29 May 2023

Round robin is a term that has had many meanings over the centuries. Today, one perhaps hears it most often as a term for a sports tournament in which each contestant plays at least one match with all of the others. But this is a relatively recent sense of the term.

I’m not going to detail all the various senses—that would be the topic for a short book. But over the years round robin has been used as a disparaging term for the eucharistic host (16th C); a disparaging term for a man (16th C); a small ruff or collar (17th C); various round objects, such as leather loops or pancakes (18th C); any of a variety of fishes or plants (18th C); an Australian term for a burglar’s tool (19th C); a British term for a swindle (19th C); a chain letter (19th C); and an American slang verb meaning to have sex with multiple partners in succession (1960)

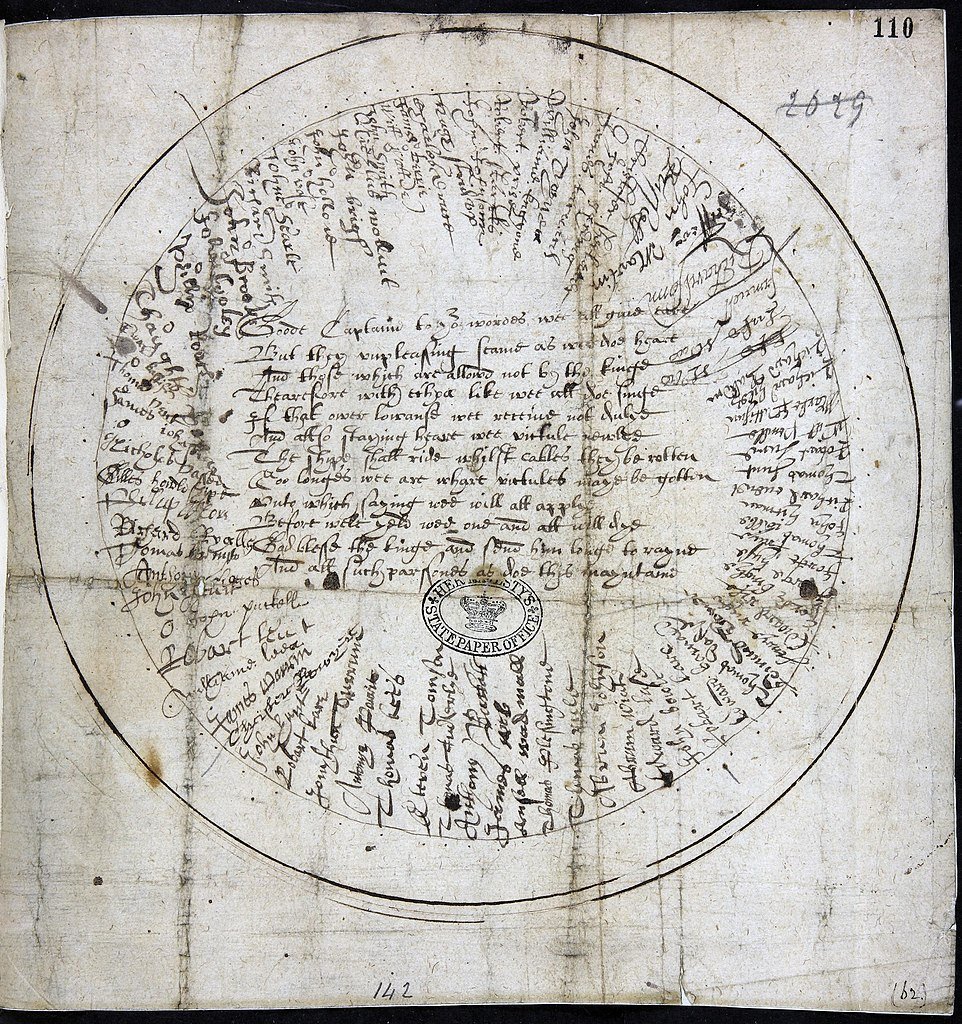

But the sports term is an extension of a nautical sense dating to late seventeenth century where it is used to denote a petition or complaint with the signatures arranged in a circle to hide who had signed first, who would presumably be the ringleader (Note, this is not the origin of the term ringleader, which dates to almost two hundred years earlier).

