19 May 2021

An absentee is someone who is not present when they are supposed to be. It is an example of semantic generalization, a word that at first refers to a specific thing but over time comes to refer to a wider category of things. In this case, absentee originally referred to English owners of land in Ireland who seldom or never visited their Irish estates, but eventually the word came to refer to anyone who wasn’t at a place when they were supposed to have been.

Absentee comes from the verb absent + -ee. The English verb to absent, meaning to withdraw or remove oneself, dates to the late fourteenth or early fifteenth centuries. It is a borrowing of the Anglo-Norman verb absenter, to stay away from, a verb that is recorded in the late thirteenth century and which comes from the Latin absentare. The -ee suffix, originally used in legal terms but which has since expanded into other contexts, marks nouns used as indirect objects. It is from the Anglo-Norman -é.

Absentee first appears in English in the Act of Absenties (28.H8), passed by the Irish parliament in 1537 during the reign of Henry VIII. The intent of the act was to seize revenues from absentee landlords in Ireland, ostensibly for the benefit of the Irish people and the security of English rule in Ireland, because of the failures of the absentee landlords to maintain their estates. But it was passed contemporaneously with Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries in England, part of a larger scheme to raise money for the crown. This passage quoted below is from the beginning of the act and contains part of one of the longest sentences I have ever seen, extending over two pages (the initial sentence of the act ends just before the word, “Be it enacted”):

The Act of Absenties.

For asmuch as it is notorious and manifest that this the Kings land of Ireland being inhabited and in due obedience and subiection unto the Kings most noble progenitors kings of England, who in those dayes in the right of the Crowne of England, had great possessions, rents, and profites within the same land, hath principally growen into ruine, dessolation. rebellion and decay, by occasion that great dominions, landes, and possessions within the same land, as well by the kings graunts as by course of inheritance, and otherwise desceded to Noblemen of the Realme of England, and especially the lands and dominions of the Earledomes in Ulster and Leinster, who hauing the same both they and their heyres by processe of time demoring within the said realme of England, and not prouiding for the good order and suertie of the same their possessions there, in their absence and by their negligences suffered those of the wilde Irishrie being mortall and naturall enemies of the kings of England, and English dominion, to enter and hold the same without resistance, [...] and that if his Grace would take of the inheritors and possessioners of the same, the arrerages of the two parts of the yearely profites thereof by reason of their absence out of the said land, contrary to ye statuts therof prouided, the same would counteruaile the purchase therof, yet for corroboration of the right and title of our said soueraigne Lord the King, and his heires, which he hath to all the same lands, dominions and possessions. Be it enacted, established, and ordeyned by the king our soueraigns Lord, Lords spirituall and temporall, and commons in this present Parliament assembled, and by authoritie of the same, that King, his heyres and assignes shall haue, hold, and enioy as in the right of the Crowne of England, all honors, mannors, castles, seigniories, hundreds, franchises, liberties, countie palantines, iurisdictions, anuities, knights fees, aduowsons, patronages, lands tenements, wood, meadowes [...]

Thomas Blount’s legal dictionary of 1670 defines absentee, notes its French origin, and references the 1537 act:

Absentees or des Absentees, was a Parliament so called, held at Dublin, 10 May, 28 H.8.

The 1537 act hardly ended, or even curtailed, the practice of absentee landlordism, and the abuses the Irish people suffered under neglect of their absent landlords and the money continually siphoned out of Ireland became one of leading causes of Irish rebellion over the centuries.

In the eighteenth century, Jonathan Swift wrote, under the pseudonym of M. B. Drapier, of the practice in one of series of pamphlets attacking the practices of English governance in Ireland. “An Humble Address to Both Houses of Parliament” (Drapier Letter 7) is primarily in opposition to a patent to mint coins granted to William Wood, but mentions the problem of absentee landlords shipping their profits over the Irish Sea to England. The pamphlet was written c.1725 but went initially unpublished because the patent had been withdrawn. It was finally published ten years later in a collection of Swift’s works:

The Rents of Land in Ireland, since they have been of late so enormously raised and screwed up, may be computed to about two Millions; whereof one third Part, at least, is directly transmitted to those, who are perpetual Absentees in England, as I find by a Computation made with the Assistance of several skillful Gentlemen.

