72.