The photo is of round-robin letter found in the Calendar of State Papers for 1627 and addressed to a captain in King Charles I’s fleet. The letter is signed by seventy-six sailors, with the signatures arranged around twelve lines of verse that state they will not weigh anchor until they are paid and the ship is fully victualed. The lines read:

Goode Captaine to your wordes wee all give eare

But they unpleasing seame as wee doe heare

And those which are allowed not by the kinge

Thearefore with echoa like wee all doe sing

If that ower [al]lowanse wee receive not dulye

And also staying heare wee victule newlye

The shipe shall ride whilst cables they be rotten

Andso longes wee are whare victules maye be gotten

Unto which saying wee will all apply

Before wele yeld wee one and all will dye

God blesse the kinge and send him longe to rayne

And all such parsons as doe this mayntaine

(Good Captain, to your words we all give ear

but they unpleasing seem as we do hear

and those which are allowed not by the king

therefore with echo-like we all do sing

if that our allowance we receive not duly

and also staying here we victual newly

the ship shall ride whilst cables they be rotten

and so long as we are where victuals may be gotten

until which saying will we all apply

before we yield we one and all will die

God bless the king and send him long to reign

and all such persons as do this maintain.)

As the photo demonstrates, this practice of round-robin letters dates to c.1627 at least, but the term round robin in reference to the practice doesn’t appear until the end of the seventeenth century. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) has a citation of this sense from 1698 in a manuscript with the abbreviated title and shelfmark of High Court of Admiralty Exam. & Answers (P.R.O.: HCA 13/81) f. 679v:

Some of them drew up a paper commonly called a Round Robin, and signed the same whereby they intimated that if the Captaine would not give them leave to goe a shore, they would take leave.

This sense of the term is elaborated on in Charles Johnson’s 1724 A General History of the Pyrates:

This being approved of, it was unanimously resolved on, and the underwritten Petition drawn up and signed by the whole Company in the Manner of what they call a Round Robin, that is, the Names were writ in a Circle, to avoid all Appearance of Pre-eminence, and least any Person should be mark’d out by the Government, as a principal Rogue among them.

By the mid seventeenth century this usage had moved from nautical to general use. An anonymous 16 October 1755 piece in the newspaper The World uses it in a non-nautical context, although the article does make use of nautical imagery. The OED credits the piece to Philip Stanhope, Fourth Earl of Chesterfield; Stanhope did pen pieces for the paper, but I don’t know what evidence the dictionary uses for this particular credit—the writer Adam Fitz-Adam is the publisher and primary writer for that paper and is another logical candidate for authorship. The piece is an over-the-top screed against women wearing make-up, which I can only hope was written at least half in jest:

As my fair fellow subjects were always famous for their public spirit and love of their country, I hope they will upon the present emergency of the war with France, distinguish themselves by unequivocal proofs of patriotism. I flatter myself that they will at their first appearance in town, publicly renounce those French fashions, which of late years have brought their principles, both with regard to religion and government, a little in question. And therefore I exhort them to disband their curls, comb their heads, wear white linen, and clean pocket handkerchiefs, in open defiance of all the power of France. But above all, I insist upon their laying aside that shameful piratical practice of hoisting false colours upon their top-gallant, in the mistaken notion of captivating and enslaving their countrymen. This may the more easily do at first, since it is to be presumed, that during their retirement, their faces have enjoyed uninterrupted rest. Mercury and vermillion have made depredations these six months; good air and good hours may perhaps have restored, to a certain degree at least, their natural carnation: but at worst, I will venture to assure them, that such of their lovers who may know them again in that state of native artless beauty, will rejoice to find the communication opened again, and all the barriers of plaister and stucco removed. Be it known to them, that there is not a man in England, who does not infinitely prefer the brownest natural, to the whitest artificial skin; and I have received numberless letters from men of the first fashion, not only requesting, but requiring me to proclaim this truth, with leave to publish their names; which however I decline; but if I thought it could be of any use, I could easily present them with a round robin to that effect, of above a thousand of the most respectable names.

The sporting sense is an extension of the idea of equality among the participants, where no one artificially ranked above another. The term arises in tennis and dates to the closing years of the nineteenth century, and it appears at about the same time as seed https://www.wordorigins.org/big-list-entries/seed begins to be used as a term for ranking players in a tournament. A round-robin tournament is the antithesis of a seeded one. From an article about the planning for a tennis tournament that appeared in the New York Times of 28 September 1894

Many improvements for next year’s Newport championship have been suggested by those who are vainly striving to adjust the varying chances of the game so as to do away with the element of luck altogether. Juggling the drawings so that the stronger players appear at regular intervals on the score board appear to be most favored, as no change in the general arrangements is needed. Then a well-known player has proposed that the four players who reach the semi-finals play a kind of “round robin” tournament. This is also a good suggestion and would involve playing only three more matches than the old way.

And there is this from the 30 May 1895 New-York Tribune:

In order to prevent flukes, a round robin tournament will be played, each player contesting one match with each of his competitors.

And from this base in the world of tennis, the term spread to other sports.

Discuss this post