28 January 2022

Normality, normalcy, and normalness all carry the same meaning, that of conformance to a standard or to the usual state of things. But while they mean the same thing, the three words differ in register, dialect, and frequency of use. Of the three, normality is the most common on both sides of the Atlantic, but normalcy is more likely to be found in North America than in Britain and is viewed by some as an error or, at least, as an informal usage. Normalcy is also historically associated with the 1920 presidential candidacy of Warren Harding. Normalness is quite rare on both sides of the Atlantic.

Etymologically, the three words are similar. They share the same root, normal, but use different endings that change nouns and adjectives into abstract nouns, -ity, -cy, and -ness. And all three first appear in the mid nineteenth century.

Of the three, normality is the oldest and the most common. It is most likely modeled on the French normalité, which dates to 1834 in that language. The English word appears shortly after the French one, in an article about German literature in the May 1837 Eclectic Review:

The German possesses little social flexibility, yet so much stronger is his individuality, and to that he will give free expression, even to willfulness and caricature. Genius bursts through every barrier that would oppose it; and even amongst the vulgar, the mother-wit breaks out. When one contemplates the literature of other nations, one observes more or less of normality—a sort of French art of gardening; it is the German alone which is forest-like—a field overrun with wild growth. Each intellect is a flower, distinct in form, colour, perfume.

Normalcy appears a couple of decades later, but its early use is restricted to mathematical jargon. From Charles Davies’s and William Peck’s 1855 Mathematical Dictionary:

SUB-NOR´MAL. [L. sub, and norma, a rule]. That part of the axis on which the normal is taken, contained between the foot of the ordinate through the point of normalcy of the curve, and the point in which the normal intersects the axis.

A review of Joseph Worcester’s 1860 dictionary in the May 1860 issue of the New Englander notes that normalcy could be found in technical texts but had yet to appear in any general dictionary. (Worcester was the chief competitor to Noah Webster in the nineteenth century American dictionary market.)

The 1864 edition of Webster’s dictionary (published posthumously) corrected this omission, but the definition does not make clear if it is used generally or only in the mathematical sense:

Nôr´mal, a. (Lat. normalis, from norma, rule, pattern; Fr. & Sp. normal, It. normale.)

1. According to an established norm, rule, or principle; conformed to a type or regular form; accomplishing the end or destiny; performing the proper functions; not abnormal; regular; analogical.

[...]

2. (Geom.) According to a square or rule; perpendicular; forming a right angle.

[...]Nôr´mal, n. (Fr. ligne normale. See supra.)

1. A perpendicular.

2. (Geom.) A straight line perpendicular to the tangent of a curve at any point, and included between the curve and the access of the abscissus.

[...]Nôr´mal-cy, n. The state or fact of being normal; as, the point of normalcy. [Rare.]

But the general (i.e., non-mathematical) sense is definitely in use a decade later. From the Chicago Sunday Times of 14 February 1875 in an article about aristocrats at Parisian dances:

Stiffness and pretense soon wear off at the balls. Blood, not a bit blue, asserts itself, and animal spirits seek their wonted channel. If their claim to high breeding be accepted, they will at once forego further self-assertion. A little wine warms them into candor and normalcy, and then grand airs fly off like a covey of partridges, not to return, at least the same evening.

