25 August 2025

[Edit 26 August 2025: corrected error about the fate of Romulus Augustulus}

The Middle Ages, or medieval period, runs from roughly 500–1500 C. E., that is more or less from the so-called fall of Rome to the so-called Renaissance and the start of the modern era. While Middle Ages is a pretty obvious term for a period between two others, there are a lot of problems with dividing history into this era.

First, the Middle Ages is a Western Eurocentric periodization. The history of any other region cannot be neatly divided by these events.

Second, the “fall of Rome” is something of a myth. It is true that Rome was sacked numerous times in the fifth century and the last person formally claiming the title of emperor of the Western Roman Empire was deposed in 476, but the people of the empire did not suddenly stop thinking of themselves as Roman, and Roman emperors continued to rule from Constantinople well into the fifteenth century. The people we commonly label as Byzantine today thought of themselves as Roman.

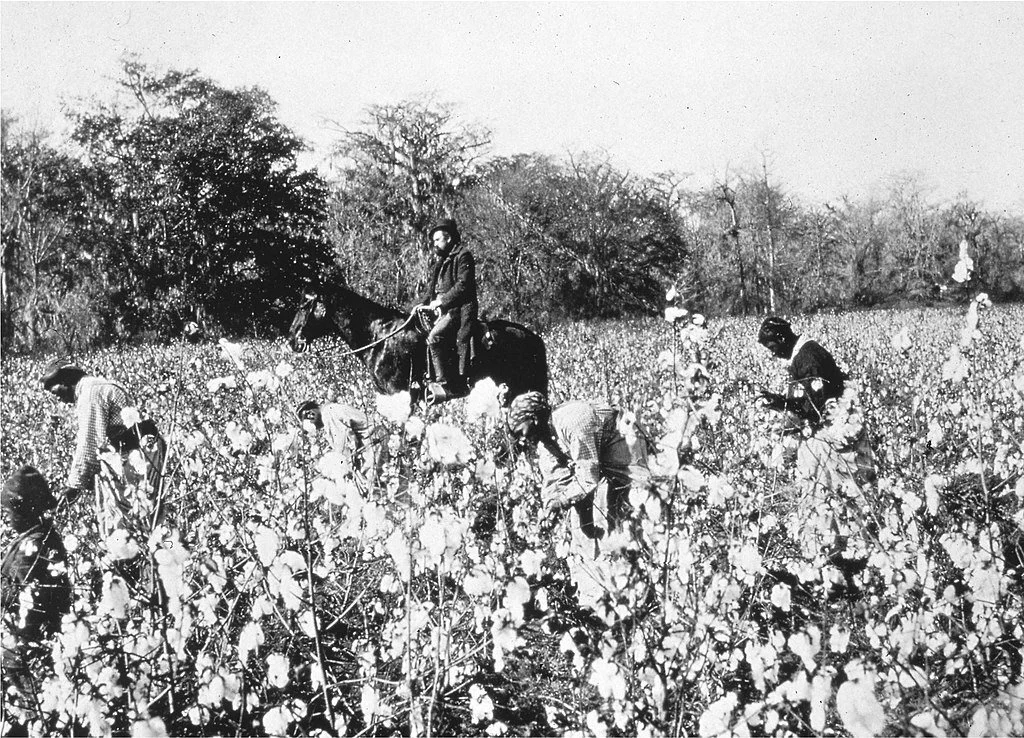

Third, while there was indeed a great flowering of art and learning in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Italy, this was by no means unprecedented or unique. There were lots of “renaissances,” so many that such flowerings and “rediscoveries” of ancient works really need to be viewed as a fact of any age, not a singular event belonging to one time and place. To cite just one example, the “pre-Renaissance” image above is taken from a copy of Nicole Oresme’s fourteenth-century translation of Aristotle, done in Paris.

Finally, Middle Ages and medieval are terms imposed upon the era by later peoples. The people of the era didn’t call themselves medieval or say they were living in the Middle Ages. Towards the end of the period, they would have called themselves modern, a word that is in use by 1456 in English and a century earlier in French. So when did Middle Ages and medieval come into use?

The term Middle Ages first appears in John Foxe’s 1570 edition of his Protestant martyrology, Actes and Monumentes:

Thus thou seest (gentle reader) sufficiently declared, what the Moonkes were in the primitiue tyme of the church, and what were the Moonkes of the middle age, and of these our latter dayes of the church.

It appears again in 1605 in William Camden’s “Certaine Poems,” a section of his Remaines of a Greater Worke, in which he gives samples of medieval poetry:

I will onely giue you a taste of some of midle age, which was so ouercast with darke clouds, or rather thicke fogges of ignorance, that euery little sparke of liberall learning seemed wonderfull.

Camden is already describing the period as dark and ignorant, an intellectual and social abyss between the lights of Rome and the Renaissance, an inaccurate description that present-day scholars of the period take great pains to try to eradicate (Cf. dark ages).

Medieval is a much later term, with its first known appearance in the preface to Thomas Fosbroke’s 1817 edition of his British Monachism: Or, Manners and Customs of the Monks and Nuns of England:

He professes to illustrate mediæval customs upon mediæval principles, from a persuasion, that contemporary ideas are requisite to the accurate elucidation of history.

Medieval is an alteration of the modern Latin phrase medium ævum (middle ages), which dates to 1604. The word may be modeled after the earlier primeval.

Finally, the phrase to get medieval, meaning to torture someone or otherwise become violent or aggressive, dates to Quentin Tarantino’s 1994 movie Pulp Fiction, in which the character Marsellus Wallace, played by Ving Rhames, says:

What now? Well let me tell you what now. I’m gonna call a couple pipe-hittin' n[——]rs, who'll go to work on homes here with a pair of pliers and a blow torch. Hear me talkin' hillbilly boy?! I ain’t through with you by a damn sight. I’m gonna git medieval on your ass.

Which brings us to another myth about the medieval era, that it was an era characterized by brutality and torture. Like any age, it had its violence, but it was not especially violent in comparison with other periods. For instance, the twentieth century, with its world wars, was far more violent than any century of the medieval era. And most of the artifacts and stories one encounters in “medieval torture” museum exhibits actually date to the Early Modern era and the Protestant Reformation, not the Middle Ages.

Sources:

Camden, William. “Certaine Poems.” In Remaines of a Greater Worke. London: George Eld for Simon Waterson, 1605, 2. ProQuest: Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Fosbrooke, Thomas Dudley. British Monachism. London: John Nicols, Son, and Bentley, 1817, 14. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Foxe, John. The First Volume of the Ecclesiasticall History Contayning the Actes and Monumentes of Thynges Passed. London: John Daye, 1570, 204/1. ProQuest: Early English Books Online.

Oxford English Dictionary Online, March 2002, s.v. middle age, n. & adj.; June 2001, s.v. medieval, adj. & n.

Tarantino, Quentin and Roger Avary (writers). Pulp Fiction (film). Miramax, 1994. Dailyscript.com.

Image credit: Anonymous, fifteenth century. Rouen, Bibliothèque Municipale, Ms. 927, fol. 145. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain image.