26 March 2021

Can too much sex lead to a nervous breakdown?

Nineteenth-century physicians seemed to think so. But to be fair, they identified overwork and stress as the most common cause of the problem. Today, nervous breakdown does not have a formal medical definition, and it does not appear in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. But it is used by laypeople and informally by medical professionals to refer to a person’s inability to carry out routine, daily functions due to stress.

The term nervous breakdown dates to at least 1866 and is undoubtedly older. The earliest use that I have found is a letter printed in a March 1866 American medical journal:

Three years ago I had an “attack” of lung fever, was salivated, and it was six months before I could do any work. I never fully recovered from the effects of the disease or the medicine, I do not know which. Last winter I had a nervous breakdown and was salivated again. Recovery was very slow, and, after two months’ convalescence, I overtaxed myself and broke down completely.

Use of the verb salivate here refers to using mercury to induce excessive salivation, which was thought to be indicated in the treatment of certain diseases. Mercury poisoning can, of course, produce many of the symptoms also associated with nervous breakdowns. But here we have a layperson using the term nervous breakdown, indicating that it was in circulation by 1866.

But it is in the 1870s that the term starts appearing with regularity in medical journals. It appears in the 11 January 1873 issue of The Lancet, with the causes of nervous breakdowns identified as overwork, especially too much “brain-work,” worry and the “cares and troubles” of modern life, and “sins against the laws of health.” This last circumlocution is not explained, but other sources make it clear the writers are talking about too much and the “wrong” kind of sex:

We last week made some observations on the supposed influence of excessive mental work upon the health of the brain, and particularly as to the share which it really takes in the causation of insomnia. We showed that that influence was far more imaginary than real; or rather, that people who do break down from over brain-work are, in all but a small percentage of cases, found to have been simultaneously committing other, and even more serious, sins against the laws of health. We now wish to say a few words about what is a far more common cause of nervous breakdown than is the mere excess of work-namely, worry. Not long since we stated this view of the case in commenting upon an article in The Times which also adopted it; and our remarks attracted a good deal of attention from our contemporaries. One obvious difficulty seemed to strike a good many of our lay friends. We were asked from all sides if this were not a miserably despairing doctrine that we were teaching; whether, if it be true that the cares and troubles of life are more fatal to nervous health than excessive labour, it is not pretty certain that nervous diseases must increase enormously with the increasing rush and competition of modern society.

On 5 June 1874, Edward L. Youmans, the founder and editor of Popular Science, gave a lecture on Herbert Spencer’s contribution to the theory of evolution in which he noted that Spencer suffered a nervous breakdown from overwork:

Mr. Spencer proposed to the editor of the Westminster Review to write an article upon the subject under the title of “The Cause of all Progress,” which was objected to as being too assuming. The article was, however, at that time agreed upon, with the understanding that it should be written as soon as the “Principles of Psychology” was finished. The agreement was doomed to be defeated, however, so far as the date was concerned, for, along with the completion of the “Psychology,” in July, 1855, there came a nervous breakdown, which incapacitated Mr. Spencer for labor during a period of eighteen months—the whole work having been written in less than a year.

That same year nervous breakdown appears in John Spender’s Therapeutic Means for the Relief of Pain, but it appears in quotation marks, indicating that the term was unfamiliar to at least some medical professionals:

The careful regulation of a rich nutritive diet, with the administration of Phosphorous and cod-liver oil, brought about a complete alleviation of pain, and the health improved in all respects. Dr. Broadbent has given the medicine also in cases of “nervous breakdown” and atonic dyspepsia.

The use of phosphorous in treating nervous breakdowns mentioned by Spender would again be mentioned in a medical text by Thomas Mays and an article in the journal New Medicines from 1878. (Needless to say, my including these quotations is not a recommendation for treatment. One should not take medical advice from a word origins website, much less medical advice from the nineteenth century.)