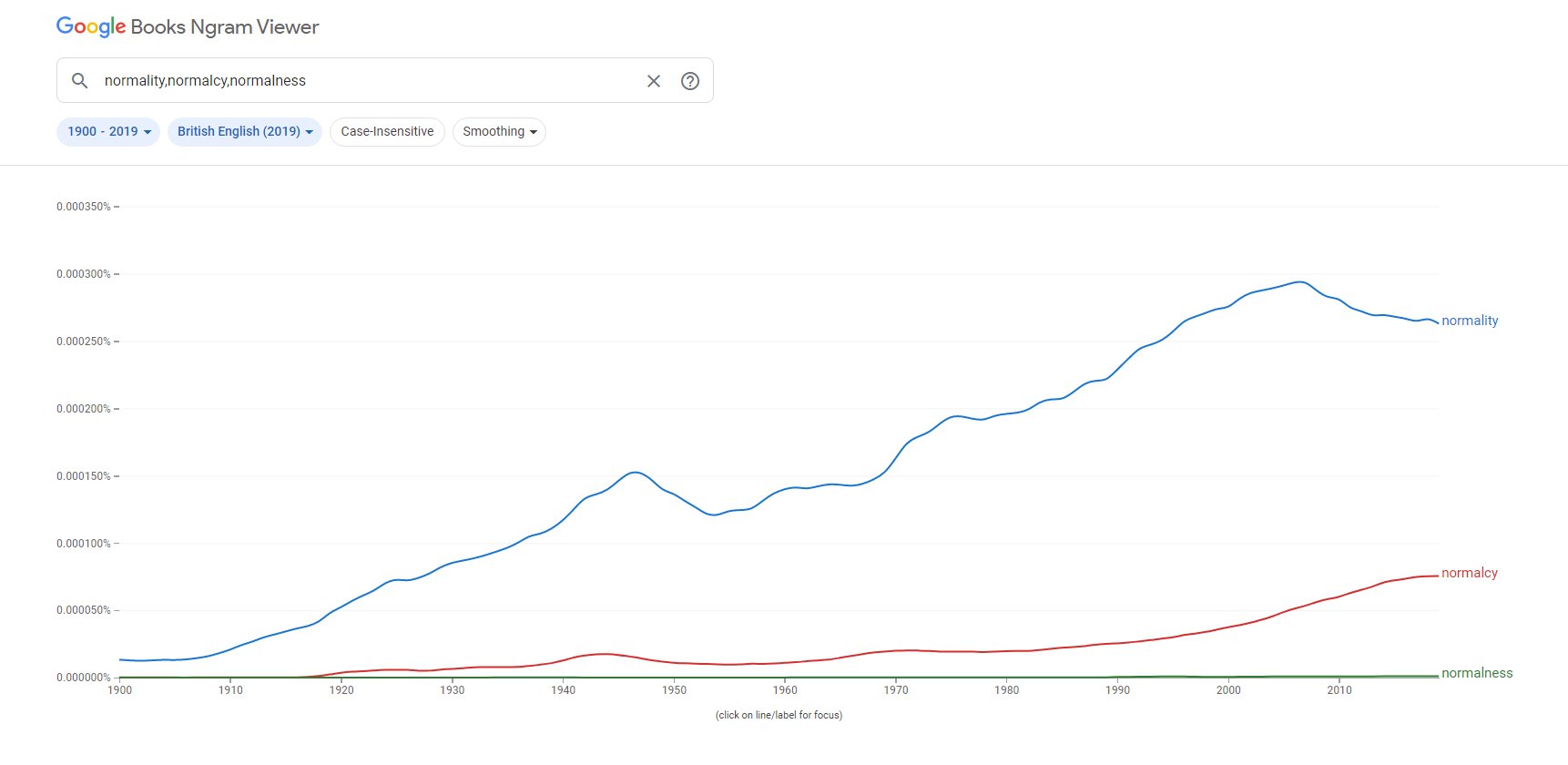

But as the Google Ngram graph shows, normalcy remained rare until around 1916 when it surged in popularity in American writing. (The Google Ngram tool is not the best measure, but it makes a quick “back of the envelope” estimate that is usually reasonably accurate. Plus, the tool makes it easy to create comparative visualizations, which is why I use it here.) In 1920, Republican U.S. presidential candidate Warren Harding made Return to Normalcy his campaign slogan. The slogan was widely critiqued as “bad” English, but it capitalized on the weariness created by the First World War, the influenza pandemic, and the anti-Communist Red Scare, and Harding won in a landslide. Harding was using normalcy in his speeches as early as 14 June 1920, as this transcript in the Kansas City Star shows:

Normal thinking will help more. The world does deeply need to get normal, and liberal doses of mental science freely mixed with resolution will help mightily. I do not mean the old order will be restored. It will never be again. But there is a sane normalcy due under the new conditions, to be reached in deliberation and understanding. And all men must understand and join in reaching it. Certain fundamentals are unchangeable and everlasting.

But as we have seen, Harding did not coin this sense of normalcy, nor did his use significantly alter the popular trajectory of the phrase, as can be seen in the Google Ngram graph. Rather, Harding’s use of the phrase started after the surge in popularity was well underway and well before it had reached its initial peak, which was around 1924. So, he didn’t make a significant contribution to the popularity of the word. What Harding’s use of normalcy did, however, was bring the word to the attention of grammarians and linguists.

That leaves us with normalness, which is the red-headed stepchild of the three. It has always remained rare in both British and American English. But it appeared at about the same time as the other two words. Its first appearance is in an 1854 translation of Ludwig Feuerbach’s The Essence of Christianity. Of note is the translator, Mary Ann Evans, better known by the pseudonym she used in penning literary works, George Eliot:

Let the fanatic make disciples as the sand on the sea-shore; the sand is still sand; mine be the pearl—a júdicious friend. The agreement of others is therefore my criterion of the normalness, the universality, the truth of my thoughts. I cannot so abstract myself from myself as to judge myself with perfect freedom and disinterestedness; but another has an impartial judgment; through him I correct, complete, extend my own judgment, my own taste, my own knowledge.

Feuerbach’s German was Normalität.

Sources:

“Article VI.—Worcester’s Dictionary.” New Englander (New Haven, Connecticut), May 1860, 417. ProQuest.

“Art. VII. Menzel on German Literature.” The Eclectic Review (London), May 1837, 504. ProQuest Historical Periodicals.

“Dancing Paris” (24 January 1875). Sunday Times (Chicago), 14 February 1875, 12. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Davies, Charles and William G. Peck. Mathematical Dictionary and Cyclopedia of Mathematical Science. New York: A.S. Barnes, 1855, 542. Nineteenth Century Collections Online.

Dr. Webster’s Complete Dictionary of the English Language. Chauncey Goodrich and Noel Porter, eds. London: Bell and Daldy, et al., 1864, 893, s.v. normalcy, n. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Feuerbach, Ludwig. The Essence of Christianity. Mary Ann Evans, trans. London: John Chapman, 1854, 157. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary of English Usage. Springfield, Massachusetts: Merriam-Webster, 1994, 664–65, s.v. normalcy.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, December 2003, modified March 2021, s.v. normality, n.; modified June 2019, s.v. normalcy, n.; modified March 2018, s.v. normalness, n.

“Where Harding Has Stood.” Kansas City Star (Missouri), 14 June 1920, 1. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Image credit: Google Books Ngram Viewer, accessed 11 December 2021.