12 March 2021

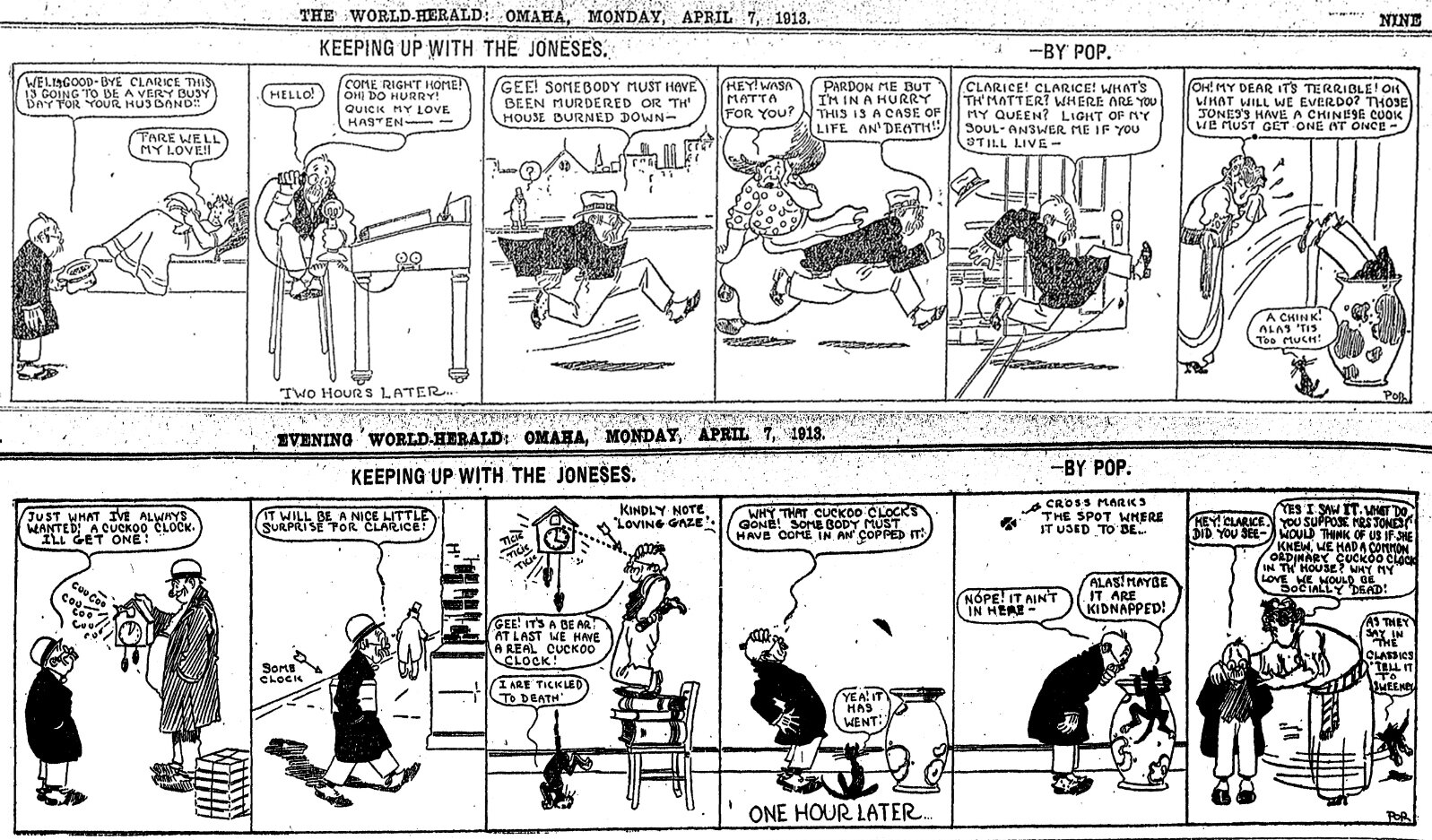

The phrase to keep up with the Joneses refers to maintaining social status and conspicuous material consumption equal to one’s peers or neighbors. The phrase is one of the few where we can pin down the exact origin. It comes from the name of a newspaper comic strip, Keeping Up with the Joneses by Arthur “Pop” Momand, that ran from 1913 to 1938.

Wikipedia gives a first publication date for the comic strip of 31 March 1913. The Oxford English Dictionary gives 1 April 1913 as its first citation. And the earliest digitized examples I have found are from 7 April 1913. The multiplicity of dates is not unusual, as syndicated comic strips are not always printed on the same day, the publication dates varying from paper to paper.

The phrase quickly entered into the American vocabulary. The earliest example not connected to the comic strip that I have found is in a misogynistic letter printed in the New-York Tribune on 7 December 1913 that argued against women’s suffrage and that a woman’s role was to stay at home and have babies:

My dear Mr. Beerbower, please take another look around you, and you will agree with me that, as a rule, where the women have plenty and live in idleness there are few or no children and where the women live in want and work hard there is a large flock of them. Should that not indicate that my assertion is right and you are wrong when you say, “Self-respecting women who are worth to become mothers,” etc. How many a man is not driven to the wall because his wife wants to keep it up with the Joneses!

Another less offensive use appears the next year in the Washington Bee, a Black newspaper in the District of Columbia. From the 7 March 1914 issue:

Still there were new found friends to step into the breach made by the departure of previous friends who had grown wise to exigencies. Still his fawning flattery, his outward appearing sincerity his insidious form of bribery in the shape of social teas, the tender in dainty cut glass receptacles of the “red, red wine,” attracting new moths to the flame that was sure to singe—still attracted some who hankered to be in “society” just in order to be “keeping up with the Joneses.”

While Pop Momand’s comic strip is largely forgotten, the phrase lives on.

Sources:

Mohr, George W. “Duties of Two Sexes Different” (30 November 1913). New-York Tribune, 7 December 1913, B10. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. keep, v.

Tyler, Ralph W (as R.W.T.). “Picture for Youth.” Washington Bee (District of Columbia), 7 March 1914, 1. NewsBank: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Image credits: Arthur “Pop” Momand, 1913. From the Omaha World-Herald and the Omaha Evening World-Herald for 7 April 1913, 9 & 10.