3 December 2020

The oft-told tale is that U.S. Marine Lieutenant Colonel Evans Carlson introduced the phrase gung-ho, meaning enthusiastic, eager, into the English language. The story has a germ of truth in that Carlson did a lot to popularize the phrase and associate it with the military, but he did not introduce the phrase into English, and it had a degree of currency among English speakers before he came along.

Gung-ho comes from the Mandarin 工合 or gōnghé. It is a clipping of the name of the Chinese Industrial Cooperatives, 工業合作社 or Gōngyè Hézuòshè, which was a movement started in 1937 in Shanghai to develop grassroots industry in China in response to the Japanese invasion. The idea was to mobilize small groups of displaced and unemployed workers under a framework of a larger infrastructure.

The phrase in this context first appeared in English-language newspapers in 1939. From the Washington, D.C. Sunday Star of 19 November 1939:

A red blunted triangle inscribed with the white character “Kung Ho,” meaning “We Work Together,” is the insignia of these Chinese industrials. It appears upon the some 50 products they turn out.

The gung-ho spelling appeared in a 19 February 1941 article in the daily version of the same paper:

If Wendell Willkie carries out his reported plans to visit China in pursuance of his zest for personal observation of conditions in a war-torn world, it’s believed that study of China’s so-call “guerilla industry” would be one of the magnets drawing him thither. It is the great Chines industrial co-operative scheme known as Gung-ho, which means “work together.”

And Helen Foster Snow, under the pseudonym Nym Wales, one of the expatriates who helped organize the C.I.C. movement, penned a 1941 book on the topic, in which she gives the origin of the phrase:

In Chinese the term is Chung Kuo Kung Yeh Ho Tso Hsieh Hui—Chinese Industrial Cooperative Association. It is popularly called “Kung Ho” or “Gung Ho” from the two characters meaning “Work Together,” which appear in its triangle trademark. In English is it referred to as the “C.I.C. Movement.”

Later in the book, she describes the movement’s popularity:

Again one who had been a child worker at the age of ten, and had had twenty years of city factory life, with its strikes, its long hours, its trickery and so on. And how much the C.I.C. meant to him and his whole co-op. He has made a “Kung Ho” in grass outside his co-op ... An ex-school teacher from occupied territory, and an ex-Red Cross man with famine work experience, and now chairman of a surgical gauze co-op. And so-on—they were an encouraging crowd.

“It was fun to pass a lone kid, doing his morning job by a grave mound, and singing lustily the co-op song, while he tied up the tapes around him—“All for One and One for All.”

“I have just come in after having an afternoon with Miss Jen— looking at some of her women's work. It is really good. We passed a bunch of six-year olds marching down the loess valley road from the school which was housed in a temple vacated by the soldiers because they wanted to help “kung ho.” The kids were singing “Ch'i Lai" in good kung-ho fashion.”

There was a newsreel about the C.I.C. movement in China that was shown in U.S. movie theaters, as evidenced by a 13 September 1941 advertisement in the San Francisco Examiner:

“Gung Ho”

(In Chinese “Work Together”)

With Regan “Tex” McCrary”

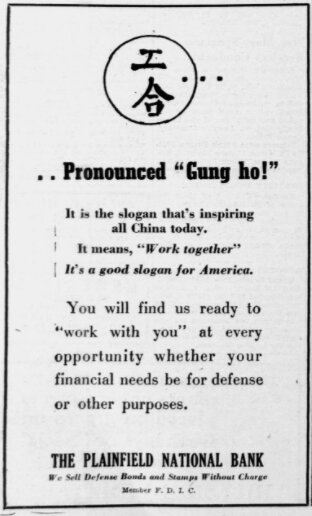

And a Plainfield, New Jersey bank even used gung-ho in a 20 September 1941 advertisement:

工合 ... Pronounced “Gung ho!”

It is the slogan that’s inspiring all China today.

It means, “Work together”

It’s a good slogan for America.

Here is where Carlson and the marines come in. Before the United States’ entry into WWII, Carlson had served several tours of duty in China, including one as a military observer to the Chinese army in its fight against the Japanese. His duties in this post included assessing Chinese industrial capacity, which is where he became familiar with and enamored by the C.I.C. movement. In February 1942, he was placed in command of the newly formed Second Marine Raider Battalion, a special operations or commando unit. He chose gung-ho as the unit’s motto.

On 17 August 1942, the Second Raider Battalion raided the island of Butaritari, known to the Americans as Makin Atoll, in the Gilbert Islands, and the action and Carlson’s unit received considerable press coverage over the following weeks. (The unit’s P.R. angle was helped by the fact that James Roosevelt, the president’s son, was Carlson’s executive officer.) For instance, this Associated Press piece appeared on 28 August 1942:

Colonel Carlson explained that in organizing the battalion he preached an old Chinese saying “Kung Ho,” which means “Work and Harmony.” This became the byword of the battalion.

And this International News Service piece on 8 September 1942:

“‘Gung Ho’ Battle Cry of Carlson Raiders.

WASHINGTON, Sept. 7 (INS)—The new battle cry of “Carlson’s Raiders,” who besieged the Japanese base on Makin island August 17, today is ‘Gung Ho,’ or in English, ‘Work Together.’”

There was even a 1943 Hollywood movie, starring Randolph Scott, made about the raid and titled Gung Ho!

As a result, gung ho was catapulted from a term that was somewhat familiar to some English speakers to one that was known by all, and the term’s focus and ethos also shifted from industry to the military.

Sources:

Associated Press. “Marines’ Island Raid Hit Japs Hard Blow.” Commercial Appeal (Memphis, Tennessee), 28 August 1942, 3. NewsBank: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Evans, Jessie Fant. “China’s Co-operatives Form a New Wall, Visitor Says.” Sunday Star (Washington, DC), 19 November 1939, C-10. NewsBank: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, 2020, s.v. gung-ho, adj.

International News Service. “‘Gung Ho’ Battle Cry of Carlson Raiders.” Times-Union (Albany, New York). 8 September 1942, 6. NewsBank: America’s Historical Newspapers.

“Newsreel Theater” (advertisement). Sacramento Bee, 7 March 1942, 15. NewsBank: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. gung ho, n.

Plainfield National Bank (advertisement). Plainfield Courier-News (New Jersey), 20 September 1941, 18. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Snow, Helen Foster (as Nym Wales). China Builds for Democracy: A Story of Cooperative Industry. New York: Modern Age Books, 1941, 43, 72. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Telenews (advertisement). San Francisco Examiner, 13 September 1941, 28. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Wile, Frederic William. “Washington Observations.” Evening Star (Washington, DC), 19 February 1941, A-13. NewsBank: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Photo credits: unknown photographer, 1940s, Spinning thread, China. Alley, Rewi, 1897-1987: Photographs. Ref: PA1-o-899-04-3. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand; Plainfield National Bank (advertisement). Plainfield Courier-News (New Jersey), 20 September 1941, 18. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.