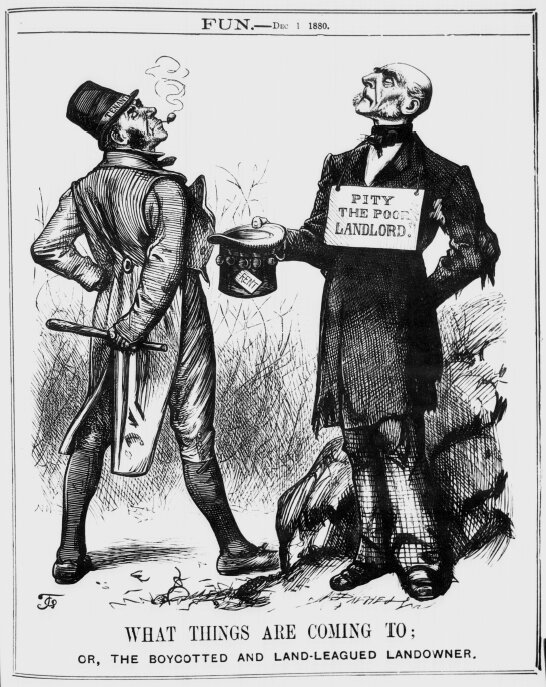

Nor is absentee the only word to arise out of the practice of absentee landlordism in Ireland. The term boycott also arose out of the practice.

But also in the eighteenth century, the meaning of absentee expanded to include people other than English landlords who weren’t in Ireland. In his 1792 memoirs, Unitarian and dissenting writer Gilbert Wakefield wrote of the practice of beneficed clergy hiring others to do their work for them in the pulpit:

The common exhibitioners at St. Mary’s, were the hack preachers, employed in the service of defaulters and absentees. A piteous unedifying tribe!

And by the early nineteenth century, absentee was being used to denote students who played hooky. From Joseph Lancaster’s 1805 edition of his Improvements in Education:

The monitor calls his boys to muster—the class go out of the seats in due order—go round the school-room; and, in going, each boy stops, and ranges himself against the wall, under that number which belongs to his name in the class-list. By this means the absentees are pointed out at once—every boy who is absent will leave a number vacant.

The use of absentee in the context of voting started during the U.S. Civil War, allowing for soldiers stationed away from home to vote. The following is from a speech given by William Warner, a member of the Michigan state legislature, to that body on 28 January 1864:

The House bill No. 5 provides, that polls shall be opened for each regiment, or detached portion of each regiment or company of Michigan soldiers, when absent from the township or ward in which they reside, in the military service of this State or of the United States; that such polls shall be opened on the same day that is provided for by Title 83, Chap. 6, of the compiled laws; that Commissioners shall be appointed to take the votes of such absentees; that the votes shall be canvassed immediately after the polls shall be closed.

A rather long path from sixteenth-century Ireland to the U.S. Civil War.

Sources:

Anglo-Norman Dictionary, 2007, s.v. absenter.

Blount, Thomas. ΝΟΜΟ-ΛΕΞΙΚΟΝ: A Law Dictionary. London: Thomas Newcomb for John Martin and Henry Herringman, 1670. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Lancaster, Joseph. Improvements in Education, third edition. London: Darton and Harvey, 1805, 112. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, December 2020, s.v. absentee, n. and adj., absent, v.

The Statutes of Ireland, Beginning the Third Yere of K. Edward the Second, and Continuing Until the End of the Parliament, Begunne in the Eleventh Yeare of the Reign of Our Most Gracious Soveraigne Lord King James. Dublin: Society of Stationers, 1621, 95–100. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Swift, Jonathan (under the pseudonym of M. B. Drapier). “An Humble Address to Both Houses of Parliament” (Drapier Letter 7) (c.1725). Works, vol. 4. Dublin: George Faulkner, 1735, 223. Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO).

Wakefield, Gilbert. Memoirs of the Life of Gilbert Wakefield. London: E. Hodson, 1792, 97. Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO).

Warner, William. Soldier’s Suffrage. Detroit: 1864, 5. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Image credit: Thomson, John Gordon. “What Things Are Coming to; or, the Boycotted and Land-Leagued Landowner.” Fun, 32.812, 1 December 1880, 217. ProQuest Historical Periodicals. Public domain image.