19 July 2021

To think outside the box is to disregard artificial constraints on creativity, to engage in unconventional thought processes. The phrase as we know it arises from a puzzle used as an exercise in creative thinking. The phrase also has a precursor with slightly different wording: think outside the dots.

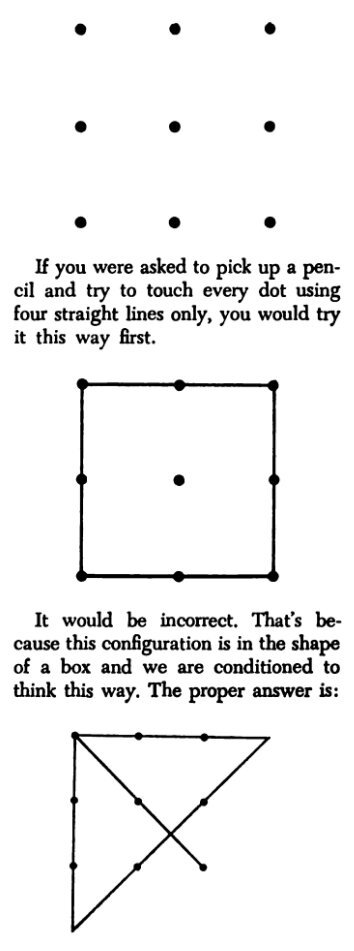

In the puzzle, nine dots are arranged on a 3×3 grid, and the participants are asked to connect the dots with four straight lines and without lifting the pencil from the paper. Most participants will keep their lines within the box defined by the grid, but the only solution, as shown in the accompanying illustration, is to extend the lines beyond the boundaries of the grid. The point being the restriction of keeping within the boundaries is an artificial one, imposed by the participants themselves and by extension that other, real-world, problems can be solved if only people disregard analogous artificial constraints.

While the phrase arose in the middle of the twentieth century, the metaphor underlying it is quite old, older than the puzzle itself. For example, there is this from an 1888 account of the British Parliament that uses think outside the lines:

He said that, having changed at Mr. Gladstone’s signal, from all but unanimous repudiation of Home Rule in 1885, to its enthusiastic support in 1887, the Liberal party became a one-man party, which scarcely ventured to think outside the lines prescribed by its dictator.

Other such framing of the metaphor can undoubtedly be found.

The earliest reference to the puzzle that I have found is in a religion column by the Rev. John F. Anderson in the Dallas Morning News of 30 October 1954. Anderson relates an account, real or imagined, of a Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor using the puzzle in a class with graduate students. He uses go outside the dots; the think would come a bit later:

“But prof,” one student protested, “that is not fair. You went outside the dots.”

“Who said you couldn’t?” was his disarming reply.

“Young men,” he continued, “we are not here to go through old routines. Don’t let your thinking be contained in a small square of knowledge. Learn to go “outside the dots” and you may be the one to solve some of man’s most puzzling problems.

A later use (see below) of the phrase by another preacher, makes me think the anecdote may have circulated in volumes of sermon illustrations that provide preachers with ideas for sermons.

But within a decade the puzzle and its accompanying lesson starts appearing in business management courses. From an article about just such a course in the 18 April 1963 Springfield Union:

We must ask ourselves: “What are the actual boundaries of the problem?” Perhaps, some of you have seen this little problem before. Here are nine dots, arranged in a square[.]

The problem is to connect all the dots by drawing four straight lines without removing the chalk from the black board and without retracing. Try it!

Did you first attempt to draw the lines within the boundaries of the nine dots? There is no rule that requires it. The solution demands that some of the lines extend into the space outside the dots.

And again from the Dallas Morning News, this time of 15 May 1964, is this list of courses at a conference of women accountants:

Speakers and their subjects will be Miss Ouida Albright of Fort Worth, Effective Use of Your Time; Mrs. Lauer, Managerial Accounting; Miss Ruth Reynolds of Tulsa, Okla., Internal Controls; Mrs. Engel, How to Conduct a Conference; Mrs. Mary Crowley, Going Outside the Dots, and C.L. Bateman of Tulsa, Cost Reduction in the Office.

But we don’t have the full think outside the dots. That comes by 23 May 1970 in a column in the Ottawa Journal. It uses the phrase, but the column makes no explicit reference to or explanation of the puzzle. The writer assumes the reader is familiar with it, or at least with the concept:

The problem, says William Davd [sic] Hopper, is to think “outside the dots” about questions of how to feed a hungry world.

He means that the need is to think imaginatively, creatively about the development of less-developed countries, and not merely to keep pouring more money and technology into patterns of foreign aid established, not very successfully, over the past 20 years.

While the column co-locates all the words in the phrase, its use of quotation marks separates think from outside the dots, indicating that the think was not yet part of the standard phrasing.

