30 August 2021

Wog is a racist slur, chiefly found in British speech. The word is used as a disparaging term for anyone who isn’t English, especially a person with darker skin or Asian facial features. It’s a clipping of golliwog, the name for a type of black-faced doll popular at the turn of the twentieth century. Golliwog, in turn, is a variation on pollywog.

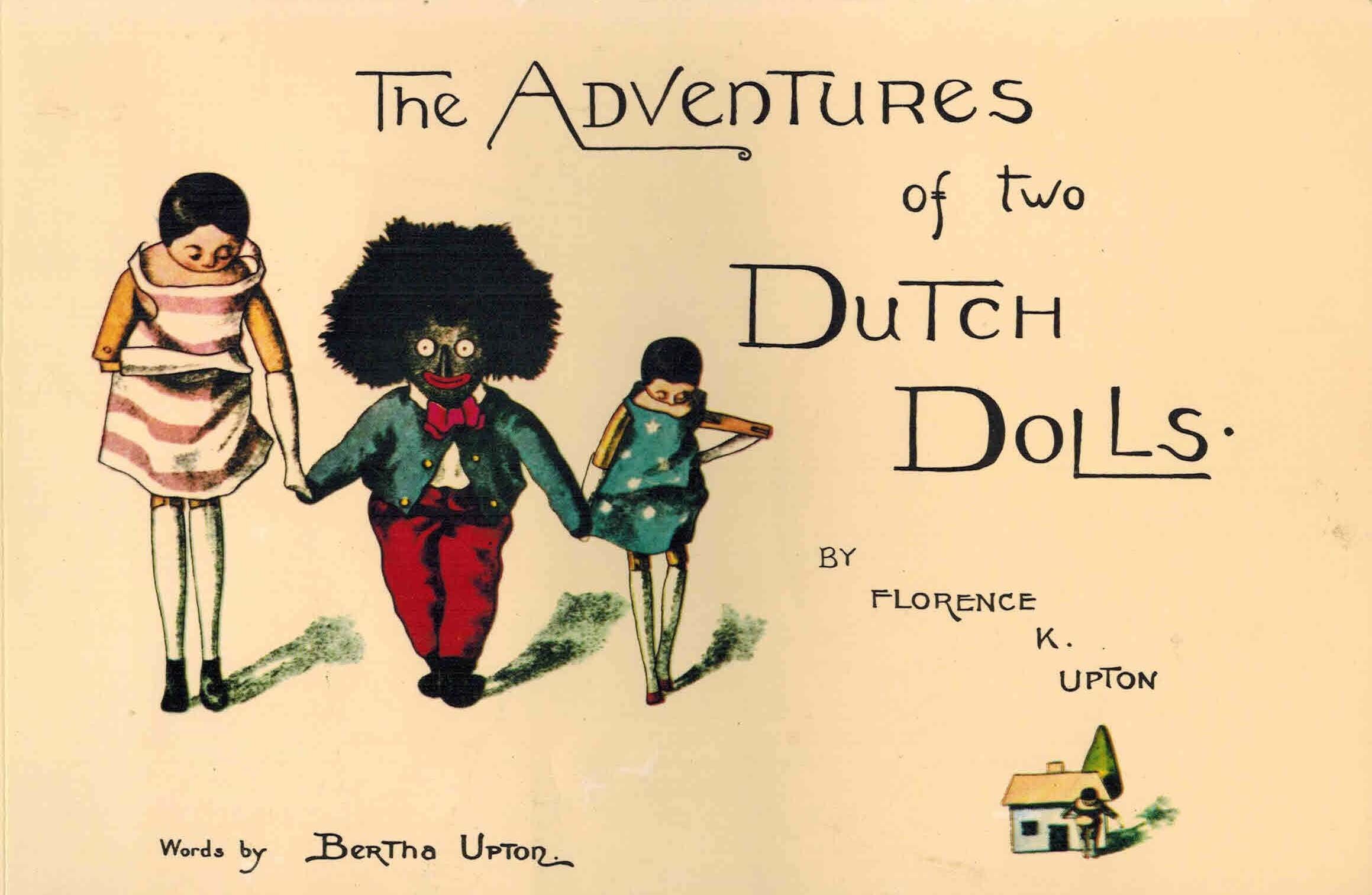

Golliwog was coined by Florence Kate Upton and first appeared in print in the 1895 children’s book The Adventures of Two Dutch Dolls and a “Golliwogg,” which she wrote in collaboration with her mother, Bertha Upton. Bertha wrote the text and Florence supplied the illustrations. Her depiction of the golliwog was very much in the style of a blackface minstrel performer, dark skin with an afro hair style and wearing a blue jacket with tails and red trousers and bowtie. This passage introduces the golliwog:

“Just one leap more!” cries Sarah Jane,

“This fills my wildest dream!”

E’en as she spoke,

Peg’ Deutchland broke

Into a piercing scream.Then all look round, as well they may

To see a horrid sight!