And in his 1880 Brain-Work and Overwork, H. C. Wood engages in a rather amazing string of euphemisms for sex, which he says can cause nervous breakdowns, especially when it is “secret vice” or “matrimonial excess”:

Secret vice, although its results have been greatly exaggerated, is capable of producing, and does produce, much serious disease. Its practice is by no means confined to males, and is very often persisted in rather through ignorance than through want of virtue. There comes, therefore, in the life of the youth of both sexes, a time when it is the duty of the appropriate parent to explain fully and modestly the relations of the sexes. In regard to girls. Nature points out the appropriate age, and the explanation should immediately follow the first evidences of sexual development. In regard to boys, individual needs and circumstances differ, but about the twelfth or fourteenth year would seem proper. Always the parent should remember that innocence is not virtue, but ignorance; and that it is a very poor foundation upon which to rest in the temptation that comes, especially in our large cities, to every one.

In a considerable proportion of the cases of nervous breakdown which have come under my notice, the disorder has had its origin in matrimonial excesses. Intemperance in this regard rests as often in ignorance as in lack of self-control. Whether indulged in through want of knowledge or want of virtue, excess always brings the penalty in the shape of weariness, lassitude, loss of power to do mental work, and gradual impairment of nerve-force, which may progress until the man or woman is reduced to a condition of hysterical exhaustion. Sometimes excess seems for a long time to bear no evil fruits, until suddenly a serious organic nervous affection is developed. The danger from this source is especially real to brain-workers, as the robust man, who leads a life of activity in the open air, is far more able to resist. The important point as to where the line is to be drawn between proper and improper indulgence must be settled by each individual for himself, with or without the aid of his physician.

The earliest citation for nervous breakdown in the Oxford English Dictionary is from December 1884 (which the OED misdates as 1870 in that it cites a reprint of the story rather than the original). From Walter Besant’s short story Even with This:

Next morning, I was not surprised to receive a note from Isabel. She said that her husband was suddenly prostrated with some kind of nervous breakdown, though he looked very well, and that the doctor ordered him to give up all work, break off all engagements, and go away for three months at least. They were going the same day.