We get the complete phrase by 6 July 1980, when it appears in another newspaper column, this time in the Miami Herald:

Mrs. Roe was my English teacher in junior high school in Miami. One dictum ruled her classroom—and, I suspect, her life—and occasionally in a fit of passion she’d scrawl on the blackboard in letters a foot high: THINK OUTSIDE THE DOTS!

More often she uttered it—hurled it, really—and everyone came to know the pattern, to watch for it, to even relish it. She’d ask a question, get no response. A minute would pass while she still stared at us: a hush would fall. Then all at once she’d cry, “Think outside the dots! Think outside the dots!”

Think outside the dots is still in use, although it is far less common than think outside the box. Here is a more recent example of think outside the dots from the Trenton Evening Times of 28 February 2010:

Challenge brings success

Architect J. Robert Hillier says you have to “think outside the dots”[...]

“It’s a great puzzle,” he explains, brandishing a pencil and solving the challenge. “But you have to go outside the dots. You have to extend the line beyond the rectangle. That the trouble with so many people.

“When people are confronted with the puzzle—any puzzle—they try to stay inside those dots. And the key to beating it,” Hillier adds with a smile, “is to go outside.”

The box wording can be traced to a 26 October 1969 newspaper column by preacher and self-help guru Norman Vincent Peale. Peale was enormously popular and influential, and his column would have been widely syndicated and read, and he is certainly responsible for much of the phrase’s popularity. Although, as with outside the dots, he doesn’t use the full phrasing of think outside the box:

There is one particular puzzle you may have seen. It’s a drawing of a box with some dots in it, and the idea is to connect all the dots by using only four lines. You can work and work on that puzzle, but the only way to solve it is to draw the lines to [sic] they connect outside the box. It’s simple, once you realize the principle behind it. But if you keep trying to solve it inside the box, you’ll never be able to master that particular puzzle.

That puzzle represents the way a lot of people think. They get caught up inside the box of their own lives. You’ve got to approach any problem objectively. Stand back and see it for exactly what it is. From a little distance, you can see it a lot more clearly. Try and get a different perspective, a fresh point of view. Step outside the box your problem has created within you and come at it from a different direction.

The full phrase think outside the box dates to a few years later and the September 1971 issue of the journal Data Management:

THINK OUTSIDE THE BOX

If you have kept your thinking process operating inside the lines and boxes, then you are normal and average, for that is the way your thinking has been programmed. Unfortunately, we have accepted thought process limitations that are artificial. They are man-made and do not exist in reality.

And as with the dots version, within a decade the phrase think outside the box could be used without explicit reference to the puzzle, assuming the readers would understand what was meant. From a syndicated medical column of 23 March 1978 by Dr. Robert Mendelsohn:

Some of my best teachers have been those who utilize the techniques of shock and surprise to rouse me out of conventional habits of thought, forcing me to question accepted teaching and stimulating me to “think outside the box.”

Sources:

Anderson, John F. “Down to Earth.” Dallas Morning News (Texas), 30 October 1954, 1. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

The Annual Register: A Review of Public Events at Home and Abroad for the Year 1887. London: Rivingtons, 1888, 168. Google Books.

Barnebey, Faith. “On the Draft: ‘Think Outside the Dots!’” Miami Herald (Florida), 6 July 1980, 1–E. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

“Challenge Brings Success.” Trenton Evening Times (New Jersey), 28 February 2010, D1, D3. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

“Inventiveness, Motivation, Training Needs of Scientists.” Springfield Union (Massachusetts), 18 April 1963, 52. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Mendelsohn, Robert. “People’s Doctor.” Times-Picayune (New Orleans) (syndicated), 23 March 1978, 4–7. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Notaro, Michael R. “Management of Personnel: Organizational Patterns and Techniques.” Data Management, 9.9, September 1971, 77. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

O’Toole, Garson. “Antedating of ‘Outside the Box.’” ADS-L, 3 May 2010.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, June 2021, s.v. box, n.2.

Peale, Norman Vincent. “Confident Living: Never Give Up.” Springfield Republican (Massachusetts), 26 October 1969, 23. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Tréguer, Pascal. “‘To Think Outside the Box’: Meaning and Origin.” Wordhistories.net . 28 April 2021.

Westell, Anthony. “Ottawa in Perspective: Canada Entering Big League in Research.” Ottawa Journal, 23 May 1970, 7. Newspapers.com.

“Women Accountants to Sponsor Seminar.” Dallas Morning News (Texas), 15 May 1964, 3–2. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Image credit: Notaro, Michael R. “Management of Personnel: Organizational Patterns and Techniques.” Data Management, 9.9, September 1971, 77. HathiTrust Digital Archive. Fair use of a copyrighted image to illustrate the topic under discussion.