The blackest gnome

Stands there alone,

They scatter in their fright.With kindly smile he nearer draws;

Begs them to feel no fear.

“What is your name?”

Cries Sarah Jane;

“The ‘Golliwogg’ my dear.”

The book was wildly successful on both sides of the Atlantic, and the Uptons would go on to publish a series of books featuring the character of the golliwogg. The books also inspired a lucrative market in golliwogg dolls.

There are many early references to the books and golliwogg dolls at the turn of the twentieth century, but it wasn’t long before golliwog, dropping the second terminal <g>, began to be used as a term for a foreigner, especially a dark-skinned one. There is this reference which appears in a short story published in the Augusta Chronicle of 30 September 1901. Exactly what golliwog refers to here is lost to us today, but it’s certainly not complimentary:

“Mrs. Jack Daring wears a woollen petticoat under her golf skirt,” interrupted Mrs. Max, “although under her waist she wears a paper waistcoat, which she says is warmer than a golf cape, but that is because she likes to show her figure; though Polly Stangner says Mrs. Jack creaks like a golliwog when she swings a club.”

A year later, this description of the punching power of boxer Robert Fitzsimmons appears in the 7 September 1902 Atlanta Journal. It mentions the Irish boxer Peter Maher, nicknamed the Galway Golliwog. In 1902, the Irish, while ranking above those of African or Asian descent in racist categorization schemes, were not considered to be equal to “whites” in American society:

The Fitzsimmons knockout drops were found most efficacious by these persons, and were used by all the notables of the ring, including “Jack” Dempsey, the pet of the Golden Gate; Peter Maher, the Galway Golliwog, and “Billie” McCarthy, the Soft Snap of the Sand Lots[.] In the face of the Fitzsimmons upper cut these gentlemen all went groggy in short order, and the coming champion ventured east in search of soft marks for his ever ready dukes.

And there is this from a short story in the Albany, New York Times-Union. The use of golliwog is in the sense of the doll, but the descriptor brute indicates how people viewed the character. The story is about a talking baby, who at one point says:

You sit glaring at me for ten minutes like—like that brute of a Golliwog I keep upstairs, and then you begin dozing over the fire for all the world like you’d just had a couple of ounces of food. And you expect me to say nothing.

And for unabashed racism, it is hard to top this use of golliwog to refer to a Polynesian man that appeared in short story published in the Philadelphia Inquirer of 28 February 1909:

One member of the Braddock household was not included in the general staff, being a mere appendage of the Professor himself. This was a dwarfish, mis-shapen Kanaka, a pigmy in height, but a giant in breadth, with short, thick legs, and long powerful arms. He had a large head, and somewhat handsome face, with melancholy black eyes and fine set of white teeth.

Like most Polynesians, his skin was of a pale bronze and elaborately tattooed, even the cheeks and chin being scored with curves of straight lines of mystical import.

“I do not like that Golliwog,” breathed Mrs. Jasher to her host, when the Cockatoo was at the sideboard. “He gives me the creeps.”

“Imagination, my dear lady, pure imagination. Why should we not have a picturesque animal to wait upon us?”

The clipping to wog happens a few years later. The earliest recorded uses are in World War I soldier slang published shortly after the war. There is this from Lionel James’s 1921 The History of King Edward’s Horse in a reference to events of 1917:

The King Edward’s Horse called the Indian Cavalry “The Wogs”—which is the diminutive of “Golliwogs,”—a description that was very apt of these dark apparitions in khaki and tin-hats.

The clipped form wog never caught on in American speech, and golliwog dropped out of American speech as memories of the books and dolls faded. But both continue as racist slurs to this day in British speech to this day.

The disappearance of the Uptons’ character from popular memory made room for speculation as to the origin of wog, and several false acronymic explanations developed to justify the term. The most common are westernized / worthy / wily / wonderful oriental gentleman or working on government service, this last supposedly stenciled on the shirts of Egyptian workers on the Suez Canal. Of course, these explanations are all false, with no evidentiary support.

Sources:

Elverson, James. “The Green Mummy.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 28 February 1909, 6. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

James, Lionel. The History of King Edward’s Horse. London: Sifton, Praed, 1921, 128. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Jenkins, Wilberforce. “Who’s What and Why in America.” Atlanta Journal, 7 September 1902, Feature Section 2. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

“Our Daily Story: It and I.” Times-Union (Albany, New York), 21 June 1904, 6. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, December 2016, modified March 2020, s.v. wog, n.1.; second edition, 1989, s.v. golliwog, n.

Townsend, Edward W. “Chronicle’s Daily Short Story: Maj. Max’s Ghost.” Augusta Chronicle (Georgia), 30 September 1901, 5. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Upton, Bertha. The Adventures of Two Dutch Dolls and a “Golliwogg.” Florence K. Upton, illus. Boston: De Wolfe, Fiske, and Co., 1895. Project Gutenberg.

Image credit: Florence K. Upton. The Adventures of Two Dutch Dolls and a “Golliwog.” Boston: De Wolfe, Fiske, and Co., 1895. Public domain image.