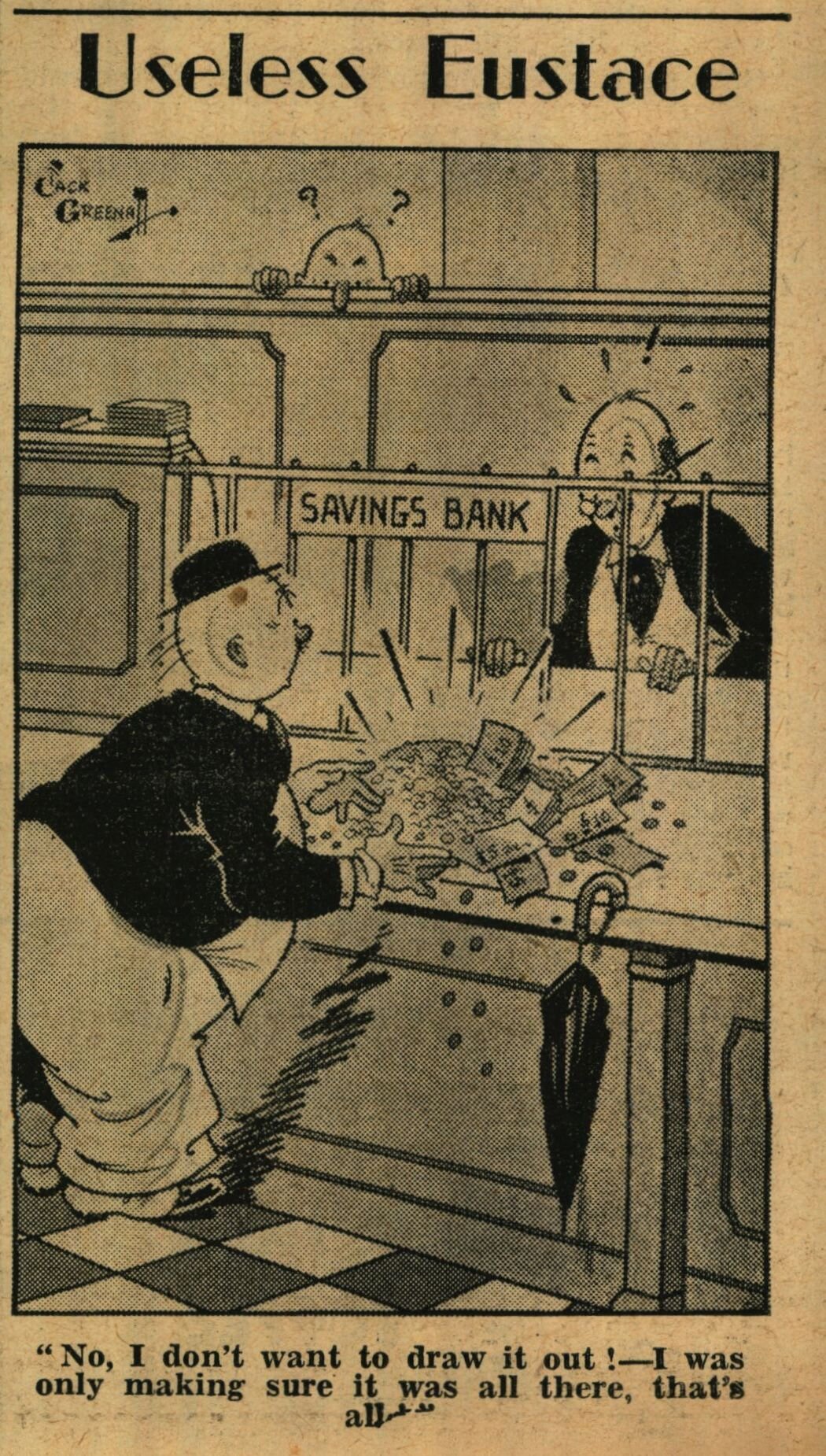

The connection between sex and nervous breakdowns also appears in an 1889 short story by Anton Chekhov, Припадок (Pripadok), which literally means seizure but is usually translated as Nervous Breakdown. In the story, the protagonist, a student named Vasilyev, visits the Moscow red light district with friends. Overwhelmed by shame and disgust of what he witnesses there, he has a breakdown.

Needless to say, the idea that sex, of any kind or amount, can lead to a nervous breakdown is no longer considered valid, although feelings of guilt and shame could conceivably contribute to stress generally.

Sources:

Besant, Walter. “Even with This.” Longman’s Magazine, December 1884, 73. ProQuest Historical Periodicals.

Hall-Flavin, Daniel K. “Nervous Breakdown: What Does It Mean?” Mayoclinic.org, 26 October 2016.

Mays, Thomas J. On the Therapeutic Forces. Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston, 1878, 58. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

“Medical Annotations: Insomnia from ‘Worry.’” The Lancet, 11 January 1873. 63. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, September 2003, s.v. nervous, adj. and n.

“Phosphorized Cod Liver Oil.” New Medicines, 1.5, August 1878, 140. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Spender, John Kent. Therapeutic Means for the Relief of Pain. London: Macmillan, 1874, 107. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

“To Correspondents.” The Herald of Health and Journal of Physical Culture, 7.3, March 1866, 105. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Useem, Jerry. “Bring Back the Nervous Breakdown.” The Atlantic, March 2021. (Note: I cite this article because it brought the term nervous breakdown to my attention, but the article gets the origin of the term wrong, dating it to only 1901.)

Wood, H. C. Brain-Work and Overwork. Philadelphia: Presley Blakiston, 1880, 43–44. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Youmans, Edward L. “Herbert Spencer” (5 June 1874). The World (New York), 6 June 1874, 2. NewsBank: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Image credit: Alexander Mogilevsky, 1954. Fair use of a low-resolution copy of a copyrighted image to illustrate a point under discussion.

Thanks to LanguageHat for verifying the meaning of Припадок.